Chasing the Midnight Ghost

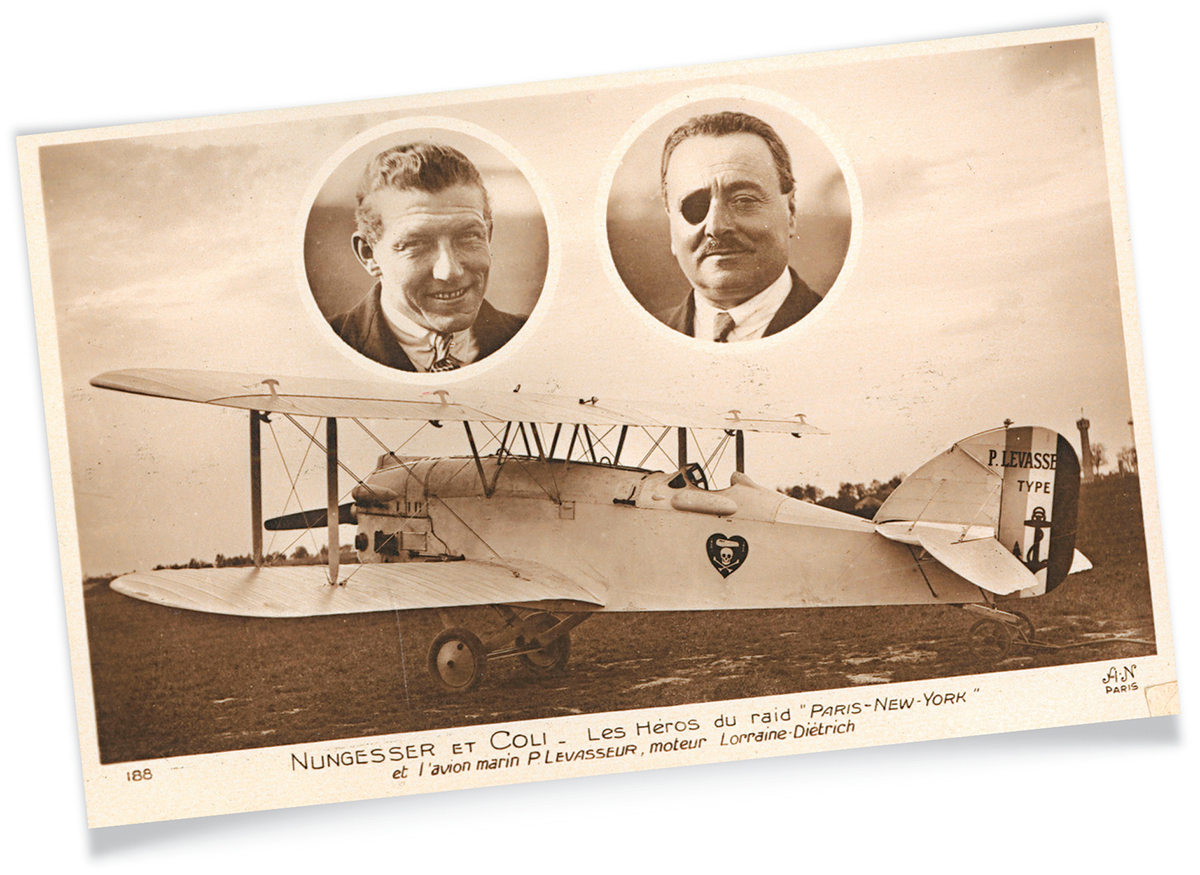

A 1927 postcard depicts the French biplane L’Oiseau Blanc, along with its copilots Charles Nungesser (left) and François Coli.

Harold Vining, a blueberry farmer in Maine, was outside chopping wood when he heard a roar in the sky. As it thundered closer, he wondered if it might be an airplane. It was May 9, 1927—11 days before Charles Lindbergh flew nonstop from New York to Paris—and airplanes were still a rarity in this sparsely populated coastal area. In fact, this was the first one Vining had ever heard. He looked to the sky in the direction of the rumble, trying to catch a glimpse, but the fog was too thick. He craned his neck, listening as the sound slowly faded into the distance.

