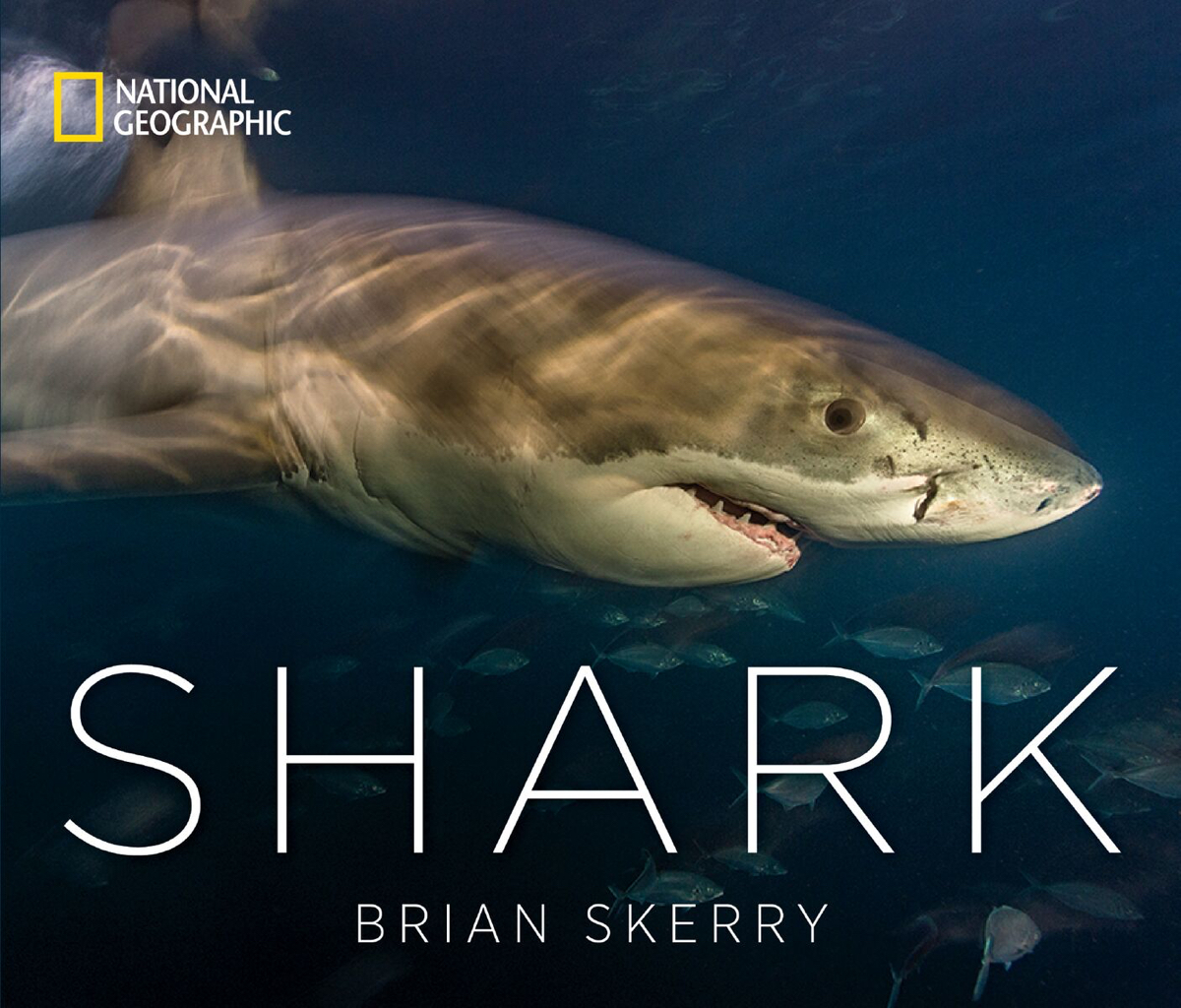

Brian Skerry, Shark Photographer, Wants Us to Stop Ruining the Ocean

Photo by Brian Skerry

Flip through Milford native Brian Skerry’s upcoming book of shark pictures, Shark, and you’ll see dozens of breathtaking images: an Australian Great White smashing its huge body through the ocean’s surface with its jaws agape; a whale shark wrapped in a cyclone of smaller scad fish in the Gulf of Mexico; and a sand tiger shark baring its dozens of teeth off the Japanese coast. Skerry gets his camera mere inches away from his subjects to produce some of the most intimate portraits of the fearsome and fascinating creatures you’ll ever see.

But read Shark to the end, and it’s the last few pictures that will stick in your mind. In one taken in Montauk, young sport fishermen grin next to a juvenile shark caught and killed at a competition. In another, a shark dangles underwater trapped in a commercial fishing net. Then there’s the image of a dozen or so blood-soaked mako sharks flopped on a beach, their dorsal fins lopped off for soup. Those shots tell the horrific story of what’s happening to sharks every day, and it’s a story that has haunted Skerry for much of his career.

It’s an animal that has been sculpted by nature to be absolutely exquisite. It’s a perfect blend of grace and power.

After decades of documenting sharks and their fragile environment, Skerry can’t help but dwell on the many ways in which mankind has trashed the oceans and imperiled sea life. This is something he worries about day in and day out, and he thinks the rest of us are not nearly worried enough. “If all we ever see are the sort of pictures that tell us everything is OK,” he tells me, “then we’ll think everything is OK.”

But as Skerry knows all too well, everything is not OK. Each year, an estimated 100 million sharks are fished and killed, in some cases nearly to extinction, often just to harvest their fins for tasteless yet coveted shark fin soup. Meanwhile, ocean acidification, which occurs when the ocean’s chemical makeup changes along with greater levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, is bleaching coral reefs and disrupting shark behavior around the world. And Skerry, who has spent more than 10,000 hours underwater over 40 years, has watched and recorded this slow decline, month after month, year after year.

