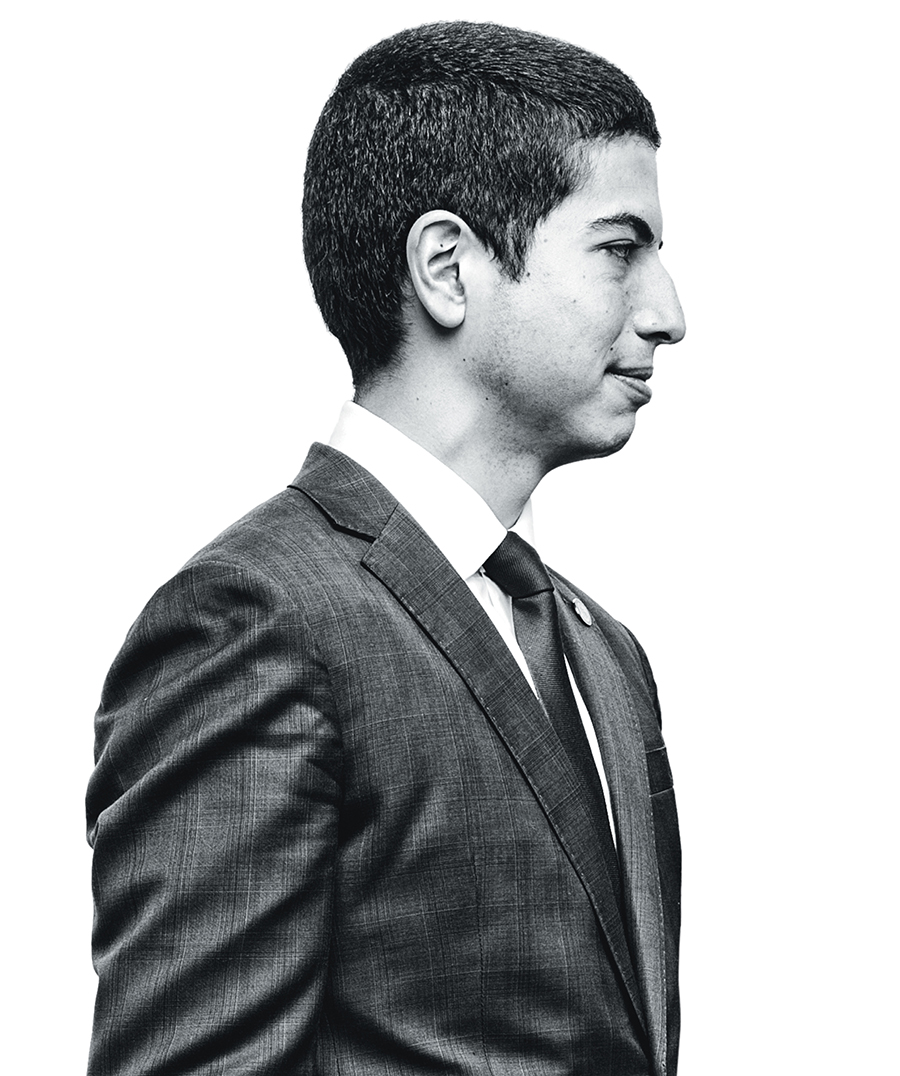

Koh, What a Life

Andover, Harvard, Mayor Marty Walsh’s number two, and all before the age of 30. Is there anything Dan Koh can’t do? As he steps out of the shadows and into the most fiercely contested congressional race in the state, we’re about to find out.

Photograph by Webb Chappell

Just after dusk on a Tuesday evening in January, Dan Arrigg Koh is talking to the owner of Hudson Appliance, a big guy with glasses named Arthur, as they’re standing in front of some top-of-the-line equipment in his showroom. Koh, a 33-year-old congressional hopeful dressed in his political team colors (blue tie, white shirt, navy jacket), leans against a massive stainless steel machine—the Samsung Family Hub 2.0—that’s reminiscent of the spooky black monolith at the beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey. It’s a fridge—no, it’s a smart fridge—equipped with a 21.5-inch touchscreen on the door and WiFi-enabled cameras that can live-stream the broccoli inside your vegetable crisper.

“What’s the biggest benefit of having the screen there?” Koh asks.

“Happy wife, happy life,” Arthur quips, in a friendly Rodney Dangerfield sort of way.

