Throwback Thursday: The Disappearance of Dr. George Parkman

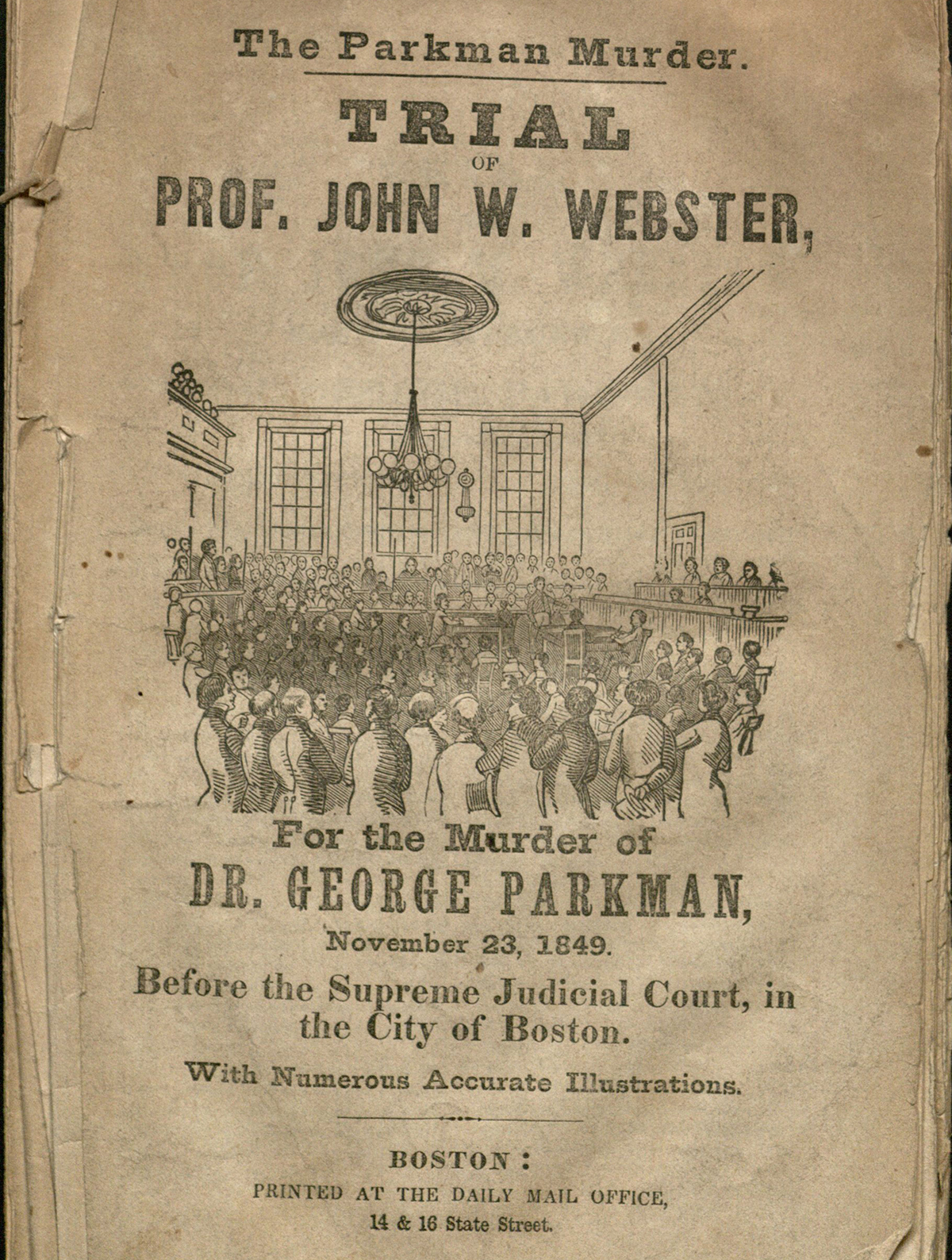

Parkman murder trial record photo via Yale Law Library on Flickr/Creative Commons

Dr. George Parkman’s pointy chin and signature top hat were as recognizable on the streets of Boston as the gas lamps that lit them.

