The Case of the Heart That Wouldn’t Tick Right

Can your hair texture determine your predisposition for a genetic heart disorder? In this case, diagnosed by Dr. Neal Lakdawala of Brigham and Women's, it can.

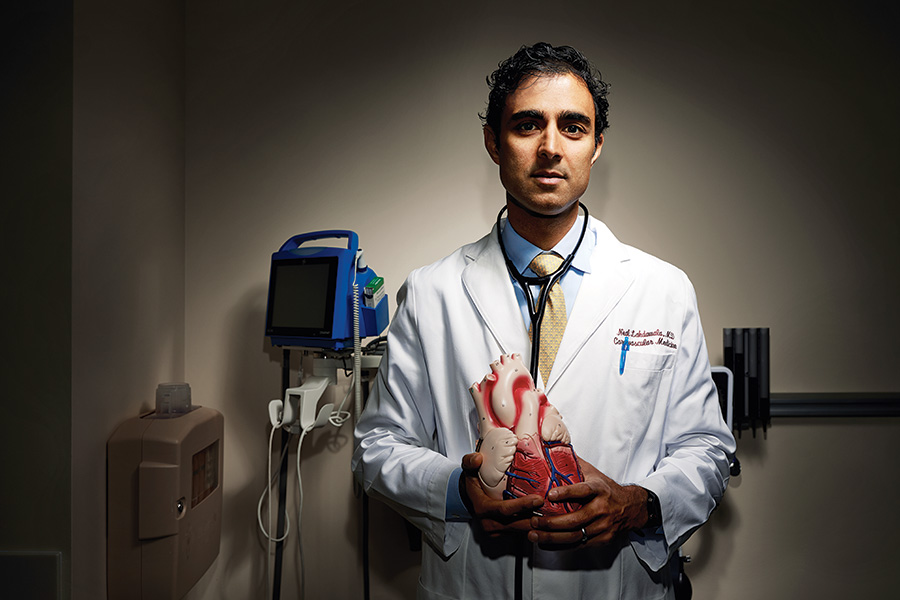

Ventricular specialist Neal Lakdawala, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital. / Photo by Ken Richardson

In nursing school, you get used to playing the patient while other students take your blood pressure and check your heart rate. When Elisabeth’s classmate listened in on her heart, though, the role-playing got serious. In fact, the nurse in training wondered if she was hearing correctly. She called over their instructor at Brockton Hospital, who placed the stethoscope on Elisabeth’s chest again. “You should go see your doctor,” Elisabeth recalls the instructor saying. “You have an irregular heartbeat.”

Elisabeth wasn’t terribly worried. After all, nursing school was stressful, and Red Bull energy drinks had been a mainstay of her diet. Her doctor wasn’t sure if the pressure of school was causing the arrythmia, but they both agreed to treat her with beta blockers and monitor the situation. Elisabeth was healthy otherwise, and felt like her heart had always been a little bit fluttery—“like a boombox,” she says.

Things changed about three years later, when Elisabeth was treating a patient with heart problems in North Carolina, where she had recently moved with her husband. A young woman with no prior health problems came in with postpartum cardiomyopathy, a condition in which the heart fails to work after giving birth. The young mother was desperate to care for her baby and desperate to live, and her suffering haunted Elisabeth, who was feeling ready to have her own children. I don’t know what’s wrong with me, she thought. Will going through a pregnancy put extra stress on my heart?

Elisabeth decided right then that she would not carry a child until she discovered what was amiss. On her quest, she saw many doctors, to no avail. She even allowed doctors to cauterize her heart muscle in hopes of stopping the irregular beats, but it didn’t help. Increasingly worried that every palpitation could lead to sudden death, she expressed her fears to her local cardiologist and was told of a ventricular specialist in Boston. Elisabeth immediately booked a flight home.

Inside the Brigham and Women’s office of Neal Lakdawala, Elisabeth rattled off her medical history. Then the doctor surprised her with a series of strange questions. “Is that the natural texture of your hair?” Elisabeth remembers him asking. She and her husband both looked at him like he was crazy. “Just bear with me,” he said. “Do you ever get calluses on your hands?” Yes, in fact, she had suffered from terrible calluses since she was a young girl and often shaved or pumiced them off. But how did he know?

In fact, Lakdawala was working on a hunch that Elisabeth could have a condition called arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. This unusual genetic mutation—which causes an electrical malfunction of the heart, and can be deadly if left untreated—is found most often in people with dark-brown, curly hair and callused hands and feet. And as it turned out, Lakdawala was right: A blood sample sent out for genetic testing came back positive.

With an official diagnosis, Elisabeth was able to move forward with her life. She had a defibrillator implanted to act as an insurance policy: If her heartbeats increase or become dangerously irregular, the device will shock her heart back to a normal rhythm. But most significantly, she decided to make sure this condition ended with her. In 2019, Elisabeth underwent in vitro fertilization so she could prevent the gene associated with her heart disorder from being passed on to her future child. She is now pregnant and no longer living in fear of the unknown.