The History of Boston in Objects

Millions of pages have been written on the history of our city. From Puritans and Revolutionary battles to Whitey Bulger and terrorist attacks, the timeline of Boston is well documented. But city archaeologist Joseph Bagley has a special way of bringing Boston’s evolution to life. In A History of Boston in 50 Artifacts, which comes out in the spring, Bagley delivers a tangible take on our past through a collection of stunning portraits of things that have been unearthed here. Bagley, who is funneling all sales from the book straight back into Boston’s archaeology program, shared some of the standout relics from the archives.

A Fair Trade?

This humble metal weight is most remarkable for its age: Embossed with the royal stamp of Henry VII or Henry VIII, the disk dates back to at least 15th-century England, predating Boston by a century or more, and making it the oldest European object found in Massachusetts. It was discovered on one of the Harbor Islands, and was possibly used as barter between early European explorers and Native Americans.

Native Ingenuity

Buried in clay 40 feet below the Back Bay—from Mass. Ave. all the way to Charles Street—is a sprawling and surprisingly intact Native American fish weir. Built between 3,600 and 5,200 years ago, the fencelike assembly is one of the largest known manmade structures in North America from that era, contemporaneous with the erection of the Egyptian pyramids. Some 65,000 stakes like the one pictured above make up the weir, which Native Americans used to trap fish as the tides went out, providing sustenance for generations.

Unlucky Kitty

In 18th-century Boston, the dark arts occasionally trumped sensible Puritan values, as this unfortunate domestic cat can attest. Its skull was intentionally smashed in, and then its bones were carefully placed in an earthenware bowl and buried under the threshold of the Three Cranes Tavern, a Revolutionary-era watering hole in what is now Charlestown. Chances are this unfortunate feline was a sacrificial offering to fend off evil spirits. As bizarre as it sounds, many a dead cat has been discovered under the thresholds and hearths of homes throughout the U.S. and Europe.

Inky Transcendence

This nib from a quill pen discovered in West Roxbury was likely abandoned by the transcendentalist utopian community that set up shop here in the 1840s. Known as Brook Farm, it attracted the likes of Henry David Thoreau and Nathaniel Hawthorne, who reportedly wrote The Blithedale Romance after spending time at the commune.

Toying Around

The transcendental experiment at Brook Farm quickly failed, and a few decades later, the main farmhouse was converted into an orphanage. This cop-and-robber toy likely belonged to one of the young residents, who appears to have buried it under a bell for safekeeping and then forgotten about it.

The Original iPad

This writing slate was buried in the backyard of the Paul Revere House. Bagley suspects that Irish or Italian immigrants who were living in the North End space in the late 18th century left behind the early educational tool.

