Throwback Thursday: When the Senator from Massachusetts Got Caned

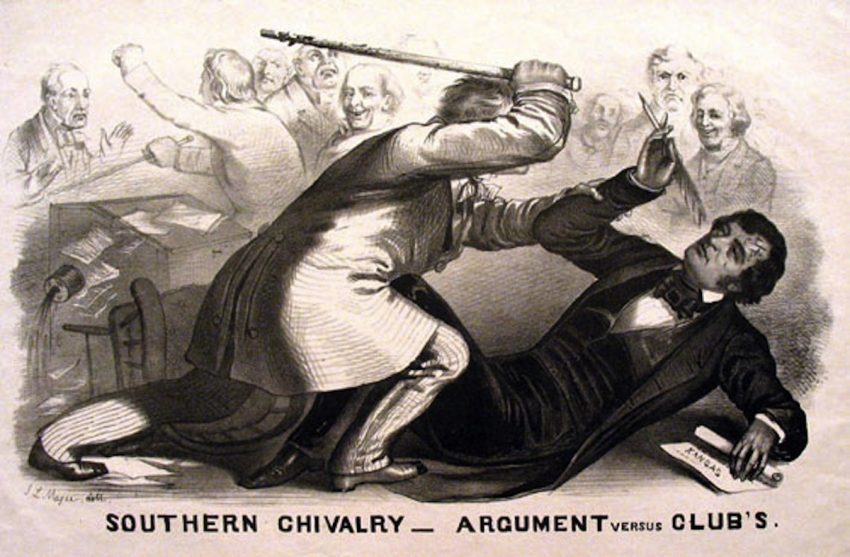

Preston Brooks’ 1856 attack on Charles Sumner via Wikimedia Commons

It’s rare that the floor of the United States Senate ever gets very physically violent. There are never bench-clearing brawls like the recent one in Ukranian Parliament, for instance. But there are occasional exceptions: this week, for instance, marks the anniversary of the most bloody day in Senate history: in 1856, Congressman Preston Brooks viciously beat Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts, leaving him permanently disabled. Then, he got away with it.

The incident came in the run-up to the Civil War, when the nation was intensely divided on the question of slavery. On May 19, 1856, Senator Charles Sumner, outraged at events in Kansas, stood and gave a colorful two-day speech railing against slavery and those who supported it. He included a personal attack on South Carolina’s Senator Andrew Butler, whom he declared “has chosen a mistress. I mean the harlot, slavery.”

Preston Brooks, a South Carolina congressman and distant cousin to Butler, took offense at the attack on his family member, so two days after Sumner’s speech, Brooks walked up to Sumner’s desk on the floor of the U.S. Senate and declared, “You’ve libeled my state and slandered my white-haired old relative, Senator Butler, and I’ve come to punish you for it.” He then raised his cane and proceeded to viciously beat Sumner with it.

If you thought public reaction might have unified against Brooks in the aftermath of the attack, you underestimate the power of politics to make people support vicious assault and battery. The north, of course, was outraged. Sumner never recovered fully from the physical and psychological wounds he endured, and he was unable to resume his place in the Senate for years. Massachusetts continued to elect him, though, leaving his blank seat as a symbol of the South’s sins. The South, meanwhile, actually rallied behind Brooks. He paid a $300 fine, but the House couldn’t put together enough votes to expel him. South Carolina reelected him, and southerners sent him replacements for the cane he had broken over Sumner’s body. The city of Charleston presented him with one that bore the inscription, “Hit him again.” The Civil War was still five years away, but north and south, it seemed, were already terribly divided.