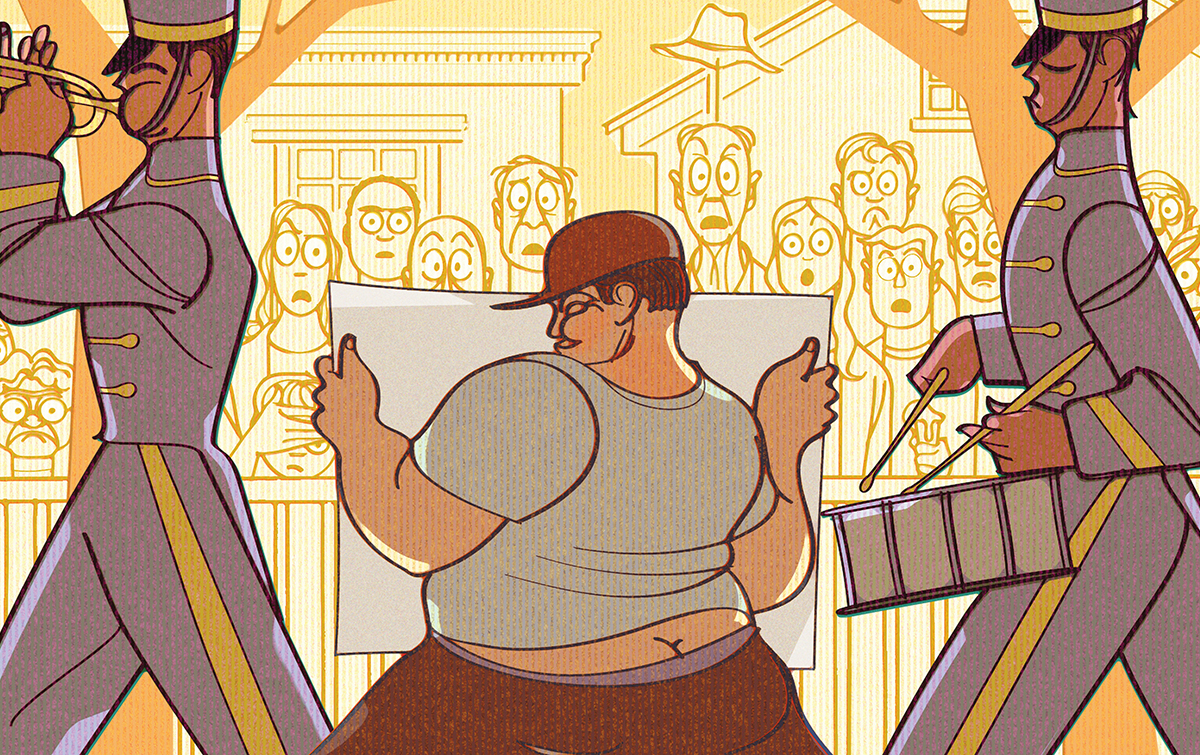

Beverly Farms’ Parade of Horribles

Illustration by Eric Palma

In June 2008, international scandal rocked Gloucester when Time magazine reported that 17 girls at the local high school had all become pregnant as part of a bizarre teenage pact. Major media outlets from New York to Tokyo trained their attention on the small fishing town with breathless curiosity and considerable handwringing. But to a few folks in Beverly Farms, a mere 10 miles away, it was comedy gold.

“The Farms,” as residents call the neighborhood, is the wealthier, oceanfront side of the tracks in the city of Beverly, known for titans of industry whose mansions overlook Great Misery Island in Salem Sound. For generations, the community’s Fourth of July festivities have included fireworks, scavenger hunts, and cookouts. But perhaps the most notable attraction is the annual Horribles Parade down its quaint main street, in which participants ridicule public officials, celebrities, and even neighbors in the most outlandish (and politically incorrect) ways. Over the years, this has included everything from a Jeffrey Dahmer–spoofing float draped in butcher bones and meat to floats humiliating townspeople with known opioid problems.

The neighborhood had been reveling in this gleefully gruesome pageant of one-upmanship for decades—but in 2008, inspired by the Gloucester media frenzy, the Horribles outdid themselves with a procession of pregnancy-pact-themed floats. Spectators, old and young alike, watched in awe as a giant water-spraying phallus cruised by, flanked by a woman in stirrups simulating the birth of a grown man dressed in diapers. Other marchers sported fake baby bumps, brandished signs declaring the Gloucester teens “pregnant tramps,” and pelted bystanders with candy and condoms. The float was a hit with the parade committee, which awarded one of the teams second place in the annual competition for best float. Gloucester, meanwhile, was understandably less thrilled, its mayor reportedly “deeply offended.”

Stirring up trouble was nothing new for the Horribles Parade, but in the past, controversies had stayed local and usually blew over quickly. This time, however, footage made its way onto YouTube. The video went viral and network television trucks once again descended upon the North Shore. Thrust into the national spotlight in a new age of political correctness—a time when universities ban controversial speakers and National Lampoon–style hijinks draw national outrage—Beverly Farms’ centuries-old tradition made headlines in news outlets from CNN and USA Today to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Much of the coverage focused on the cringe-inducing spectacle of a well-to-do enclave picking on teenagers from a more working-class hamlet. “Was it a ‘class war’ or just classless?” ABC News wondered. It didn’t take YouTube long to deem the parade footage sufficiently “inappropriate” to remove it, relegating it to the likes of LiveLeak, an anything-goes website best known for hosting clips of terrorist beheadings and car wrecks.

