Guess How Many of Marty Walsh’s Campaign Staffers Voted Illegally on His Election Day?

Photo via AP

Unlike 33 states and the District of Columbia, Massachusetts has never allowed what’s called “no-excuse early voting”—the practice of submitting one’s ballot before election day, either in person or by mail. That’s about to change: The Commonwealth will experiment with early voting for the first time in 2016. As it stands now, however, citizens with busy schedules, large families, or multiple jobs have no option other than to find time on election day to get to the polls.

At least, that’s how it works for ordinary people. Many political campaign staffers, on the other hand, play by different rules. Since these staffers are, almost by definition, very, very busy on election day—working tirelessly for their candidates—they often try to use the absentee ballot system to vote days or weeks early, at their convenience.

That’s illegal—it’s voter fraud, technically, and it’s punishable by up to a $10,000 fine and five years in prison. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts allows absentee voting for only three reasons: for voters who will be absent from their city or town on election day; for those who have a physical disability that prevents them from voting at their polling place; and for those who cannot vote at the polls due to religious beliefs.

Voters must swear, with their signature, that one of these three reasons applies in order to receive an absentee ballot.

Nevertheless, Boston-area campaign veterans tell me—on background, to avoid self-incrimination—that absentee voting by staffers is commonplace. More than one admits that they’ve been on campaigns that actively encourage such voting among staff and volunteers. Most claim to be unaware that it’s illegal—which may actually be true, but does not speak well to the care many politicians’ top staffers pay to the legality of their behavior.

Still, until now, I’ve never actually caught a campaign, red-handed, engaged in this particular brand of voter fraud.

With that, we offer congratulations to Marty Walsh’s mayoral campaign of 2013: I found evidence that several Walsh field organizers in that campaign voted illegally by absentee ballot—and all of the offenders went on to work for the city after Walsh took office.

One of these organizers, in fact, is the nephew of the person who was at the time the city’s election commissioner—the same commissioner who sent a stern letter before that election, specifically warning campaigns (including Walsh’s) that such absentee balloting is a crime.

No action was taken against these voting scofflaws, and neither Walsh nor his former campaign manager would talk to me about this.

If you’ve ever been inconvenienced by voting on election day in Boston, you might want to know that the rules don’t seem to apply to the mayor’s own people.

Here’s how it happened.

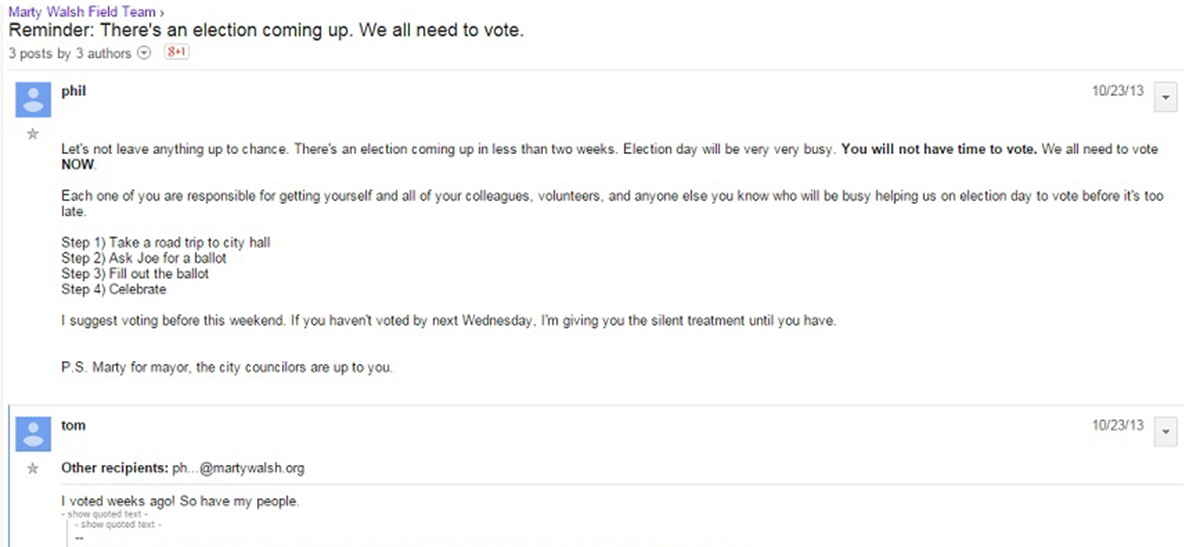

“Election day will be very very busy. You will not have time to vote. We all need to vote NOW.”

