Copper Marvel

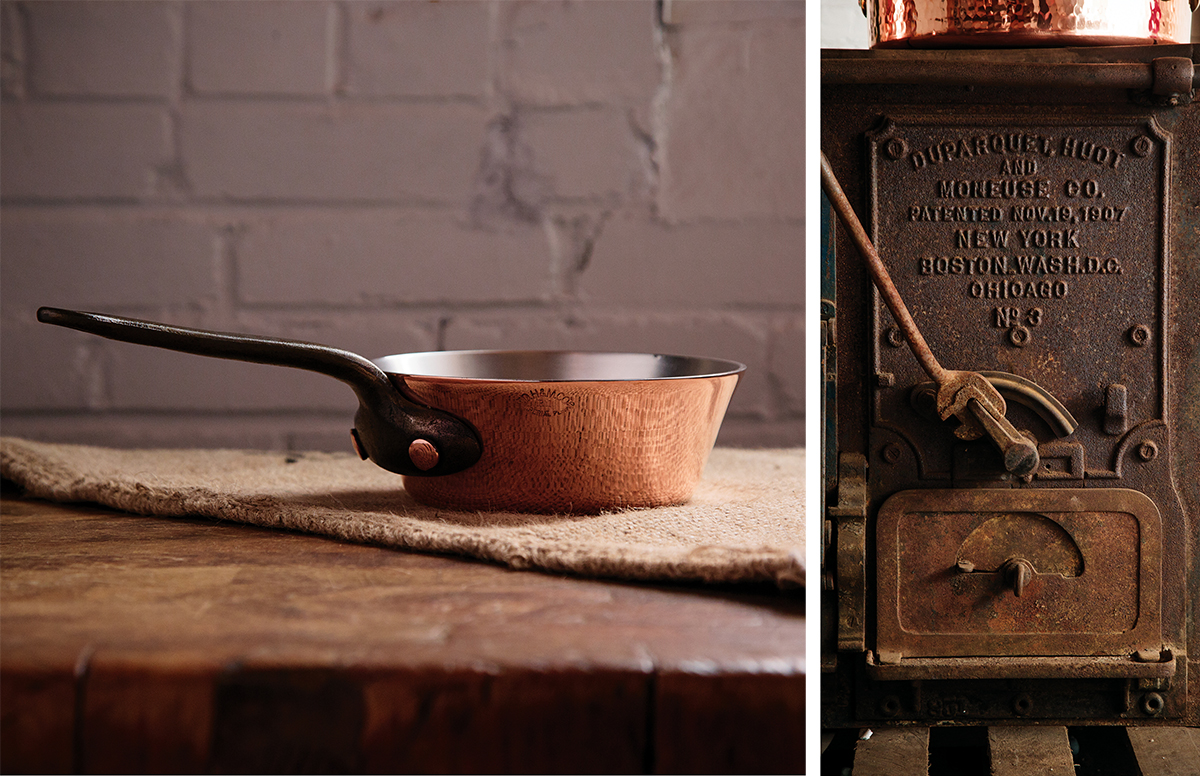

In Hamann’s workshop, refinished copper pots sit atop a cast iron stove from the original Duparquet, Huot & Moneuse, Co. (Photograph by Pat Piasecki)

The art of spinning a sheet of copper into elegant cookware has been somewhat lost on this side of the pond. So much so that when shoppers at the South End kitchen store Farm & Fable pick up a Duparquet, Huot & Moneuse, Co. copper pot, they assume, based on its fine quality and heavy weight, that it was imported from France. “It blows their minds that these pots are made in Rhode Island,” says storeowner Abby Ruettgers.

The craftsman behind these beautiful heirloom pieces is Jim Hamann, a food lover with an engineering background who developed a passion for copper work after purchasing an extra-large (but very dinged-up) stockpot in Burgundy in 2004. When he returned stateside, he committed himself to restoring the pot, researching copperware techniques online and in books. After at least 10 tries, he says, he finally got it right: “I understood what needed to be done technically, but it also had to work and look good.”

Clockwise from top, during refinishing, a pan is stripped to its original copper core; Hamann, outside his Rhode Island workshop; a new pan is drilled for rivets. (Photographs by Pat Piasecki)

On a whim, Hamann set up a website offering copper-cookware restoration and refinishing services out of his East Greenwich workshop. The orders flooded in. He continues to restore pots—stripping them of their aged linings, hammering out dents, and relining and polishing them to their original state. He also sells vintage pieces, using his website as a forum for those looking to buy and trade. But what makes him most notable is that he crafts new pots from scratch, one of the few people in the U.S. to do so using traditional techniques.

Although Hamann and his assistant spin copper in batches, he estimates that it takes a full day to create a piece from start to finish. They begin by cutting circles out of 3-by-8-foot sheets of 1/8-inch-thick copper, which weigh hundreds of pounds. “It’s much thicker than what you’ll find for sale at typical chain cooking stores,” he says. Each copper disk is mounted, one at a time, on a lathe, where it’s spun against a mold, which shapes it into a pot through heat and pressure.

Cookware awaits refinishing (Photograph by Pat Piasecki)

Cast iron is a poor conductor of heat, making it a good material for handles. Hamann orders custom ones from a Rhode Island refinery and secures them with handcrafted rivets—substantially sized and one of Hamann’s favorite features: “The extra-large rivets add character,” he says. Afterward, each pot is carefully lined with tin over high heat and polished to shine.

Finally, Hamann’s new cookware gets stamped with the historical mark of Duparquet, Huot & Moneuse, Co., a defunct New York City kitchenware company that shuttered in 1936, which he has since acquired the rights to. “The brand had such a distinct history, and I wanted to bring it back,” he says.

A collection of cookware showcases the many stages of the retinning process. (Photograph by Pat Piasecki)

Duparquet copper is showcased as servewear for soufflés and savory dishes at the famed Ocean House restaurant, in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, and it’s the go-to sauce pot of Townsman chef Matthew Jennings, who was unable to find a one-quart pot to suit his needs until Hamann worked with him to design and build a custom piece. Jennings feels fortunate to use the “Townsman” pots every day, remarking that they heat evenly and are made with an unparalleled attention to detail.

Hamann has a deep respect for French cookware, and is inspired by Americans’ embrace of farmers markets and farm-to-table cooking. He says that the locavore movement spans generations: “I see people from all age groups who are passionate about food and looking to be proud of what they put on the table.” New England’s rich manufacturing history also inspires him to continue the tradition.

From left: The Fait Tout, or Windsor Pan, is ideal for making sauces; the iron stove in Hamann’s workshop was originally used at a Maine summer camp in the 1930s. (Photographs by Pat Piasecki)

Duparquet’s current line includes three sauté pans, a frying pan, the “Townsman” saucepan, and newer additions, like a butter pan and a small serving bowl. All are hand-tinned and come with a lifetime warranty. Next Hamann will broaden his line to include a French-style pot lid—long-handled and flat for ideal control while cooking.

“I tell people that the cookware is designed to become a new heirloom,” says Ruettgers, of Farm & Fable. “There is no way these pots are leaving your family.”

Hamann lines a copper pot with tin; chunks of tin are melted down to just under 450 degrees Fahrenheit (Photographs by Pat Piasecki)