Robert DeLeo Is King of the Hill

After generations of iron-fisted leadership on Beacon Hill, the winds of change are beginning to blow. Just don’t tell that to House Speaker DeLeo.

Photo illustration by C.J. Burton

If ever there was a moment when the opaque inner workings of Robert DeLeo’s House of Representatives were revealed for all to see, it was at the tail end of a marathon day of voting in January 2019. The exhaustion filling the room that Wednesday was undeniable. After nearly six hours of voting, a member of the Democratic leadership announced that there would be three minutes for members to cast their ballots on an amendment that had just been presented. As the din of conversation filled the chamber, a red light signifying a nay vote came alive beside DeLeo’s name on the giant scoreboard that hangs in the front chamber, displaying how each representative votes for all to see. Immediately after his vote was recorded, the board lit up like a Christmas tree as red lights appeared next to the names of 63 Democratic members.

Moments later, though, a small-scale kerfuffle erupted after the proceedings’ presiding House member, who had registered DeLeo’s no vote, realized he’d made an error and it should have been a yes. “It’s a yes? Switch ’em, yes, yes, yes, yes,” the presiding member said, not realizing his instructions were being caught on an open mike.

DeLeo’s light quickly switched from red to green—and within seconds, so, too, did the lights of all 63 members who moments before had voted no. So much for understanding the content of the amendment or voting with their conscience. Instead, here were more than five dozen Democratic members following their leader, this way and that, as if guided by remote control.

As remarkable as the whole scene appeared, though, about the only truly exceptional aspect of the incident was that everyone could see the members’ blind allegiance in real time. As it turns out, this is precisely how things work in the House of DeLeo.

At press time, DeLeo, who declined to be interviewed for this article, was set to become the longest-serving speaker of the House in Massachusetts. It isn’t just the length of his rule that has broken records, though, but its strength. DeLeo has managed to secure a dizzying degree of loyalty from his members, has whittled floor debates down to next to nothing, and has all but eliminated dissent among representatives of his party. For his supporters, this is evidence of a masterful leader, a consummate consensus-seeker, and an all-around good guy who excels at wrangling and cajoling 125 Democratic members with disparate interests into line.

Yet as DeLeo enters the home stretch of his unprecedented sixth term, current and former Democratic members, along with Beacon Hill insiders, are increasingly challenging this long-standing narrative. DeLeo may be a chummy, unassuming guy from Winthrop, they say, but behind closed doors he rules ruthlessly—favoring those who follow him and destroying those who dare to defy him. “He is a king and the House is his kingdom,” Representative Russell Holmes says. “He appoints his dukes and duchesses, and they go enacting his will in the building.”

That might have been par for the course last century, when the three speakers before DeLeo employed versions of the same autocratic style of leadership. In 2020, though, the world of politics is moving in the opposite direction from the secretive, overwhelmingly white and male leadership structure that still maintains a grip on the House. Boston City Council has almost completely transformed from old-machine pols to diverse activist agitators. The state’s congressional delegation now includes a woman of color, Cambridge has a Muslim female mayor, and the Suffolk County district attorney is a black woman with the politics of a public defender. The last Boston City Council president advocated for an independent inspector general for City Hall. Everywhere you look, in fact, our political class is pushing to reform musty old institutions and promote inclusiveness and transparency.

In other words, this brave new world of local politics has little need, or want, for a speaker like DeLeo, and the House he built is increasingly looking like an anachronistic living-history museum. “A really big change has occurred in terms of governance in the past decade in which things have become democratized and leaderless,” says a Massachusetts political staffer who wished to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal. The staffer adds that while this process has happened during DeLeo’s leadership, it has not infiltrated the House, where “the only path to power is through DeLeo.”

No one other than DeLeo himself is entirely sure when he will step down. Some of his loyalists are queuing up to succeed him, and chances are one of them will ultimately prevail. But there are already signs that his successor won’t be able to keep the changing world of Boston politics at bay much longer. And when DeLeo does go, we likely won’t remember him just as the longest-serving speaker in state history, but as the last of his kind.

In 2020, the world of politics is moving in the opposite direction from the secretive, overwhelmingly white and male leadership structure that still maintains a grip on the house.

Aside from DeLeo’s unshakable belief in the virtues of top-down rule, it is sometimes hard to pin down his politics or discern whether he has much of an ideology at all—unless, that is, being from Winthrop counts as one. The speaker has spent nearly his entire life on the peninsula, which juts into Boston Harbor and is firmly connected to the mainland and the city, even as it remains a world apart. It’s a throwback community of 18,000 people, with single-family houses on neatly manicured, postage-stamp-size lots and an old town square. But what Winthrop lacks says almost more: It has few chain stores, very few people of color (the town was nearly 95 percent white, by the most recent Census estimates), and even fewer outsiders.