While he came from one of Boston’s richest families, Parkman never purchased a horse. Instead, he walked the city, earning the nickname “the pedestrian.” The Harvard doctor held steadfast to his routine—strolling through Beacon Hill and the West End every day, checking up on his properties and collecting rent payments. So when the 59-year-old didn’t keep his schedule on November 23, 1849, there was cause for concern.

When Parkman didn’t return home, his family plastered thousands of flyers around the city, and the police set out to locate him. They searched his properties and dragged the Charles River in hopes of turning up a body, but found nothing. Some suspected Parkman had fallen into the hands of rowdy Irish immigrants. A $3,000 reward was offered for information about Parkman’s whereabouts.

Parkman was last seen entering Harvard Medical College for an early afternoon visit to Dr. John Webster, a chemistry lecturer who owed Parkman a sum of more than $2,000. Webster had gotten into the habit of racking up debts while living beyond his means. On the same day, the Medical College’s janitor, Ephraim Littlefield, noticed a few peculiar happenings after their meeting. He lived in the basement of the school, next to Webster’s laboratory. While he usually cleaned the labs and maintained fires, Littlefield didn’t tidy Webster’s workspace on November 23. The door to the laboratory was locked that afternoon.

Littlefield later testified that he had seen a flustered Webster carrying a large bundle that day, which Webster claimed was wood for the fire. When police decided to search the Medical School on November 26 and 27, Littlefield thought Webster was trying keep the police away from his privy.

An incredibly suspicious Littlefield made a decision: he would chisel away at the stone wall around Webster’s privy. An excerpt from The Bloody Century by Robert Wilhelm detailed that Webster accessed the privy from the adjacent dissecting room—the room had an opening into the privy where students could dispose of body parts after dissection. Littlefield was sure that Webster killed Parkman, dismembered him, and threw his body parts into the privy. So while his wife acted as a lookout, Littlefield chipped through multiple layers of brick with borrowed tools. He worked all through Thanksgiving Day and the following day—presumably braving the stench—until he could break through the wall. Once he did, he grabbed his lantern and held it to the opening.

His light revealed a glimpse of a human pelvis.

Littlefield immediately reported his findings, and some of the earliest employments of forensic science identified Parkman’s body. The horror turned Boston upside down.

The Boston Brahmins were outraged. What has been called the O.J. Simpson trial of the 19th century commenced, indicting Webster with the murder of Parkman. Newspapers all over the world reported on the case, some sensationally. Since Littlefield collected the $3,000 reward, many Bostonians speculated he framed Webster. Fanny Longfellow, wife of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, wrote,

“Boston is at this moment in sad suspense about the fate of poor Dr. Parkman…You will see by the papers what dark horror overshadows us like an eclipse. Of course we cannot believe Dr. Webster guilty, bad as the evidence looks…Many suspect the janitor, who is known to be a bad man and to have wished for the reward offered for Dr. Parkman’s body.”

In June 1850, Webster confessed to killing Parkman. He claimed he acted in self-defense after Parkman became violent in an argument about Webster’s debts. His confession reads,

“…while he was speaking and gesticulating in the most violent and menacing manner, thrusting the letter and his fist into my face, in my fury I seized whatever thing was handiest, — it was a stick of wood, — and dealt him an instantaneous blow with all the force that passion could give it. I did not know, nor think, nor care where I should hit him, nor how hard, nor to what the effort would be. It was on the side of his head, and there was nothing to break the force of the blow. He fell instantly upon the pavement. There was no second blow. He did not move. I stooped down over him, and he seemed to be lifeless. Blood flowed from his mouth, and I got a sponge and wiped it away. I got some ammonia and applied it to his nose; but without effect. Perhaps I spent ten minutes in attempts to resuscitate him; but I found that he was absolutely dead.”

Webster was publicly hanged that August and is buried in Copp’s Hill Burying Ground.