“I started diving in the 1970s, and I used to walk off the beaches in Gloucester or Cape Cod or wherever, and I used to see codfish, and pollack—schools of baby pollack—and flounder, and all kinds of things. When I go diving today in New England, I don’t see those things. They’re gone,” he says. “Unless you do what I do, unless you poke your head under the water on a regular basis, you wouldn’t know that.”

Photo by Spencer Buell

I first get to see Skerry in his role as ocean evangelist on a drizzly Thursday morning in May at the New England Aquarium, where he is the “explorer in residence,” and an exhibit called “Science of Sharks” is now on view. Seated on stools, he and marine biologist Greg Skomal pose for pictures and field questions from a handful of reporters. The room is teeming with shark stuff—there’s a tank full of tiny shark species; a handful of incubating epaulette shark eggs; digital displays with information about what makes the animals tick; and a trio of screens on which a highlight reel of Skerry’s work plays on a loop. Skerry looks at home and is gushing about sharks.

“It’s an animal that has been sculpted by nature to be absolutely exquisite,” he says. “It’s a perfect blend of grace and power. They move elegantly through the water, and yet they exude this tremendous confidence.” The time has come, he says, to “bring them out of the shadows.”

Not too long ago, the word “shark” conjured images of the monstrous fictional creature from Jaws. But that’s changing. There is greater awareness of conservation issues now, Skerry says, and people have come to respect the animal rather than fear it. Sharks have also gotten some good PR as of late. Recently, after long-term preservation efforts like banning seal-hunting have caused shark numbers to rebound off the coast, “everything exploded in terms of media and attention,” says Skomal, the state’s top expert on sharks and one of Skerry’s longtime scientific collaborators. Media-savvy advocacy groups like Cape Cod’s Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, national TV programming like the Discovery Channel’s Shark Week, and the ascendance of social media icons like Mary Lee have helped make shark conservation part of pop culture.

There is a fine line, though, between being an enthusiastic ambassador for sharks and an environmental scold, and Skerry is conscious of the divide every time he gives a lecture, appears on TV, or hosts a press event. “Being adversarial is never productive,” he says. “I just want to share what I believe to be true. Human beings are visual creatures, we respond emotionally to photographs, and we can change behaviors because of that.”

But what about the competitive shark fishermen featured in his book, the ones using expensive deep-sea fishing equipment to kill young sharks? Can photography help change their ways? Skerry insists that it can. “If you see beautiful pictures of mako sharks underwater and they look ferocious and beautiful, and you understand their amazing biology and all that stuff—and then you see a baby one being held up on a dock, you could maybe say, ‘Maybe we don’t have to do that.’”

Photos from “Shark”

It’s not only families at the aquarium and extreme fishing hobbyists that Skerry needs to convince to take the ocean seriously. He has a set of policy prescriptions to help preserve marine life that he’d like to see enacted. He believes we need a massive expansion of marine protected areas—we should be protecting 30 percent of the ocean, he says, but we’ve only protected about 3 percent worldwide. We also need tougher restrictions on the global commercial fishing industry, he says, and we need to rein in the damaging effects of pollution and climate change. But with the current occupants of the White House, it’s an uphill battle.

Consider that over the past six months President Trump has proposed deep cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency, appointed a climate change skeptic to helm it, and pushed for rolling back regulations and re-negotiating water cleanup efforts. He also pulled the U.S. out of the Paris climate accord, and moved to green-light oil exploration in the Atlantic Ocean—including plans to OK a new method called seismic testing, which emits a deafening sound at the ocean’s floor that disrupts marine life for thousands of miles.

If that wasn’t bad enough, there’s the fact that Trump harbors an inexplicable disdain for sharks. After facing criticism in 2013 for serving shark fin soup at his now-closed Trump Taj Mahal casino, Trump tweeted that he’s “just not a fan of sharks” and that they are “last on my list,” adding, “don’t worry, they will be around long after we are gone.”

Trump’s approach to conservation is a sharp deviation from President Obama’s. Even if conservationists couldn’t get their all of their goals achieved under the former president, he protected more of the ocean than any president before him and established the first-ever marine national park in the Atlantic Ocean, an area the size of Connecticut off the Cape Cod coast. Obama has said he’s a fan of Skerry’s work, and during the then-president’s trip last summer to his home state of Hawaii, he invited Skerry to join him for a dive. That’s where Skerry famously shot the only underwater photo of a sitting American president.

Still, Skerry isn’t giving up on Trump. He sincerely believes that with enough time, he can get through to the new president. When we spoke on the phone, he’d recently given a lecture to what he described as a bipartisan crowd at NatGeo headquarters in Washington, DC, which included a slideshow of American presidents—Nixon, Reagan, Bush, Kennedy—extolling the virtues of preservation. “Protecting the environment should not be, and historically in this country has not been, a partisan issue,” he says. “I think if I put a group of reasonable people in a room anywhere in the world and show them what I’ve learned, I think the vast majority of them will walk away and say, ‘That makes sense.’”

He hasn’t spoken to Trump, or communicated with any other higher-ups in the White House, but he’s got some ideas, and is “looking at some long-term goals.” Will he ever photograph Trump among the natural wonders of the ocean, like he did with Obama? “I hope so,” he says. “If I could get our new president to see these things and care about them and realize how important they are for business and industry and commerce and weather and everything else that matters, then, boy, wouldn’t that be great?”

Brian Skerry’s new book, Shark, comes out June 13.