Several miles away, a young couple also heard a plane that day. They were driving down the road and stopped their car to listen as it passed. Nearby, a woman was standing in her kitchen when she heard the unfamiliar grumble. A father and his 17-year-old son heard it, too. The boy thought it sounded like an old-fashioned cream separator floating through the sky.

A hermit named Anson Berry was fishing in his canoe on the south end of Round Lake when he caught the noise. He couldn’t see a plane but heard an engine sputtering overhead, followed by an unmistakable crash in the hills next to the lake. As the sun began to set, Berry returned to his campsite. It’s unknown whether anyone that day searched through the dense forest and steep inclines for wreckage.

In the decades since, legend has spread of a mysterious plane hiding deep in the woods. Dozens of hunters have reported seeing a large engine buried in a thicket beneath some trees, or covered in moss, but those are simply tales. The missing plane, the one Vining heard 90 years ago, is still out there.

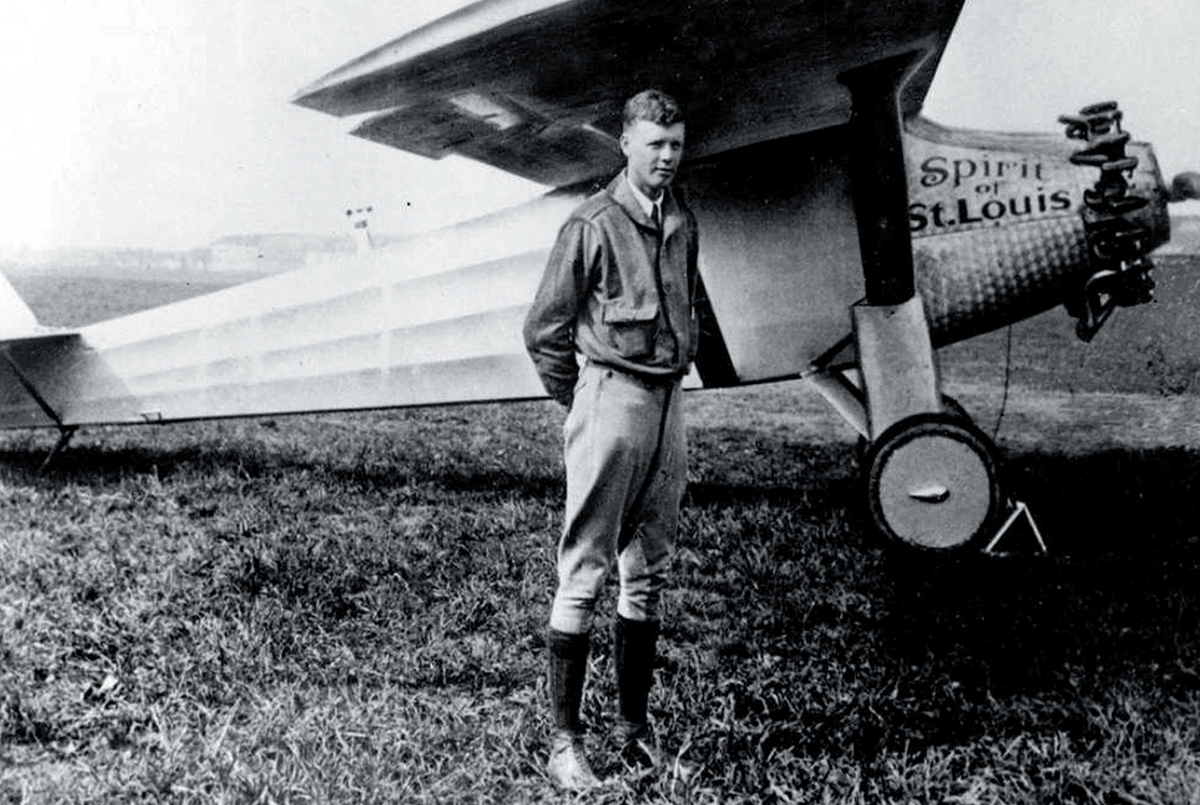

Charles A. Lindbergh is shown with his plane, Spirit of St. Louis, in 1927. / File Photo