So wrote “Phil,” on a message board for Marty Walsh’s field team, on October 23, 2013, 13 days before the final mayoral election of November 5. (The emphasis was in the original email.) I recently stumbled upon this message board, which had been left open to public access—sometime in the past week, after inquiries from Boston magazine, the message board was taken down. Phil is Philip Cohen, who came over from the Felix Arroyo campaign after the September preliminary vote to be Walsh’s deputy field director in the 2013 campaign, and who currently works at the Boston Redevelopment Authority. The post continued:

Each one of you are responsible for getting yourself and all of your colleagues, volunteers, and anyone else you know who will be busy helping us on election day to vote before it’s too late.

Step 1) Take a road trip to city hall

Step 2) Ask Joe for a ballot

Step 3) Fill out the ballot

Step 4) CelebrateI suggest voting before this weekend.

The message board in question was frequently used by top campaign (and later City Hall) staffers Dan Manning and Joe Rull. (To be clear: Rull is not the “Joe” referred to in the above email; that was just the guy who worked the counter at the City Hall elections office.) But if Rull and Manning saw this post, there is no sign that they disapproved: there were no negative comments or warnings posted in response to Cohen’s plea.

“I voted weeks ago! So have my people,” wrote Thomas McKay, the campaign’s field organizer for Charlestown, in response to Cohen’s post. Brendan McSweeney, the field organizer for Hyde Park, also replied on the discussion thread.

Cohen, McKay, and McSweeney all voted by absentee ballot in that November 5 election, according to the Walsh administration’s response to our public-information request. So did two others on the field team who used that message board. One was Rory Cuddyer, the campaign’s field organizer for Roslindale—and, embarrassingly enough, the aforementioned nephew of Boston’s election commissioner at the time. Ditto Yvonne Ortiz, field director for Jamaica Plain. (Matthew Dougherty, who had run the West Roxbury field office during the primary, also voted by absentee ballot, though he says he was no longer actively involved with the campaign: He was in school at Suffolk University full-time during the general election.)

I do not know how many, if any, of “their people”—the much-heralded Walsh armies of get-out-the-vote volunteers—also voted by absentee ballot at their behest.

But it appears that all five Walsh staffers were in Boston throughout election day, and knew that they would be in Boston when they signed their names swearing that they would not be. Their schedules and duties for the day were discussed in other threads on the field team message board. Cohen and Cuddyer even tweeted pictures, or were in pictures sent via social media, showing their whereabouts in the city while the polls were open.

They all still work for the city. McKay is a neighborhood liaison for the Office of Neighborhood Services; Cuddyer is Startup Manager; McSweeney is a project director at the Boston Water and Sewer Commission; and Ortiz works in Walsh’s office.

On October 28, 2013—eight days before the election—Joyce Linehan, then one of Walsh’s top campaign advisors and now his policy director, tweeted that she was “At City Hall, where I just cast my absentee ballot for #bosmayor.” (That tweet has since been deleted.)

I responded on Twitter the next day that she appeared to have confessed to violating the law. A bit of a public discussion ensued.

Linehan claims that she had been expecting to be away on election day because of a family matter unrelated to the campaign. She explained this to me, at the time, via email on the 29th—adding that those plans had coincidentally changed in the 24 hours since she voted, and that she had worked out with the elections department for her to vote on election day after all. She has been unable to provide me with anything or anyone to confirm that explanation.

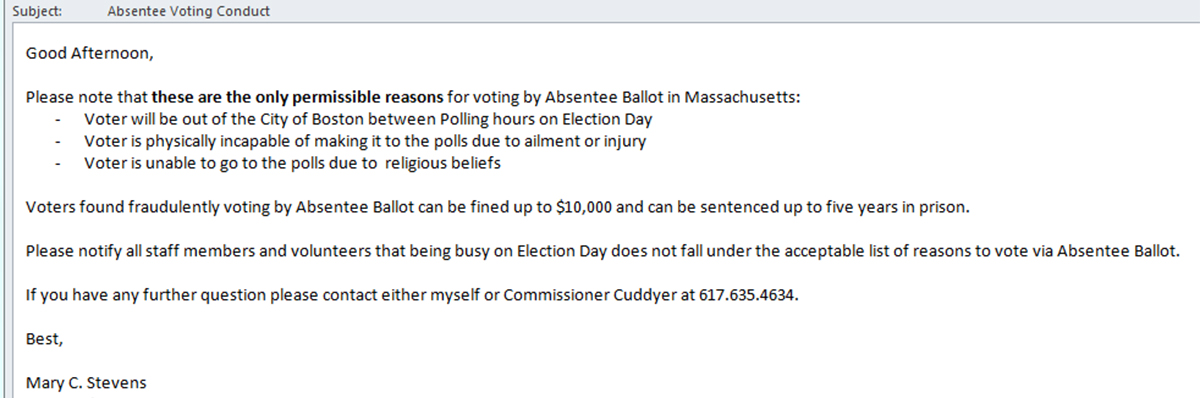

Regardless of whether Linehan’s vote was kosher or not, two days later Boston’s Election Department emailed a stern warning against absentee voting to all the city’s mayoral and city council candidates, including Walsh. I discovered that letter only recently, in the Walsh field team’s message board.