Koh lets out a short laugh, followed by an awkward I’m-not-sure-if-that-comment-was-politically-correct pause, prompting Arthur to make an addendum to his one-liner. “I’ll tell you what she likes about it,” he says, pointing to the screen (he and his wife own the model). “She puts all the recipes up there. She got rid of all her cookbooks and I said, ‘Thank God.’”

For the past hour, Koh, who’s clean-shaven and rocking a sporty crewcut, has been strolling the sidewalks of Hudson, a town of 20,000 in Middlesex County, along with a cadre of supporters. Hudson was once a mecca of shoe manufacturing in New England, and then struggled for decades in postindustrial squalor before going through a recent renaissance that has brought newfound energy to the place. Now it’s home to a micro-creamery, a locally sourced flatbread (don’t-call-it-pizza) joint, and the first notable “speakeasy” since Prohibition. All three storefronts had been vacant during the Great Recession. Today, Hudson is a destination for hipsters and townies alike, as well as stumping politicians.

“How has Amazon affected your business?” Koh asks, veering the conversation toward less colorful, more comfortable terrain after the awkward exchange.

“Me, well, it really hasn’t, because drones don’t carry refrigerators,” says Arthur, this time without any sarcasm. Arthur, a stalwart voice in Hudson’s business improvement district, equivocates. “It hasn’t affected us—yet. But they’ll figure out a way.”

Koh listens, politely looking for ways to relate. Mastering the art of making small talk with strangers, surrounded by the press, is no easy task, and he finds himself treading water. All around, people have local accents, but not Koh, even though he’s from the area. Instead, he speaks with a placeless articulation that gives him away as someone who has spent much of his life in rarified air. That is to say, ever since he built his first personal computer as a teenager, Koh has had a habit of making success look easy.

Photograph by Webb Chappell

The grandson and great-grandson of immigrants from Korea and Lebanon, Koh in many ways is the fulfillment of the American dream. Growing up, he watched his father rise from dermatology professor at Boston University to assistant secretary for health under President Barack Obama; he watched his mother, Claudia Arrigg, instill a strong moral compass in her children while managing to run a renowned ophthalmology practice in the Merrimack Valley. Koh himself graduated from Phillips Academy before earning degrees from Harvard College and Harvard Business School. He interned with then-Senator Ted Kennedy, because of course he did, and then worked as chief of staff for notorious diva Arianna Huffington in New York at the Huffington Post.

Then, at the ripe old age of 29, Koh took a job as Mayor Marty Walsh’s chief of staff, helping the former union leader manage the city’s $3 billion budget, broker deals with every power player in town, and ultimately win reelection last fall. Along the way, Koh married his grad school sweetheart, Amy Sennett, who serves as associate general counsel at Catalant, one of the fastest-growing startups in Boston. They stay remarkably fit by running marathons together (nearly 30 so far), and relocated back to Koh’s home district in 2017. In the battle to replace the retiring Niki Tsongas in the state’s third congressional district—which stretches from Haverhill to Gardner and includes such towns as Lawrence and Concord—he brings more money, national connections, and stamina to the race than any of the other candidates in an extremely crowded Democratic primary field. “Koh,” says Tufts political scientist Jeff Berry, “represents a high-tech, future-is-now profile.” And so far, he’s made it all look easy.

The coming months, however, are going to test how long he can keep it up. Koh’s early money and endorsements failed to scare off other challengers, teeing up a 13-way street fight for the rare open congressional seat. With the better part of a year left to go before the election, Koh’s opponents are already turning his image against him, labeling him as overconfident and an outsider. And as the clock ticks down on what is shaping up to be the fiercest contest in the state this political season, it’s only a matter of time before the gloves come off completely. When they do, Koh is going to have to show he’s more than just a work-hard, play-nice golden boy with an impressive résumé and the right connections. If he wants the people of the third district to punch his ticket to Washington, he will have to do something harder than collecting Harvard degrees or running marathons or even managing multibillion-dollar budgets: He’ll have to excite voters and make them like him.