When Lindbergh landed at Le Bourget Airport near Paris, the 25-year-old former airmail pilot immediately became one of the most famous people in the world. Until then, most travelers favored steamships and trains, considering airplanes akin to a death trap. By connecting New York City and the European continent in a single, nonstop flight, though, Lindbergh arguably changed that practically overnight. As soon as he touched down—winning a $25,000 prize for becoming the first Allied pilot to fly nonstop from New York to Paris, or vice versa—newspapers likened his historic voyage to the Wright brothers’ first flight in 1903. Suddenly, Americans wanted to fly. The number of airlines multiplied and the aviation industry soared. The story of Lindbergh and his plane, Spirit of St. Louis, became the stuff of legend and inspired generations of American aviation enthusiasts—including many of the pilots and aircraft designers who went on to help win World War II.

Suddenly a celebrity, Lindbergh gave speeches and participated in parades across the country, using his fame to promote the industry he loved. For a time, he was bigger than Humphrey Bogart and as beloved as Mickey Mouse. But Lindbergh’s famous flight did more than just cement his name in the annals of history: It forever cast a shadow on a pair of French pilots who would have permanently altered aviation and world history had they not disappeared inside what’s now considered one of the world’s most mythic missing planes.

As Lindbergh was gearing up to make his record-setting flight, the two Frenchmen were already several steps ahead of him. The first was Charles Nungesser, a rugged, charismatic fighter pilot during the First World War with dozens of air-combat victories to his name. Aided in no small part by his pale-blue eyes, a wry grin, and a scar across the side of his jaw from one of his many crashes, he became a postwar celebrity and heartthrob throughout France. He lived in a mansion, starred in a Hollywood movie, and even married a New York socialite: Consuelo Hatmaker, the younger half-sister of one of America’s richest heiresses at the time.

After a failed business venture and a public divorce, Nungesser’s star began to fade. By the end of 1926, his wife was a continent away and the flying ace was broke. A wild man obsessed with flight, particularly with the Franco-American aviation arms race taking place, Nungesser’s dream was to fly across the Atlantic. He knew he could recapture the limelight by winning the $25,000 prize for flying between Paris and New York.

Unlike Lindbergh, Nungesser did not fly solo. Alongside him was another hero from the war: François Coli, a captain more than 10 years his senior with a wife and children, who’d lost an eye in a crash. The French company Levasseur agreed to build them a new biplane. It had a wooden fuselage, so it could land and float in calm water, and was roughly 31 feet from end to end, with a massive engine and propeller. When the plane was completed in April of 1927, it was painted white so that it would be easier to find if the pilots crashed. They dubbed the plane L’Oiseau Blanc—the White Bird. Then Nungesser added a personal touch: his fighter pilot emblem—a skull and crossbones with a coffin and two candles, all inside a black heart.

The morning before takeoff at Le Bourget Airport (where Lindbergh would eventually land nearly two weeks later), a crowd of reporters, curious spectators, and celebrities including Josephine Baker, Maurice Chevalier, and future French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier gathered outside in the early-morning air. Ambulances sat parked along the runway. As the sun came up, a fire at a nearby factory gave the sky an eerie glow.

The pilots climbed into the plane wearing electrically heated leather flying suits. Nungesser stood, smiling and waving to the gathered masses. “We leave here broke, risking our lives,” he said. “If the Americans want my passport, I’ll turn back.” Coli added: “We’ve dumped everything, even our money.”

The White Bird started down the runway at 5:17 a.m. It lumbered forward, building up speed for nearly half a mile. The plane lifted off the ground, and then touched back down gently before climbing steadily into the air. The crowd went wild. As planned, the pilots jettisoned the wheels and landing gear to reduce weight. Escort planes followed the White Bird to the French coast, and then watched as it disappeared into the overcast morning sky.

The plotted route would take the plane northwest, over England and Ireland, then back southward over New England toward New York. The plan called for a water landing in front of the Statue of Liberty. The flight, from takeoff to touchdown, was expected to take roughly 40 hours. At approximately 7:15 a.m., a British submarine noted the plane over England. A few hours later it was spotted off the cliffs of Ireland. A French newspaper erroneously reported the next day that the duo had successfully landed. But the White Bird never arrived in New York.

Lindbergh, who nearly canceled his flight after learning that Nungesser had successfully taken off, wrote that the two Frenchmen had “vanished like midnight ghosts.”