DeLeo could never be called an outsider. Born in East Boston, where his father worked as a maitre d’ for a restaurant at Suffolk Downs, DeLeo moved with his family to Winthrop when he was eight years old, settling into a small home on a corner lot where he lives to this day. As one of several kids from neighboring areas who were accepted under Boston Latin’s eligibility rules at the time, he began making a daily 9-mile trek to school in the big city as a teenager. The youngest in his class, DeLeo nonetheless thrived, recalls classmate Larry DiCara, becoming a star baseball player and accumulating friends everywhere he went.

Northeastern University and Suffolk Law School followed. Rather than join Boston’s high-powered law community after graduation, though, DeLeo stayed true to his roots and opened a law practice in nearby Revere, got married, and started a family. By 1977, however, he began dabbling in electoral politics, becoming a Winthrop town meeting member and then a selectman the following year. But DeLeo had his eyes on an even bigger prize. In 1990, he was elected to the House at 40 years old.

As a state rep, DeLeo ardently defended his district’s interests, whether he was fighting to secure a controversial Logan Airport expansion that would provide jobs to his constituents, or keeping watch over the ever-encroaching Massachusetts Water Resources Authority operation of the Deer Island wastewater treatment plant. What drove him, says Jim Eisenberg, DeLeo’s former chief of staff, was “wanting to help out the blue-collar worker…he connects with folks who maybe didn’t get a college degree.” Or as DiCara puts it, “He’s grounded. His understanding of John Q. Public is not because he read it in a book.”

While DeLeo was fighting for Winthrop’s everyman, though, the culture inside the House was changing around him—and slowly shaping him into the leader he has become today. His election came at a pivotal moment in State House history: A six-year experiment in openness and decentralization under Speaker George Keverian had just come to a close and the new speaker, Charles Flaherty, was eager to do things a little differently. His first order of business? Shutting the blinds in the chamber as tightly as possible. He concentrated power and took to conducting business behind closed doors. Ultimately, though, the lack of transparency caught up with him: After serving three terms as speaker, Flaherty pleaded guilty to tax evasion and resigned.

Things didn’t get much better from there. The next speaker, Tom Finneran, not only continued Flaherty’s iron-fisted governing style, but also bumped it up a notch, tossing out term limits for the speaker in a move that seemed ripped out of a South American dictator’s playbook. Coincidentally, Finneran was someone DeLeo knew well from when they were both students at Boston Latin. Now Finneran was DeLeo’s teacher, showing him how to run a centralized House and ultimately laying the foundation for DeLeo’s ascent to power.

DeLeo’s first big promotion in the House, in fact, came courtesy of Finneran, who named him chair of the Committee on Bills in the Third Reading after Finneran took over in 1996. If that doesn’t sound like a flashy post, that’s because it isn’t. As a way station for the vast majority of bills on their way to a vote, though, it made DeLeo the person members from across the state had to convince to move their measures, large and small, to the floor—and put the young politician in the center of the action. “You have to be a goalie,” Finneran says of the post. “I think that’s where his personality and skill set became more apparent to the membership.”

Representatives soon got to know DeLeo as a friendly ear with a genuine interest in the issues that mattered to them, even if he ultimately did not agree with them, or their positions, says Michael Moran, a Brighton state representative and DeLeo’s second assistant majority leader. Still, Moran adds, in a position like that one, members “get to see what you’re about. Not only what you ultimately did, but did you listen, and did you give them an explanation?”

As DeLeo racked up points with his fellow members, another scandal plunged the House back into chaos. In 2004, Finneran stepped down because he was being investigated on charges of perjury and obstruction of justice; he would be indicted the following year. Once again, it left an opening for the speakership, which was quickly claimed by Finneran’s ally, Majority Leader Sal DiMasi. A big man and an even larger presence, DiMasi initially promised a new era, one with decentralized control and increased transparency. Instead, he swiftly cleaned house and elevated loyalists to powerful positions. In a surprise move, he named DeLeo—who was almost universally liked but was not seen as leadership material—chairman of the powerful Ways and Means Committee, which controls the purse strings of the House. (DeLeo was also apparently surprised; at the time, he had been looking for a judgeship.)

DeLeo took to the new position like a shark to water, suddenly the man in command of members looking to fund projects in their districts, and able to exert control over the budget and spending bills on behalf of DiMasi. Meanwhile, despite his early overtures to loosen the speaker’s grip on the House and increase transparency, DiMasi clamped down hard—and, as it turns out, brought new meaning to the phrase “Absolute power corrupts absolutely.” He ultimately resigned in January 2009 after the feds began investigating him for taking a kickback in exchange for awarding a state contract to a software company. He was later convicted and sentenced to eight years in prison.

DiMasi—for those keeping score at home—was the state’s third straight speaker who had been indicted, but if House members were ready for a fresh start, they didn’t show it. DeLeo was one of two DiMasi loyalists who, along with an outsider, jockeyed for the support of the rest of the members to become House leader. When the dust settled, the unassuming rep from Winthrop emerged with the speaker’s gavel in his hand.