Historically, Massachusetts’ third congressional district hasn’t been kind to rising hotshots, especially young Democrats. In 1972, the electorate kneecapped a 28-year-old John Kerry in his first campaign for Congress, after he’d prevailed in a crowded Democratic primary. Kerry faced an onslaught of negative attention in the local press. A couple of weeks before the general election, the Lowell Sun assailed him as a carpetbagger, writing, “Mr. Kerry is more interested in what the [District] can give him, namely a seat in Congress, than what he can give the [District].” When Kerry lost by nine points to Republican Paul Cronin, it was unclear for a while whether he’d be able to dust himself off and run again for public office.

Kerry wasn’t the first or the last up-and-comer to get his butt handed to him by voters in Lowell and Lawrence. Republicans ran the area for generations, and even now, although solidly Democratic, the district is centrist by Massachusetts standards—the kind of place where a wait-your-turn ethos has gripped electoral politics for ages. Like much of Massachusetts, the area has a long history of sending white guys with Irish roots to Washington: Niki Tsongas was only the second congresswoman from the district, and there’s never been a person of color to hold the Lowell seat. “This is a district,” says UMass Lowell political scientist John Cluverius, “where young upstart candidates have traditionally come to be shamed. That’s the history of this place. At the same time, the district is changing.”

How Koh chooses to tell his family story in a place that’s both a proud gateway for immigrants yet also wary of change remains a dilemma for his campaign. Koh isn’t white, but his family legacy in the area, which dates to the late 19th century, has a lot in common with the white Portuguese and Polish immigrants who also arrived there more than a century ago. “I feel an intense dedication and belief in this district in making people’s lives better, because it made my family’s life better,” Koh tells me in December, while driving me around the district in a white Honda CR-V. “It’s not only where I grew up, it’s where my family has been for over 100 years.”

His mother’s grandparents emigrated from Lebanon to Lawrence in the 1890s; his great-grandfather patented an invention for improving mill efficiency that ultimately provided the family with a solid financial base. Koh’s paternal grandfather, a diplomat from South Korea, settled in the United States in the 1960s following a military coup that forced him into political exile. Despite being a third-generation immigrant, Koh often expresses an affinity between his ancestors’ experience and the plight of immigrants today. “There are zero Koreans in Congress—zero,” he tells me. “Korean culture is one where there’s deference to authority, and risk-taking professions like elected official are not encouraged. [But] a lot of it has to do with institutional racism, too.” To further his point, one of the first stops he makes along our drive together is a single-family wooden home in Lawrence. “My grandfather Fred grew up and lived part of his life in this house and this neighborhood, a very humble neighborhood,” Koh says. “They came from Lebanon, now Syria. I like to remind people that in today’s world they’d be stopped at the border.”

Photograph by Webb Chappell

As honed as his telling of his family’s origin story may be, hitting all the right notes of perseverance and hard-won success, Koh staggers a bit when he tries to talk about what he personally had to overcome. His parents, both doctors, provided Koh and his siblings a stable home life and all the tools to succeed. Today, older brother Steven teaches law at Columbia and younger sister Katie is a doctor at Mass General. Koh doesn’t duck his privileged upbringing, but he also doesn’t like to talk about it. “I’m proud of my family and their story here,” he tells me. “I know that there will be criticism, but I’ll leave the judgment to other people.”

When Koh does talk about what he struggled with on his impressive rise, he recalls having ADHD as a kid, and the stigma and fear of not succeeding that went along with it. On its own, it can sound like a device to round out the hero’s arc of his political narrative. But with a family as high-achieving as his, it can also be seen as a rare moment of vulnerability. What’s clear either way, though, is that failure was never really an option.

When Koh appeared as a guest on the Growth Show, a podcast produced by the Cambridge tech company HubSpot, in 2015, he publicly danced around what everyone in town long suspected: He wasn’t going to remain a number two forever.

The Growth Show: Can you see yourself moving from behind the scenes to in front of the scenes and shaking hands and running for office?

Koh: [Politely laughs.] Well, you know, a lot of people who run for office try to say, “Oh, I never thought of myself in those shoes.” That’s not true, at least not in my opinion. I just want to be honest with people. I’ve always thought of public service as a really exciting opportunity, but…it will have to be a good aligning of stars for that to happen.

The Growth Show: Nice dodge.

