Massachusetts Media Stands Up for Glenn Beck

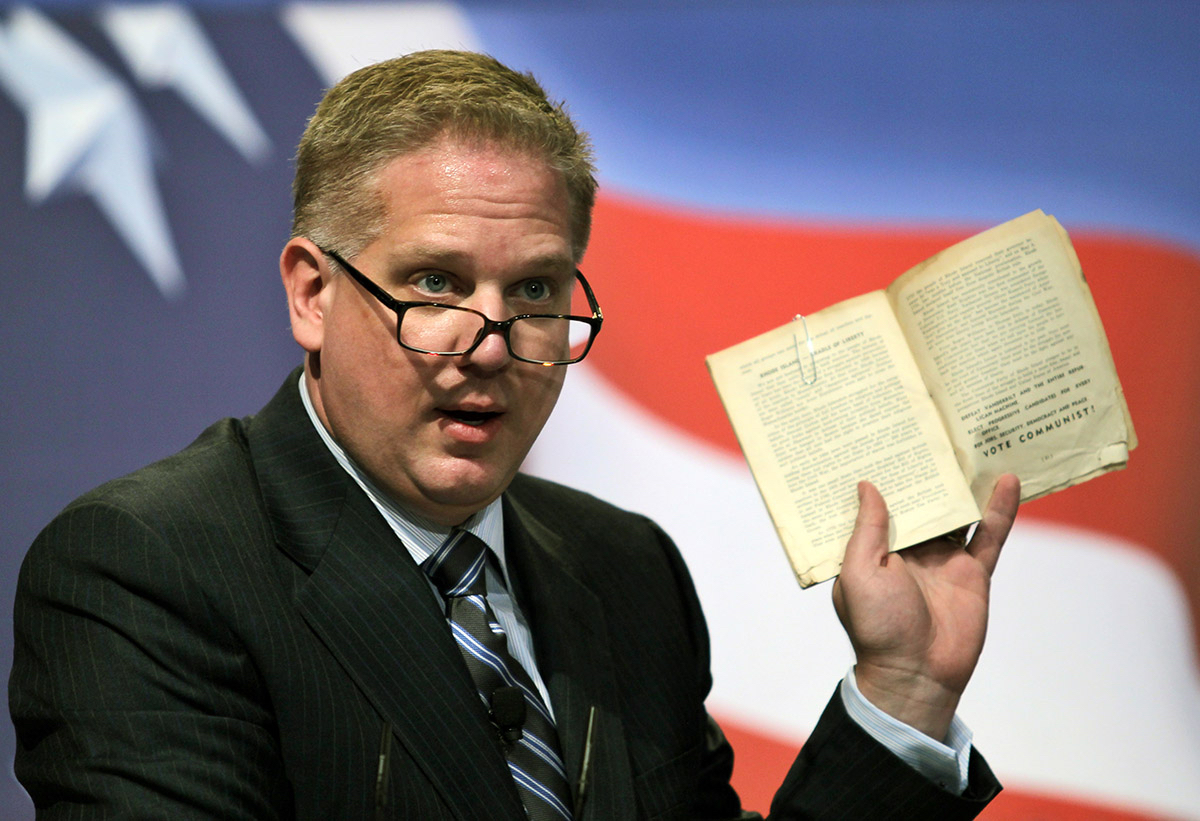

Photo by AP

Glenn Beck is not the easiest guy in the world to defend. But somebody’s got to do it.

And despite the conservative entertainer’s questionable status as a journalist by most traditional definitions, two major local media institutions and a top Boston media lawyer were ready to do just that.

Before U.S District Court Judge Patti Saris ruled this week that Beck must identify the government sources who supposedly fed him information after the Boston Marathon bombings, a team of journalism advocates were ready to swoop in to his defense.

