Black Women Take the Spotlight in the ICA’s “We Wanted a Revolution”

Art by Faith Ringgold, Betye Saar, Carrie Mae Weems, and more challenges perceptions of second wave feminism and the black arts movement.

Faith Ringgold, For the Women’s House, 1971. Oil on canvas, 96 x 96 inches (243.8 x 243.8 cm). Courtesy of Rose M. Singer Center, Rikers Island Correctional Center. © 2017 Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965-85” is organized by the Brooklyn Museum.

The phrase “second wave feminism” often calls up an image of young white women burning their bras, led by Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem in a Playboy bunny outfit. “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965-85,” which opened June 27 at the Institute of Contemporary Art, wants to change that.

Originally compiled and curated by the Brooklyn Museum, “We Wanted a Revolution” tells the story of the black female artists who were excluded from both white feminism and the male-dominated black art world. It features works ranging from paintings and sculpture to photo and video, accompanied by original notes and documents by and between artists.

The Brooklyn Museum is home to Judy Chicago’s famed second wave feminist work “The Dinner Party,” which imagines feminist icons from throughout history finally taking their seat at the table, yet includes only one black woman (Sojourner Truth) out of 39 place settings. “We Wanted a Revolution” was originally conceived as a way to expand museumgoers’ perception and definition of feminism and female artists.

“This exhibit is a landmark in both contemporary and historic art,” says assistant curator Jessica Hong. “It’s shedding light on a period of history that often goes overlooked. We felt early on, even before we saw it in Brooklyn, that we had to bring it to the ICA.”

In keeping with the ICA’s commitment to telling underrepresented stories, “We Wanted a Revolution” focuses on the stories of women who are often overlooked in the retelling of second wave feminism stories. Unwelcome in the mainstream second wave feminist movement, black female artists formed their own coalition.

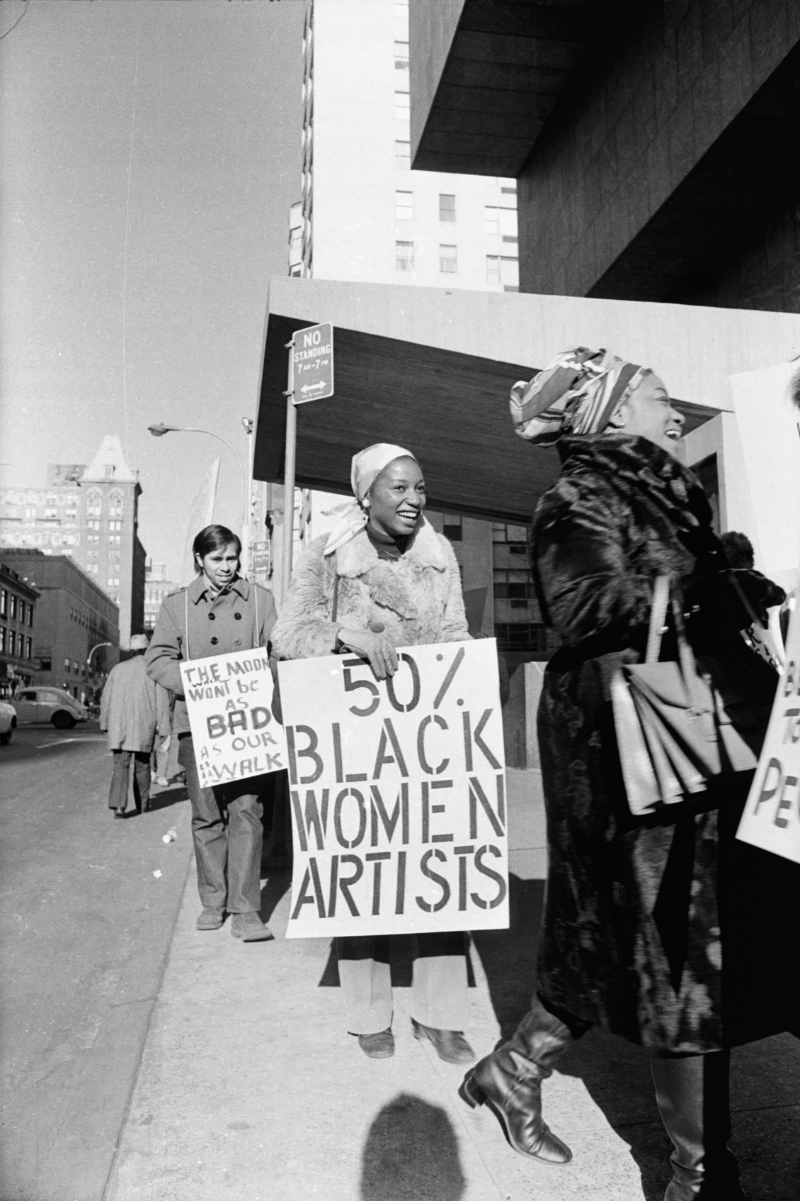

Artists Kay Brown, Dindga McCannon, and Faith Ringgold, whose “For the Woman’s House” (1971) opens the exhibit, founded the black female artists’ collective Where We At in New York with the goal of self-empowerment and reclaiming the representation of their own bodies and struggles.

Jan van Raay, Faith Ringgold (right) and Michele Wallace (middle) at Art Workers Coalition Protest, Whitney Museum, 1971. Courtesy the artist, Portland, OR, 305-37. © Jan van Raay. “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965-85” is organized by the Brooklyn Museum.

“They gathered to discuss the difficulties they faced as black women artists—they were excluded from the white and male art worlds,” Hong says. “They had to juggle and fight all these different expectations of being wives and mothers and black women. They became each others’ support system, both personally and professionally.”

Many of the artists represented in “We Wanted a Revolution” found a voice in Where We At, including Carrie Mae Weems, Betye Saar, and its three founders.

The group, which announced its arrival with the self-titled exhibit “Where We At: Black Women Artists: 1971,” grew until merging with the larger Black Arts Movement, the artists’ branch of the Black Power movement, in the mid-1970s. Spiral, another group of mostly male black artists, also joined BAM as the black power movement gained strength.

Spiral, fronted by Romare Bearden and Hale Woodruff, accepted only one female artist, Emma Amos, in its three active years. Her work, which is featured in “We Wanted a Revolution,” had to be reviewed before she was allowed into the group, a process none of its male members had to undergo.

Although Spiral predates the years covered by the exhibit, Hong notes that its work is essential to understanding what came after and how the black artists’ movement developed over time.

“Photography unfolds and becomes more prevalent throughout the exhibit,” she says. “It became easier to document their daily lives and protests, and record and preserve performance art.”

Carrie Mae Weems, Family Reunion, 1978-84. Gelatin silver print, 30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm). Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Carrie Mae Weems. “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965-85” is organized by the Brooklyn Museum.

The exhibition highlights the personal lives of the artists in conjunction with their work by showing original correspondences, notes and archival material alongside the art. The original curators at the Brooklyn Museum found much of their material at the Billops-Hatch Collection at Emory University and worked directly with the artists themselves to tell their collective stories, since most of them are still alive and many are still producing work.

Some pieces required more excavation than others, including some that hadn’t been on view for many years. A few, including Saar’s “Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Cocktail,” made their museum debut at the Brooklyn Museum’s showing, despite being created decades ago.

“We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965-85” will be on view through September 30, 2018 at the Institute of Contemporary Art, 25 Harbor Shore Drive, Boston, icaboston.org.