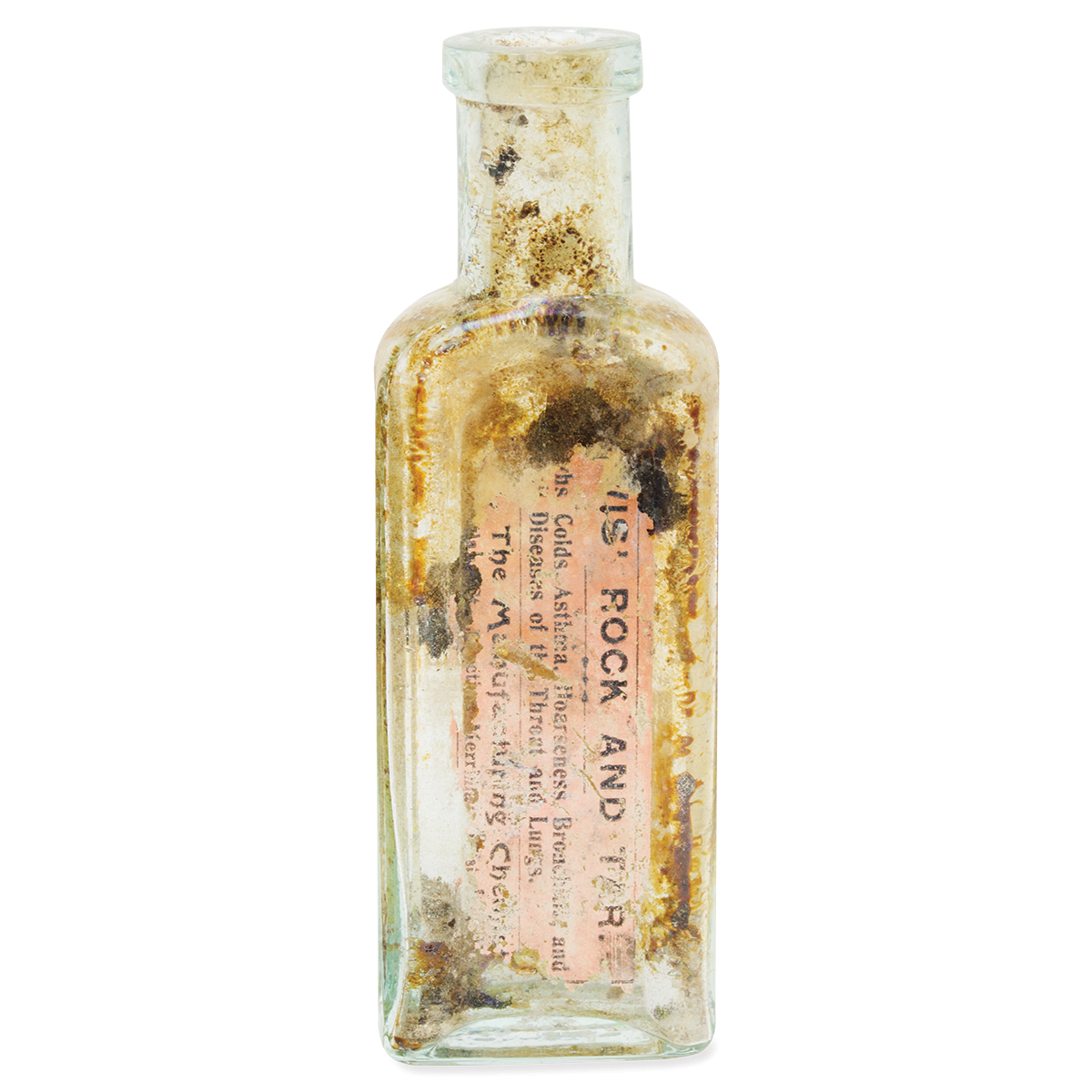

Cure-All

Hundreds of bottles of patent medicines have been discovered all over the city, including this 1895 “Rock and Tar” tincture found in the North End. It was probably sold as a cold remedy; a period photo from the city’s archives reveals a nearby building advertising the product.

Ready, Aim, Fire!

During the Battle of Bunker Hill, on June 17, 1775, this 3-inch-wide, 4-pound cast-iron cannonball screamed out of a British gun and into Charlestown. The assault on the town’s wooden buildings led to an uncontrollable fire, which left behind a hill of rubble—and artifacts that could survive the heat.

Common Cud

Boston Common used to be a whole lot more pastoral—it’s where the Puritans kept their cows starting in the 1600s, a practice that held steady until 1830, when Mayor Harrison Gray Otis banned animals to create the park as we know it. Though the ruminants are gone, their traces remain, including this cowbell unearthed by archaeologists during a survey in 1987.

Before Bobbleheads

This Red Sox “Fan Kid” pin, uncovered in front of the Dillaway-Thomas House, in Roxbury, was given to young fans during either the 1912 or 1914 World Series, both held in the brand-new Fenway Park. Though it measures barely 2 centimeters wide, its detail is impressive—with a baseball face, bats for arms and legs, and a chest-protector torso—all of which would have been brightly painted by hand.

Spiritual Strength

In 1898, as Boston’s black population moved to the South End and Roxbury, the 92-year-old African Meeting House was converted into a synagogue for the city’s burgeoning Jewish population. This page, ripped from a prayer book, was discovered in the walls of the main sanctuary. In 1972, the Museum of African American History acquired the property, now designated a National Historic Landmark.

Spoon-Fed

This ornate silver spoon was designed to commemorate the 1727 coronation of King George II. It was discovered under Faneuil Hall during an excavation in the early 1990s. How it made its way across the pond remains a mystery—Bagley guesses it may have fallen off a ship.

From Puritanism to Porn

From the 1960s through the ’80s, peep shows, prostitutes, and X-rated theaters lined the city’s Combat Zone, along Washington Street between Essex and Kneeland streets, attracting a leering crowd of sailors, students, and businessmen. This token, excavated from the Common in 1987, was good for “one play only” of lascivious entertainment, and is among the youngest items in the city’s archaeology collection.

Long ago, leisure activities were considered criminal, rather than quieting. Case in point: In 1650, Massachusetts Bay Colony legislators were so wary of all “ball sports” that they banned bowling in taverns on the grounds that the game fueled gambling, according to the Massachusetts Historical Commission.

But the discovery of this lawn boule dating back more than 300 years suggests that not everyone played by Puritan rules. Unearthed during an excavation of a privy near the North End, the sporting relic was used in a game akin to bocce.

It’s believed the boule belonged to Katherine Nanny Naylor, a compelling historical figure. Naylor’s father was banished from city limits by religious authorities, and her aunt, Anne Hutchinson, is among history’s most famed heretics. Naylor herself obtained one of the first divorces in the colonies, and her privy was loaded with the telltale signs of a Puritan party animal, including fragments of tobacco pipes and frilly dresses. In other words, Naylor knew how to have a ball.

Adapted from the upcoming book A History of Boston in 50 Artifacts, by city archaeologist Joseph Bagley. / Photographs courtesy of Joseph Bagley