The leap from chief of staff to candidate is trickier than it sounds. While quintessential go-getters, chiefs of staff are not necessarily the charismatic visionaries that voters latch onto. The degree of humility it takes to do the job well can, in the limelight of a campaign forum, come across as dull, wonky, or even weak. In Boston’s history, though the list of mayoral chiefs of staff is long on savvy political veterans and City Hall lifers, it’s not a traditional stop on the way to national office. As far as I can tell, Barney Frank, who took the job as Mayor Kevin White’s first chief of staff in 1968, is the last person to have held the job before later winning a seat in Congress. (You also have to go back to Frank to find someone younger than Koh at a mayor’s side—Frank was 27 to Koh’s 29.) Koh was a natural in the job. “With the chief of staff,” Mayor Marty Walsh tells me, “it’s all about finding common ground. Dan was a master at making everyone feel like they got a win and their voices were heard.”

Even though Koh is working hard to step out of his mentor’s shadow, he’s still Walsh’s guy. After driving me around to several of his old haunts, Koh pulls over at Perfecto’s Caffé, a tiny breakfast shop off the main drag in Andover. It’s mid-December, and Mariah Carey is playing on the speaker overhead. Koh orders a Diet Coke. “They’ve got some pretty good carols on here,” he says. “I almost want to start dancing.” He doesn’t. But some alchemy of caffeine and Christmas spirit has suddenly made Koh nostalgic: He starts scrolling through the photos on his phone and lands on a picture of Walsh. “I get emotional when I think about him,” Koh says. “He was so there for me. I can’t tell you how many times he’s called me late at night with an idea. I mean, he was a groomsman in my wedding.” Koh hands me his iPhone. There’s a shot of Walsh, wearing a tuxedo and squeezing out his best steely Zoolander face for the camera.

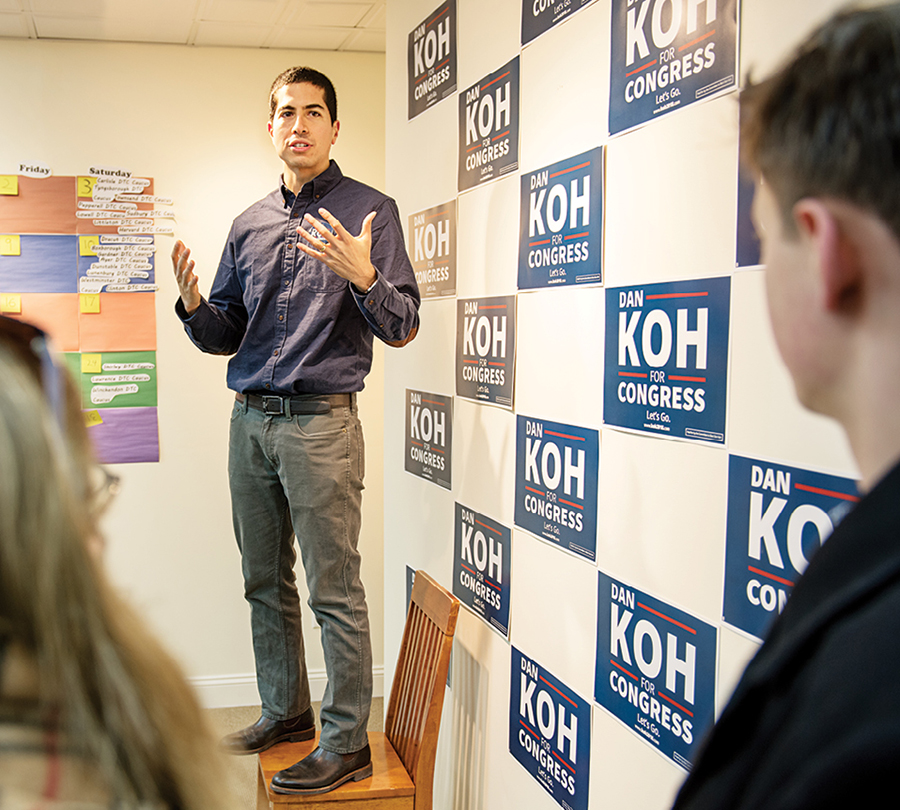

Despite being a first-time candidate, Koh is backed by a deep bench of political heavyweights. At an event in early February, Koh works the room alongside his former boss Marty Walsh and his wife, Amy Sennett. / Photograph by Webb Chappell