Boston has learned that media lawyer Jonathan Albano (who famously worked with the Boston Globe as its Spotlight team investigated clergy sex abuse in the city and has represented many other outlets) recently penned an amicus, or “friend of the court,” brief arguing for the judge not to make Beck spill the beans on his informants. The Massachusetts Newspaper Publishers Association, the New England Newspaper and Press Association, and the New England First Amendment Coalition also signed off on the brief, which among other things urges the court to consider the implications to a free press.

That’s because, the organizations argue, it’s a big deal when a judge forces a journalist to defy a principle of journalism, even in a case as unsettling this one, and even when that journalist is Glenn Beck.

“In this particular case, it was a little bit more difficult, just because of the highly inflammatory nature of the accusations and issues here,” says Robert Ambrogi, executive director of the MNPA, in an interview. But, he says, “I think the principle that a reporter should be able to report facts based on confidential sources is one that has to be applied across the board, even if you don’t like what the sources are saying or what the reporter is reporting. If you start making judgments like that, you start having standards that amount to censorship.”

Ambrogi says the coalition of media institutions no longer plans to file the brief, as it wouldn’t do any good at this point, but says there have been discussions about playing a more active role in opposing the order if there is an opportunity to do so.

The judge’s order comes as part of a defamation suit filed by Saudi Arabian student and Marathon bombing victim Abdulrahman Alharbi, who police questioned in the hectic aftermath of the attack, then quickly cleared of wrongdoing. Alharbi claims Beck smeared his name by continuing to assert, emphatically and incorrectly, that the 20-year-old was the “money man” for the bombings. Beck also asserted, for good measure, that Alharbi was a “proven terrorist,” and that “we know he is a very bad, bad, bad man.”

Finding out what, exactly, Beck was hearing from his sources—who have been described as top government officials at the Department of Homeland Security—could help the court figure out what justification Beck could have had for dragging Alharbi’s name through the mud, Saris wrote in Tuesday’s 61-page ruling, posted online by Politico. She also found that Alharbi was not a “public figure,” as Beck’s lawyers had argued, which lowers the burden of proof to make a case for defamation.

But Ambrogi says journalists ought to always be able to protect their sources, no matter what they’re accused of doing.

Here’s an excerpt from the motion to introduce the brief:

Massachusetts journalists regularly confront situations in which sources insist on confidentiality in exchange for providing newsworthy information about federal, state and local officials’ performance of their public duties and other matters of legitimate public concern. Judicial determinations of whether a plaintiff has demonstrated a need for the disclosure of confidential news sources and has exhausted alternative sources of the information sought from journalists therefore has a significant impact on the editorial decisions made in newsrooms every day.

Ambrogi says he worries about the chilling effect this, and other cases, could have for others considering sharing information with reporters confidentially. And the underlying issue here, Ambrogi says, is that Massachusetts is among a minority of states without a so-called “shield law,” which would protect reporters in cases like this.

“We, as an organization, have lobbied for the Legislature for quite a number of years to enact a shield law to protect reporters’ sources,” he says. “They have chosen not to do that.”

Beck has weighed in on all of this, but has a slightly different take.

He argued on his radio show (and in this video clip) that if he identifies his sources, it could lead to them being assassinated—appearing, as Politico reports, to cite a theory that a recently deceased Democratic National Convention staffer was murdered for politically-motivated reasons.

“I will tell you this,” Beck says, removing his glasses. “Read the papers. Read the Internet. Sources are under attack. Confidential sources are under attack and you cannot reveal confidential sources because there are sources that are concerned about this very kind of thing. … Have we crossed the line to where our government or our politicians or political institutions now feel comfortable enough to where they will kill you? Now that sounds crazy, but are we not moving towards Russia?”

Or, you know, because of the First Amendment.

Here’s a copy of both the amicus brief obtained by Boston, as well as the motion to introduce it, neither of which made it to court:

(201044418)_(1)_v. 2 Beck amicus motion by spencer buell on Scribd

(201019900)_(2)_v. 2 Beck amicus brief by spencer buell on Scribd