The email, sent on November 1, 2013, emphasized in boldface that the three aforementioned criteria (absent from city, physical disability, religious beliefs) “are the only permissible reasons for voting by Absentee Ballot in Massachusetts.” It went on:

Voters found fraudulently voting by Absentee Ballot can be fined up to $10,000 and can be sentenced up to five years in prison.

Please notify all staff members and volunteers that being busy on Election Day does not fall under the acceptable list of reasons to vote via Absentee Ballot.

By this point, of course, Walsh’s campaign staff had already been urging its people to vote early by absentee ballot.

When the Election Commission email went out to the campaigns, the first name on the blind distribution list (provided to Boston by Walsh’s office at my request) was Walsh campaign manager Megan Costello, currently executive director of Boston’s Women’s Advancement office. The email was also sent to Walsh’s personal email address.

There’s no way to tell for certain whether the Election Commission was responding specifically to Joyce Linehan’s tweet. Geraldine Cuddyer, who was the city’s election commissioner for 10 years before retiring in 2014, says that she did monitor Twitter for voting issues, but does not recall the Linehan incident and does not recall whether there was a specific impetus for the warning letter.

There is reason to think, though, that Walsh’s campaign manager thought that Linehan’s tweet might have prompted the warning letter. In forwarding the Election Commission’s email to campaign staff—and to the field team message board—Megan Costello not only directed everyone to vote in person on election day, she also warned that “EVERYTHING you do on social media over the next 4 days is going to be watched very closely.”

And Costello certainly seemed to take the absentee-voting issue seriously:

…Let me be very clear here:

You need to make a plan for how you’re voting on election day. Working all day is not a valid reason for not getting to the polls….

Please email me back saying you have read and understand this email and with the time you plan on voting…

It’s not clear whether any Walsh staffers who had already voted by absentee ballot undid that deed—as Linehan apparently had done—after Costello’s warning. Records show that Linehan’s vote was recorded in person, not by absentee ballot, although presumably the department did not literally, as she described to me back then, “happily delete[d] and destroy[ed] my ballot.” That would have been flagrantly illegal on their part. But the head of elections for the Secretary of State’s office explains to me that city elections officials can, at the voter’s request and signed certification, hold back the completed absentee ballot to ensure that the in-person vote becomes the first, and only, vote officially counted. Boston’s acting Elections Department director, Sabino Piemonte, provided a statement to me explaining that, when an absentee voter’s “circumstances change… [we] will work with them to rescind their absentee ballot so they can vote in person.” Cuddyer, the commissioner at the time, told me she doesn’t recall ever doing that for anyone, and would not have been inclined to, but allows that it might have happened without her knowing.

It’s hard to know much more, because the Walsh campaign members of the Walsh campaign wouldn’t discuss any of this on the record. But we know this: Despite all of the above, five Walsh staffers still voted via absentee ballot, in what appears to be a clear violation of the law.

Politicians and their campaign teams go to such lengths to understand and adhere to such a myriad of laws governing their behavior, it amazes me that they seem almost universally ignorant of this very straightforward violation.

Cuddyer has long wanted to adopt early voting, but agrees that campaign workers should adhere by the same law that applies to nurses and other hard workers. “My feeling,” she says, “is that it’s incumbent on you to follow the law and impress upon people the need to follow the law. If you want to run the city, you should know the laws that govern it.”

Cuddyer says that she always tried to make sure that campaigns understood and conformed to the law on absentee balloting. She recalls one mayoral election in which a Menino operative called to say that a big group of volunteers were on their way to vote by absentee ballot. “I said, ‘No, they’re not!’”

She says that misuse of absentee balloting by campaigns usually stems from a misunderstanding of the law, particularly by people who previously lived in states with early voting options.

In theory, Cuddyer’s office could have forwarded the names of the Walsh camp’s absentee voters to the District Attorney for investigation and possible prosecution. The stern warning letter notwithstanding, Cuddyer says that such a move would have been extremely unusual; neither she nor the Secretary spokesperson could remember any attempt at prosecuting such a case.

Cuddyer denies that she would have been deterred by the fact that the offending campaign was the incoming boss at City Hall. As to whether she might have backed away because of her nephew’s involvement, Cuddyer seemed genuinely surprised when told that Rory was one of the apparent scofflaws. “I’ll kill that stupid kid,” she muttered on the phone with a chuckle, after several seconds’ silence.