Ever Walsh’s disciple, Koh is pitching a vision straight out of his days at City Hall: a platform that blends the efficiency of market economics with a constituent-first mentality. On the campaign trail, Koh emphasizes his experience with public projects that required significant boardroom wrangling, including some of the more notable dealings in Walsh’s first term, such as bringing General Electric to Boston and coordinating the failed Olympic 2024 bid. He also hits on less-publicized agenda items, including the city’s adoption of accountability measures such as CityScore, which collects real-time data and delivers officials information about the overall health of the city. To hear him tell it, this fully formed nuts-and-bolts brand of politics will serve the third district better than a slick-sounding plan that doesn’t come with blueprints attached. “You learn about the intricacies of real estate development and how a dilapidated building becomes economically viable again,” Koh says. “It’s not just incentives. It’s good cooperation between people to get things done.”

It’s not exactly the kind of stuff you want to slap on a bumper sticker, but that is both Koh’s greatest strength and most pointed weakness. He’s not just willing to go into the weeds; he seemingly prefers to. In that spirit, he’s crafted a progressive, if measured, set of policies to run on. Most are staples for anyone generally in favor of the social safety net: universal healthcare coverage with a public option, more money to combat the opioid crisis, universal pre-K and strong public education, stronger background checks for gun purchases and an assault weapons ban, paid family leave, and support for developing renewable energy sources. He tells me he would have opposed the recent tax overhaul and is for the preservation of the Affordable Care Act, with tweaks. It’s not a platform that’s going to set anyone’s hair on fire—in fact, it’s the kind of boilerplate list that Democrats are running on all over the country right now. But Koh might not need to prove he’s a fire-breather to win. “I don’t see an Elizabeth Warren in the field,” Berry says. In a moment when national politics is lurching from one norm-busting crisis to another, electing a guy who is basically promising to do his homework is not without its charms.

During our time together, Koh often returns to not only bread-and-butter economic issues, but also wonkier ones like the boundless potential of self-driving cars. “When you think about California,” he says as we’re driving through Lawrence, “Cupertino is an hour and a half from downtown San Francisco, yet no one would claim that they’re struggling for talent. Companies don’t think of a place like this. Public transportation is relatively inconsistent. But you can imagine how beautiful and economically appealing it would be for a big company with good jobs at all class levels to come to a city like this and provide jobs and provide a real anchor for the community. I think the opportunity is here.”

But do people in the third really want to hear about self-driving cars? Perhaps not at first. “In a vacuum, nobody cares about automation,” Koh acknowledges. “But when you think about it in the context of jobs and middle-class prosperity, it can be a huge mistake not to proactively plan for these kinds of things. People care about their access to well-paying jobs.”

Koh may be running as Walsh’s protégé, but he’s got a very different demeanor than his former boss. In the mayoral race to replace Tom Menino, Walsh relied heavily on his everyman appeal and buoyant energy. Koh, meanwhile, seems determined to pitch his core competencies more than charisma. “I had the opportunity to spend four years as the number two guy at a $3 billion organization with 18,000 employees,” he says, giving me his pitch to voters. “We had one of the most prosperous stretches in Boston history. Not [the most prosperous] for everybody, and that’s a concern, but the mayor was just reelected by 32 points, so they obviously think we were doing a good job.”

In the race for Congress, Koh is unsurprisingly off to a fast start. He raised $1.6 million, much of it through large individual contributions, in a mere four months, which ranks him as one of the top fundraisers nationally for the 2018 midterms. Koh is also surrounded by a who’s who of allies and supporters. Political wizard Doug Rubin, who helped get Elizabeth Warren and Joe Kennedy elected, advises his campaign. Obama’s former chief strategist, David Axelrod, introduced him at a fundraiser in Chicago. Former Red Sox CEO Larry Lucchino happily handed over the maximum allowable contribution, $2,700, to Koh’s campaign. Still, the countless connections Koh has made as Walsh’s right-hand man, especially among Boston’s rich and powerful, have put a target on his back.

At least that’s what I’m repeatedly told by Koh’s opponents, including state Senator Barbara L’Italien—who a month after my impromptu lunch at Perfecto’s with Koh suggests we meet at the same place. “I don’t think that Dan or Marty understands how it plays to walk in with a load of cash, having been gone almost 15 years out of this district, to come back and wave around this money thinking that he’s going to be the winner,” L’Italien says, right out of the gate. “I don’t see that playing well in this district.”

