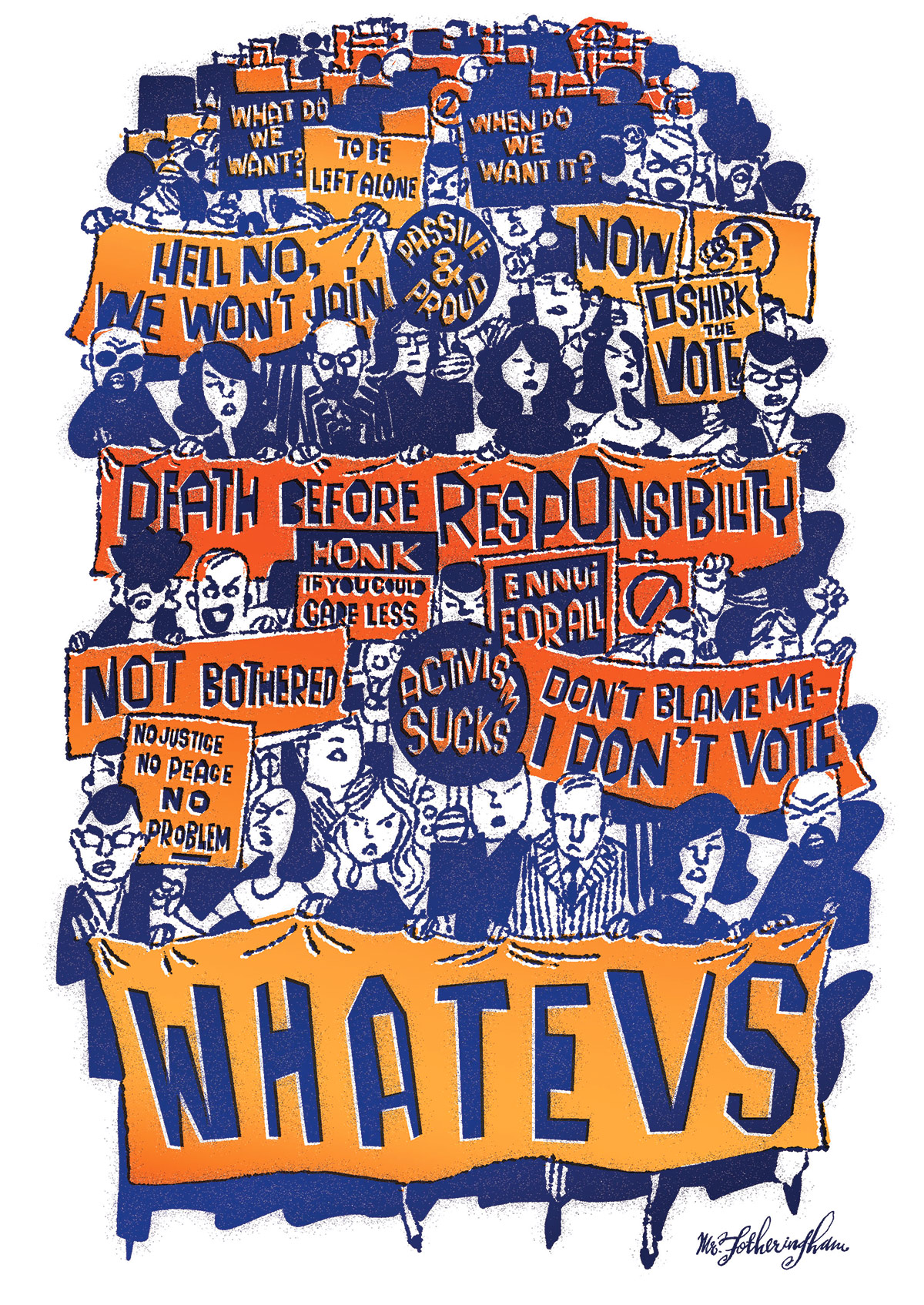

The Cradle of Apathy

Illustration by Edwin Fotheringham

Do you care only about yourself? Do you feel bad about it? If not, you may continue with the grasping, solipsistic travesty you tell yourself is a life. Best of luck. If you do feel bad, however, help would seem to be on the way, to judge from this month’s first-ever Boston Civic Summit. City council president Maureen Feeney conceived the event following the embarrassing 13 percent voter turnout in last November’s municipal elections, then signed up a board full of A-list backers, including Jarrett Barrios from Blue Cross Blue Shield and superlawyer Cheryl Cronin. Invite Bostonians to air their concerns about the state of the city, the thinking goes, and you might figure out why so many have become disengaged.

