MFA Tells Ongoing Story of Japan with Two New Exhibits

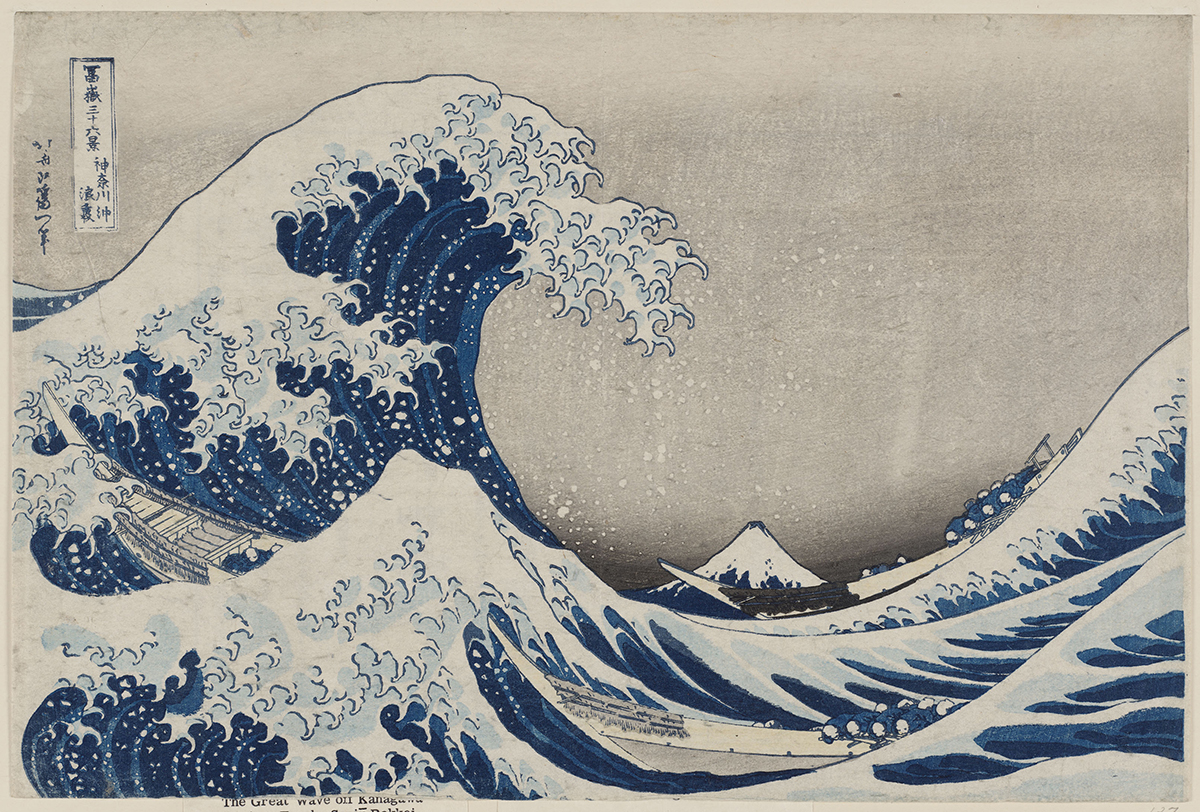

“Under the Wave off Kanagawa” / Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Inside the Ann and Graham Gund Gallery at the Museum of Fine Arts, a giant wave threatens to overtake a trio of fishing boats, while a tiny Mt. Fuji looms in the distance. But the boats—and the people in them—remain untouched, frozen in time inside a woodblock print strikingly smaller in reality than expectation, captured by an artist nearly 200 years ago.

Meanwhile, in the Henry and Lois Foster Gallery, video footage shows a series of waves that succeed at destruction, stretching as far as six miles, reaching more than ten stories high, and killing thousands in their wake.

Both the print and the video footage, featured separately in two new exhibits opening on April 5, embody an effort by MFA curators to tell not only the history, but also the ongoing story of Japan.

“Under the Wave off Kanagawa,” the famous woodblock print that remains an icon of Japanese art two centuries after its creation, is one of more than 230 works featured in “Hokusai,” a retrospective of the painter Katsushika Hokusai put together by Sarah Thompson, assistant curator of Japanese prints. The video footage, on the other hand, set in modern times, complements 17 photographers’ responses to the “triple disaster” that struck Japan in March 2011, collected by Anne Havinga, senior curator of photographs, and Anne Nishimura Morse, senior curator of Japanese art, for “In the Wake.”