In response, the mayors of Beverly and Salem—another town that had mocked the Gloucester girls in its own parade—issued a joint statement criticizing the “unauthorized activities of a few very misguided persons.” Brett Schetzsle, then a member of the Beverly Farms parade organizing committee, told the press, “The parade has been going on for 130 years, and at some point nobody thought to adjust to the fact that we live in a YouTube world now.” The members of the nonprofit committee responsible for vetting Beverly Farms’ floats were largely unapologetic.

By now, though, battle lines were clearly drawn. In one camp were those who viewed the parade as a bastion of privileged frat-boy humor, too crass and hateful for a family-friendly Fourth of July celebration. In the other: the pro-Horribles, fighting not just for their annual right to drunkenly craft floats bearing signs with lewd rhymes, but also to keep the nanny-staters from censoring a tradition dating back generations—one that has always celebrated satire and freedom of expression, no matter how crude, over delicate sensibilities and hurt feelings. Ever the diplomat, then-Beverly Mayor Bill Scanlon wanted to believe that the Horribles Parade would clean up its act, speculating publicly “it will probably take care of itself.”

And for a few years, it did. The world largely forgot about the controversy, and the Horribles returned each July—although it hadn’t exactly cleaned up its act. One year, for instance, a float mocked Tiger Woods’s infidelity scandal with a sign calling him “Vanilla Gorilla the Vagina Killa.” But the parade was simply escaping notice the same way it had before. Then last year, amid the divisive election season, controversy erupted once again. This time, critics singled out several floats, including one of Donald Trump—and his great big wall—as well as those poking fun at Hillary Clinton, transgender bathroom laws, and Black Lives Matter.

Now, a month before this year’s parade, the Horribles wars in Beverly Farms have reached a fever pitch, fueling animosity as well as speculation throughout the community that—in the wake of Trump’s election—the event will be at its most offensive. Opponents battling to shut down the parade for good are lobbying sponsors to pull out. Meanwhile, the float-making faithful are sticking to their guns, prepared to march no matter what. Unanswered, though, is the central question that will likely determine the parade’s fate: In an era that somehow includes both the rise of PC culture and a president who brags about groping women, should we impugn this gaggle of equal-opportunity offenders stomping down the street as nothing more than a parade of trolls? Or should we defend this tradition that encourages us to laugh at ourselves at a time when we need it most?

While it’s become a signature event for Beverly, the Horribles Parade didn’t start there—nor is it the only one in Massachusetts. The concept was born from centuries-old New England celebrations soaked in resistance, satire, and booze. Richard Trask, the town archivist for Danvers, which has long held its own Horribles Parade, believes that the tradition is a melding of a few separate holidays, including: Guy Fawkes Day, an annual celebration in England of the man who tried to blow up Parliament in 1605; Pope’s Day, a 1700s anti-Catholic tradition in which townspeople decked out homemade coaches and hung effigies of His Holiness; and a summer celebration during which freed and enslaved African-Americans were given a single day to dance and otherwise engage in “venting,” as Trask puts it.

For more than a century, Horribles Parades have been taking place in a cluster of North Shore towns, including Winthrop, Salem, Manchester-by-the-Sea, and Marblehead. The definition of “horrible” varies wildly. In Danvers, for instance, the parade is a lighthearted children’s event in which marchers dress up as, say, Finding Dory characters; in Salem, meanwhile, a recent float skewered Penn State over its pedophilia scandal.

The Beverly Farms version is said to be more than a hundred years old, though its exact history is hard to pin down. What’s clear is that this particular parade has been tweaking nerves since at least the 1970s. During that decade, Beverly Farms native David Hackett, then a child, recalls protesters tailing a float that was making fun of welfare recipients. Back then, the event was a bigger part of the town’s Fourth of July festivities, he says. Now he claims it’s down to roughly half a dozen groups doing their best to keep the tradition alive—something he strongly believes in. “It’s political satire,” says Hackett, a mailman with a deep Boston brogue. “I call it lampooning. It’s just something you’re born into here.”

Jimmy Dunn, a Beverly-bred standup comedian, acknowledges that “malice” is a key ingredient in many of the floats, but says it’s a misconception that they’re the work of rich residents mocking the less fortunate. “The people who make these floats,” says Dunn, himself the son of a house painter, “are blue-collar, and the targets are usually the rich guy.” No target ever appears to be off-limits.

Yet, there does seem to be such a thing as going too far—something that Hackett discovered firsthand. Several years ago, inspired by an incident in which a wealthy Beverly broker was placed under investigation for stock manipulation, Hackett built a float that looked like a prison cell, dressed up in a suit and tie, and blasted “If I Were a Rich Man,” from Fiddler on the Roof, all along the parade route. That apparently didn’t sit well with many in Beverly: The stockbroker was a popular figure, Hackett says, and the backlash over the float divided the town, subjecting Hackett to an extended silent treatment. “I went a year,” he says, “without talking to people.”