For the most part, the media (okay, chiefly me, writing on this magazine’s blog) have so far monomaniacally focused on the political implications of the event—specifically how, when the reenergized council president first went to the press with her idea in January, Hizzoner nearly burst into flames. (Councilors holding summits to diagnose citywide problems is a big no-no in Tom Menino’s Boston.) But here I want to focus more on whether things have, in fact, gotten bad enough to necessitate a whole summit on apathy in the first place, and if so, whether the voters’ apathy is actually justified. Feeney has spoken of how “that great ‘torch’ of civic leadership that was passed to my generation is being kept aglow by hands that are too few and too tired,” implying that the youth (what with their iPods and so forth) are at fault for this supposed mass disengagement. But the reality is, the low voter turnout and the disengagement it implies is less an indictment of Boston’s young people than it is one of a city government that’s failed time and time again to prove its relevancy to young people. By many indications, they already do care about the city—just not the ghastly parcel City Hall is sitting on. And it’s hard to blame them.

When social scientists talk about civic engagement, it can mean a number of things—from voting to volunteering, to protesting, to inviting neighbors over for a cookout, to reading the paper—all of which reinforce one another. Say you move into a house on a block where people make an effort to know their neighbors. You get over your natural Bostonian distrust of strangers and get to know the person next door, who happens to volunteer with, say, Boston Cares.

You’ve always felt vaguely guilty about never volunteering (you are, after all, an overeducated white liberal with spare time), but like most people you’re inclined to wait until you’ve been asked. So you and your neighbor start volunteering at a local afterschool program, teaching poor kids to read. After a few weeks of that, a bell goes off in your head. You think, “Wow, this town is a disaster. I’d better go vote someone out of office!”

Now, here’s what’s so interesting about Boston’s present predicament. You would expect, judging by the pitiful voter turnout, that residents as a whole have sunk into the rank well of self-involvement that the social-isolationist boomers disappeared into years ago. Not necessarily. Enrollment in Boston Cares, which works with more than 165 schools and nonprofits, jumped 30 percent last year, just as it did the year before, and is on pace to do so again this year. City Year Boston’s Young Heroes and City Heroes programs, which enlist middle and high schoolers to help out in their communities, have seen enrollment climb 25 percent and nearly 50 percent, respectively. The Greater Boston Food Bank has gone from 11,000 volunteer visits to 16,500 in the span of two years. Donations to the Boston Foundation, which distributed $92 million to area nonprofits last year, doubled between 2006 and 2007.

The local volunteerism boomlet is part of a national pattern, says Tom Sander, who studies civic engagement at Harvard. After decades of steep decline, culminating in that orgy of consumerism and self-worship now popularly known as “the ’80s,” young people started volunteering at an accelerated rate in the early 1990s. At the same time, they remained uninterested in politics, in part because they didn’t view government as capable of dealing with any of the issues they cared about. But after September 11, they began to pair their increased volunteerism with political activism, having seen how interrelated society’s problems actually are. Today that combination, notes Sander, is “evidence of what we’re calling a ‘9/11 Generation,’ or what some people are calling a ‘New Greatest Generation.'”

In Boston, however, we have the jump in volunteerism without the renewed interest in politics. This isn’t to suggest we’re politics-averse—just local politics–averse. Some 36,000 more Bostonians voted in this year’s presidential primaries than in the 2005 mayoral election—which, at 97,160 ballots cast, was considered to have had pretty solid turnout (more than double that of the council elections two years later). During the 2006 gubernatorial race, the turnout in Boston was so strong that many precincts ran out of ballots; in the end, more than 157,000 people voted. It all points to a glaring disconnect: The same people who have Barack Obama posters on their walls and spent weekends campaigning for Deval wouldn’t know Steve Murphy if he fell on their head.

Steve Murphy is an at-large city councilor.

As the past few state and national elections have proven, although people have lost that old sense of obligation to vote, they will go to the polls if they feel something is at stake. But that’s the trouble with city elections: Nothing’s ever really at stake. The council has little power, and ultimately can’t get anything done without the consent of an omnipotent mayor who cannot, it seems, ever be ousted, and who many younger residents (unfairly) think is a moron not worth a vote for or against.

If city politicians are serious about getting out the vote, then, it puts them in the unenviable position of first admitting that Boston’s reputation for being a hard-core political town has officially become bogus, and subsequently swallowing their pride and going out and justifying their very livelihood to Bostonians who don’t see the point in hauling themselves out on Election Day. Unfortunately, the best way to engage those voters isn’t by stressing the bread-and-butter constituent services that are a councilor’s bailiwick. It’s by articulating a compelling vision for the city that people will want to sign on to—which for a councilor will also likely result in the Menino machine’s catapulting him or her out of City Hall and back into powerless obscurity.

But that’s not to say it can’t happen. Interestingly, for all the beatings Deval Patrick has taken lately, he did follow through on his campaign calls for more public service by launching the Commonwealth Corps—an initiative that aims to create an initial force of 250 volunteers pledging yearlong commitments to various causes—as well as broadening the SERV program, which offers incentives for state employees to pitch in. With her summit, Feeney could develop the same sort of cachet, and form the kind of profile that increasingly appeals to the younger voters she’s hoping to bring back into the fold. Frankly, though, too much of this stuff and she may need a volunteer corps of her own to fend off a certain rampaging mayor. Any takers?