“Hokusai”

On view April 5-August 9, curated by Sarah Thompson.

Since the 19th century, the MFA has been at the forefront of showcasing Japanese art in the U.S. In 1890, it became the first American museum to establish a Japanese collection and to appoint a curator specializing in Japanese art. In 1892, “Hokusai and His School,” mounted at the MFA, became the first scholarly presentation of Japanese art in the country.

Today, in celebration of the Asian art department’s 125th anniversary, the MFA presents “Hokusai,” a more comprehensive reprise of the 1892 exhibit.

The seven color-coded sections of “Hokusai,” divided up thematically rather than chronologically, present a lifetime of work from an artist who continued to produce quality—and arguably some of his best—work well into his 80s. “Under the Wave off Kanagawa,” in fact, was painted when Hokusai was 70. At the MFA, it hangs alongside 35 other varying views of Mt. Fuji—the first time the series has been displayed together at the museum.

In addition to prints and paintings, the exhibit features a variety of objects, including lanterns, fans, and illustrated books. Cutout dioramas, designed by Hokusai, both hang on the wall in their original, two-dimensional format, and stand in glass cases, recreated into three-dimensional models by MFA senior designer Tomomi Itakura. Intended to serve as paper toys for children, they epitomize the everyday, household nature of much of Hokusai’s work. While the artist did produce a number of high-quality private commissions, most of his prints cost about as much as a large bowl of noodle soup at the time, notes Thompson, easily accessible for the general population.

Detail of Hokusai’s “Phoenix,” a multi-panel screen painting from 1835. (Photo by Olga Khvan)

“In the Wake: Japanese Photographers Respond to 3/11”

On view April 5-July 12, co-curated by Anne Havinga and Anne Nishimura Morse.

At 2:46 p.m. on March 11, 2011, an earthquake rattled the northeast coast of Japan—the most powerful earthquake to hit the country in recorded history. It triggered a tsunami, whose waves submerged more than 200 square miles of land over the next hour or so. A few days later, the Fukushima nuclear power plant, which had been flooded by the tsunami, began to fail, releasing high amounts of radioactive material into the air. In Japan, the events have collectively come to be known as “3/11” or the “triple disaster.”

There were, of course, the photojournalists and videographers that began documenting the catastrophe as soon as the warning alarms sounded. “It was one of those disasters that was captured in real time,” says Morse, who along with Havinga felt that it was important to include live footage in the exhibit. “It gives you some sense of the speed of it all, the massive destruction, the chaos that happens.”

But the majority of the exhibit focuses on the response elicited in the disaster’s aftermath, expressed through photography. Nayo Hatakeyama, who lost his mother and his ancestral home in the tsunami, for example, took to documenting the slow process of reconstruction in his hometown, reflecting the passage of time. Six prints by Nobuyoshi Araki bear jagged marks—the negatives had been gouged by the photographer with a pair of scissors.

“[He did it] out of anger and frustration, showing that everything in life had been touched by this disaster,” Havinga explains.

Situated in its own nook of the exhibit, Munemasa Takahashi’s “Lost & Found Project” displays family photographs, snapshots of everyday life, salvaged from the wreckage of the disaster. Each one has been washed, digitized, and catalogued, in the hopes of being claimed by survivors. While many have been returned, many others remain a part of the collage, without a rightful owner.

Like the “Lost & Found Project,” much of the tsunami-related work is related to memory, loss, and the importance of place in people’s lives, says Morse, while work created in response to the nuclear disaster draws on a sense of anxiety. For this reason, the works have been divided into two sections within the exhibit.

Photographs related to the nuclear disaster are much more conceptual in nature, as access to the site is limited. Masato Seto, one of the few photographers who have been allowed to visit Fukushima, printed his works in the negative, giving them an X-ray feel. Another photographer, Takashi Homma, collected and documented wild mushrooms in the forests near Fukushima, which had absorbed high levels of radiation. Assembled in Homma’s photographs, the mushrooms also evoke images of the mushroom clouds that rose over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

“This is the only country that has endured two nuclear disasters—major nuclear disasters—that still bought into nuclear energy just the same,” says Havinga. “There’s a lot in this exhibit that’s tied up with Hiroshima, there’s a lot that’s tied up with Japanese national identity.”