Campaign money, of course, is only as good as its use to defeat the field. Since Koh announced the meteoric totals from his first round of fundraising, the number of declared Democratic candidates has more than doubled, and at the time of publication stands at 13. “One of the reasons you want to raise money early,” says Cluverius, the UMass Lowell professor, “is you want to scare a lot of candidates away. [Koh’s] fundraising is not having the same effect that I would expect it to have.”

L’Italien believes one of the reasons Koh and his team aren’t running away with the race is their lack of political clout in the district. “They need that money to catch up to me in terms of name recognition,” she says. By simply turning out a high number of voters in the five communities located within her own state legislative district, she argues, “which represent approximately 30 percent of the primary vote,” she has a substantial base to build off.

If L’Italien or anyone else—fellow candidates include state Representative Juana Matias of Lawrence; former congressional aide Lori Trahan of Lowell; and political neophyte Beej Das, a good-cause hotelier—has a chance at defeating Koh, however, they’ll need some luck. That’s because Koh doesn’t have to outright win this race as much as not lose it. In the last midterm election, there were roughly 230,000 votes cast in the district. This time, with so many hopefuls still campaigning, “I think this will be a race with a lot of candidates lopping off different pieces of the district,” Cluverius says. “Which means that if you can run a solid second or third everywhere, you can have a path to victory.”

On a cold sunday afternoon in January, Koh is decked out in a thermal top, black leggings, and turquoise sneakers from New Balance, a company based in the district, he points out. We’re running a 5.5-mile loop from his apartment on the outskirts of town, which is shorter than the half-marathon Koh usually runs on weekends. The sidewalks are caked with snow from the bomb cyclone, so we’re mostly running in the road while cars rumble by us. “You’ve just stumbled upon the most confusing part of the town of Andover,” Koh tells me. “There’s Lincoln Street and Lincoln Circle. It’s a huge point of contention. People who’ve been here for 20 years don’t know the difference.”

To be honest, it’s a boring piece of trivia—the sort of small-ball civic marginalia most people would never bother to sort out. It’s also the kind of thing Koh seems to get a huge kick out of knowing. While he may lack the bombast of a Barney Frank and the down-to-earth frankness of a Marty Walsh, Koh is selling his own image as a tireless worker who isn’t afraid to grind it out. In the slickly produced video that launched his campaign, Koh’s voiceover repeated “Do the work” like a mantra (though his official campaign slogan is “Let’s Go”). Even at the start of our run together, my attempts to discuss the Pats’ pre–Super Bowl drama are instantly batted down. “You know, I worked for the Krafts,” Koh says as if to warn me that his answer will be entirely diplomatic. Before long, though, Koh begins to loosen up. He mentions Michael Wolff’s book about Donald Trump, Fire and Fury, and grows more animated. “The biggest problem with Washington these days is a lack of urgency,” he says to me. “We can’t just say we’re going to resist the Trump administration. We have to say we’re going to resist it with these policies and programs.” It’s not the sexiest line of all time, but it’s probably the kind of thing more members of Congress should be thinking about.

Koh appears to be exactly the sort of candidate so many Americans have been clamoring for: young, enthusiastic, bright, a minority. He’s part of a generation who came of age during Barack Obama’s out-of-nowhere rise and vows to advance Obama’s vision of America, oppose the Trump administration, and fight for the middle class.

Of course, none of that could matter in September when voters go to the polls. We’re living in a time when unconventional politicians are in vogue. By the time the third district is hosting candidate forums and debates, let’s say one constituent makes Koh go on the record about whether he’d vote to impeach Trump, and Koh, playing it safe, waffles just slightly. That could be all anyone cares about. “I’ve been doing this for a long time, 25 years, so you’d think I’ve seen everything,” Doug Rubin says. “But this is an environment that’s different. You could lay out the best campaign plan, but the president wakes up tomorrow and says something, and suddenly everybody is focused on that issue.”

To combat this unpredictability, Koh is sticking to what’s worked in the past: prepare, smile, and stay cool. Despite being the odds-on frontrunner, though, he knows better than anyone that to pull out a win, he’ll need to prove he’s not a carpetbagger in a district that’s sunk bigger politicians than him. “I’m just taking it day by day,” he says, “and putting my best foot forward.”

After all, winning is simply what Koh does.