As any standup comic can tell you, though, ridicule also has the power to bring catharsis. Not long after Dunn was let go from a sitcom on national TV, the comedian remembers with a chuckle, his cousins built a float bearing a picture of his face with the word “CANCELLED” written all over it—providing him with a much-needed emotional release. Dunn doesn’t think he’s the only one who could benefit from the ribbing: After the tumultuous 2016 election, he says, it seems we all could use a laugh.

Still, that’s not good enough reason to justify the parade’s existence, at least not to Beverly resident Norrie Gall, the town’s most vocal Horribles opponent. Gall—whose day job involves fundraising for a liberal religious movement where even atheists are welcome—refers to herself, somewhat self-effacingly, as a “social justice warrior.” She also freely admits she never actually spends Fourth of July in Beverly Farms, dismissing the tonier neighborhood as Animal House in boat shoes compared with the rest of Beverly. And yet this soft-spoken single mom has become the face of the movement to drive a spike into the heart of the Horribles Parade.

The crusade began last July, when Gall came across a collection of parade photos online and was appalled by floats she regarded as homophobic, cruel, and racially insensitive. Float-makers mocked the issue of transgender bathrooms (“Will he take a piss or spy on your miss,” read one sign), ridiculed children suffering from the Zika virus (“Having a tiny head kind of blows, the only job I’ll ever get is working at Lowe’s”), and co-opted a hashtag from civil rights activists to satirize the shooting death of the Cincinnati gorilla Harambe (#GorillaLivesMatter”). She calls the parade’s worst content “hate speech.”

Unlike past critics, Gall didn’t bother complaining to parade organizers. Instead, she took to Facebook to directly pressure sponsors, including Salem Five Bank, to withdraw their financial support for the 2017 parade. Though she agrees that Horribles participants should be allowed to espouse their views, Gall maintains that she’s just exercising her own right to free speech. “I don’t want a Klan parade down the street near my house, but that’s legal,” she says. “And if a bank is sponsoring it, I’m going to raise hell with the bank.”

Gall’s rabble-rousing reignited the controversy. Salem Five responded online that the event was “over-the-top tasteless…and certainly not fit for children,” vowing to pull its sponsorship of the entire Fourth of July festivities if Beverly Farms didn’t end its Horribles Parade. (A Salem Five rep has confirmed that the bank is not a sponsor this year.) City Councilor Estelle Rand publicly denounced the event; Beverly Mayor Michael Cahill agreed some of the floats were in poor taste but cautioned, “There are free-speech rights involved here.” Meanwhile, the issue became a powder keg on Facebook. Residents complained of being subjected to homophobic or racist floats disguised as humor, while other commenters decried the “politically correct gang” attempting to derail a local tradition. As a result, this year’s parade is shaping up to be the most explosive yet.

With July fast approaching, the question on many minds is what the float-builders will come up with this year. Between Trump, Russian hackers, and the national slugfest over sanctuary cities, the year’s headlines have provided plenty of grist for satire, tone-deaf or otherwise. Despite the outrage, parade veterans seem to think the event can unite us in these troubled political times. After all, they reason, what liberal wouldn’t enjoy the opportunity to blow off steam by lobbing a good barb at the very president they loathe?

Still, many—including Hackett, who’s certainly experienced his share of post-parade fallout—fear that today’s protest culture will derail the time-honored event. “A day of fun offends people,” he says, before admitting that many of the floats are, in fact, objectionable. “They’re intended to be offensive, but it’s supposed to be one day and you go on with your life.” But times have changed: “The whole world has gotten softer,” Dunn laments.

As it stands, despite Gall’s efforts and the fact that the bank has indeed pulled its sponsorship, official reaction to the parade has been muted. The parade committee states in all caps on its entry forms that floats displaying “racial, religious, sexual orientation or ethnic slurs [or] explicit sexual content of any kind” will not be tolerated. Although, as Rand points out with a laugh, the rules “also say there are no alcoholic beverages consumed.” For participants, getting floats past the vetting process has long been part of the fun.

Rand, though, hopes to tone things down this year: Citing a raft of complaints she’s received about the parade since her election in 2013, she’s suggested putting a member of the town’s Human Rights Committee on the vetting panel, but she hasn’t heard back from the parade coordinators. (No member of the committee, including its longtime parade organizer, Don MacQuarrie, replied to messages requesting comment for this story.) For now, her idea seems unlikely.

What is likely, though, is that Gall has become yet another figure for the Horribles to skewer—perhaps even earning her own float. Hackett, who has no plans to take part in this year’s festivities, believes there will surely be signs targeting her. “If you attack ours,” he explains, “we’re going to come back at you.” For her part, Gall isn’t happy with how parade plans are progressing so far, but she’s still hoping that class will defeat crass this time around. If the parade goes off as usual, though, she’s confident in her backup plan: “I’m going camping that week.”