Boston’s Middle Class Is Doomed

Admitting there’s a problem is the first step toward fixing it—if the residents actually want to, that is.

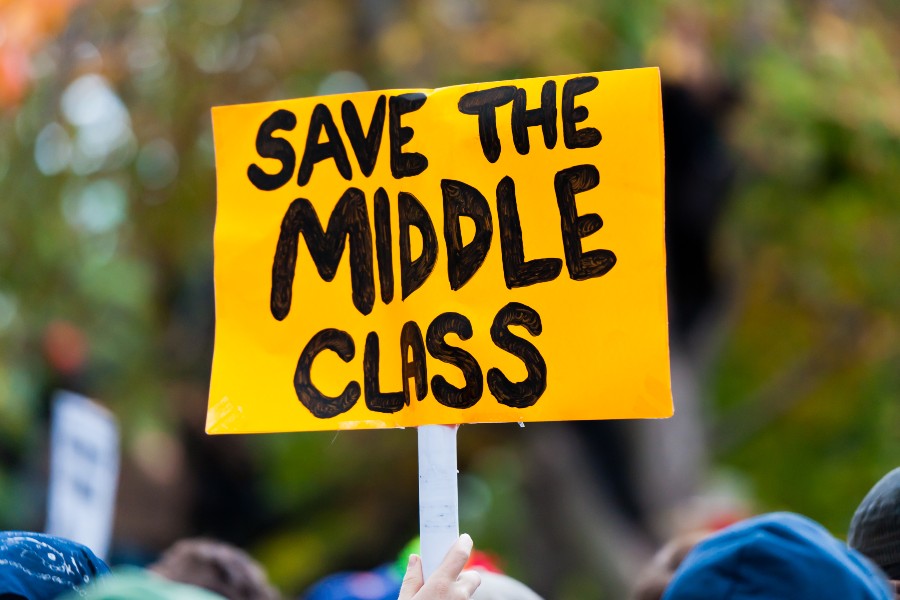

/ Photo via Getty Images/ jentakespictures

Like a guy picking up his favorite T-shirt from college and thinking, “Yeah, I can still rock that” despite the thirty pounds he’s gained since then (yes, it’s me), Boston’s self-image is stuck in an earlier era. Despite the luxury-condo developments and tech sector nouveau riche that have become today’s norm, we often still talk about our city as having a largely well-to-do middle-class that is enjoying the upswing of an economic boom. In moments of reverie, we even fall into the trap imagining our city through a distinctly Wahlbergian lens—populated by flinty firemen, steely cops, and other triple-decka’ dwellers who run on Dunkin’s and good ol’ common sense. Never mind the fact that nobody in The Departed could actually afford to live here anymore.

It’s not breaking news that Boston’s middle-class is in decline. Residents have been talking about that for a long time, but recently the Globe published two statistics from the Boston Foundation side by side that tell you pretty much everything you need to know about the trajectory of the city: There are 10,000 fewer school age kids living here than there were in the year 2000, and almost 1,000 more households with incomes of $1 million and up than there were in 2015. In addition, Boston has the seventh highest income inequality among major U.S. cities, according to a recent Brookings Institution analysis.

Maybe the reason this is happening is because we haven’t been honest with ourselves about the city’s current situation: Boston isn’t becoming a place where rich people are thriving and middle-class people—particularly those with kids—are unable to build their lives. Rather, as anyone still desperately clinging on to city life can tell you, the middle-class dream in Boston is not only dead and buried, but its friends and family don’t even visit the grave anymore.

While not every middle-class family has decamped for the burbs, or Worcester, or wherever it is they’re supposed to go, the future seems clear: Sooner or later, they’re not going to be able to stay. It’s a matter of simple math. When the real estate firm Unison crunched the numbers on how long it would take a middle-class household earning a median income while squirrelling away 5 percent per year to save for a down payment on a first home here, it found that it would take 30 years, assuming they bought a median priced home. In other words, if you started saving in your mid-20s, you’d move in when you were in your fifties. (Remember to lift with the knees, old man.)

This situation has been a long time in the making. Even though the city is booming, both in terms of its economy and its population growth, Boston has been steadily losing families with kids, says Luc Schuster, Director of Boston Indicators, the research center at the Boston Foundation that provided the statistic used in the Globe story. Despite adding more than 130,000 residents since 1980, when Boston’s population bottomed out, the city has 6,000 fewer school-age kids. More specifically, when middle- and high-income families have school age kids, they tend to flee. Part of this is the economic crunch of affording a higher rent or mortgage for a bigger home. Some of it, though, is concerns over the quality of the public schools.

We know all of this, of course, and yet every time we hear it, in some new and horrible way, the news is still a punch in the gut. “Boston is breaking my heart,” tweeted Brendan Halpin, a writer in his 50s, after reading the Globe story about the decline of school-age kids in the city. He moved to Somerville in 1991 and then to Boston two years later, but suddenly feels like an alien in his own town. “In big and small ways, Boston—its leadership, its architecture, its public spaces—is telling me I’m no longer welcome here because I’m not rich.”

Don’t get me wrong, I realize that the things one loves about a city are often suddenly replaced by new things you may hate. It’s a story as old as time. But here in Boston, the middle class has always been part of our identity and soul. Plus, says Schuster, when a city loses its middle-class, it also loses “some of the basic fabric of what it means to be a community. There are many ways in which Boston’s gotten a lot better in recent years, but I think one way in which we’re moving in the wrong direction is that Boston used to be a city of neighborhoods—the sort with middle class families. And I think that that hollowing out is a troubling trend.”

Aggressive, innovative change is probably the only thing that can save the city’s middle class. Mayor Marty Walsh’s administration is planning to beef up spending on schools by $100 million over the next three years and has made a big push to build more housing, even if much of it will be smaller units, all of which is a great start. The suburbs, on the other hand, are hardly building at all and need to step up and do their part, and in order to really make a dent, we probably need to think much bigger and make some hard choices when it comes to who the city is ultimately for.

At this point in time, there is no easy fix. But is there still hope—through innovative urban planning, or even voodoo or witchcraft—to bring the middle class back to Boston? Honestly, I don’t know. I do, however, believe that it won’t happen unless we face facts about just how bleak our city’s future appears to be without them. And if you want to live in a city where every last neighborhood feels like the Seaport, well, what can I say? You can have it.