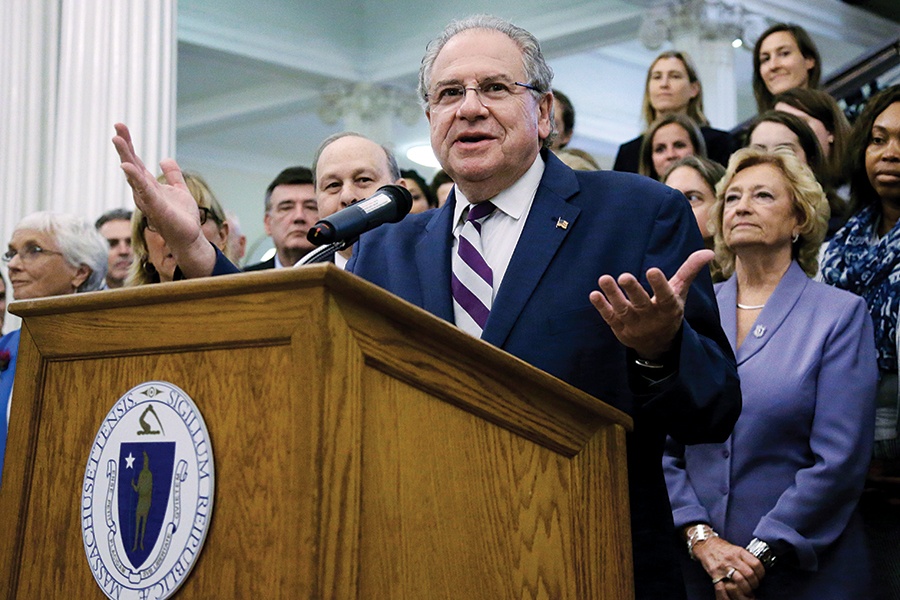

Widely considered an affable and likable consensus-seeker who has championed important legislation during his tenure, House Speaker Robert DeLeo has also drawn fire from critics who say he acts like an autocratic leader, favoring those who comply with his wishes and disfavoring those who don’t. / Photo by Charles Krupa/AP Images

At first, it seemed like DeLeo might not follow in his predecessor’s footsteps. In contrast to the men who came before him, he was self-effacing, affable, soft-spoken, and kind of schlumpy. There were early indications that he might govern differently, too. DeLeo quickly instituted a series of reforms aimed at restoring a scandal-weary public’s faith in the disgraced House and in the office of the speaker. Foremost among them was his move to reinstitute a four-session (eight-year) term limit for the speaker, which he said was the only way to ensure the continual emergence of fresh ideas. At the same time, though, he made sure that every member of the House knew he was now the boss.

Case in point: the 2010 racetrack debacle. DiMasi had been a staunch opponent of gambling, but when DeLeo—a veritable son of horseracing whose district included Suffolk Downs and the Wonderland greyhound track, which together were pursuing a casino license—took over, gambling proponents sensed they had a powerful ally. They were right. Eager to pass a bill that would have allowed slot machines at racetracks, DeLeo appeared willing to stop at nothing to succeed, threatening to hold up unrelated legislation for ransom until he received the support for the bill he wanted. When then-Governor Deval Patrick indicated he would not sign the bill, it should have been a stinging defeat for DeLeo. Instead, he turned it into a tour de force.

Staging a dramatic late-Saturday-night press conference, DeLeo stood in front of the grand staircase of the State House, making sure dozens of House members were standing behind him. Then he delivered a stinging rebuke to the governor, who was facing an uphill reelection bid. “Make no mistake about this,” DeLeo boomed through his microphone. “Anything short of Governor Patrick signing this bill represents a decision to kill the prospects of 15,000 new jobs and bring immediate local aid to our cities and towns.” Prior to that moment, it was unclear exactly how much staying power or control over other members DeLeo would have. That night, he delivered the answer with an exclamation mark. His bill may have failed, but he had sealed his reputation as a speaker to be reckoned with.

During the ensuing decade, DeLeo’s power has never been in doubt. He has not only been able to hold his own in the House, but he often gains the upper hand when negotiating with the other two legs of the state’s legislative triad: Senate Democrats and the governor. As a result, he has seldom, if ever, suffered another loss like the casino bill, and it is in no small part because of the degree to which he controls the House. From 2017 to 2019, for instance, Democrats cast a total of just 672 votes that ran contrary to DeLeo’s. To put that in perspective, that means, on average, each Democrat voted against DeLeo fewer than two times per year. In 2019, fully two-thirds of the House Democrats voted with DeLeo 100 percent of the time. No other speaker has been able to get members to move in such lockstep.

For some, DeLeo’s ability to garner support and achieve consensus—a word the speaker employs frequently—is the key to getting things done in a House of 160 members with disparate viewpoints. “The decisions that he has made have always been in the interest of moving the agenda forward for the entire membership,” says Aaron Michlewitz, the current chair of the House Ways and Means Committee. DeLeo’s supporters say he achieves consensus by being a good listener, by treating members with respect, and by working arduously toward compromise. He also does it by staying fiercely loyal to his members. “He takes the role of ‘I am the speaker, and I have to protect the members’ very seriously,” says one longtime State House observer, “and most of the members appreciate that.” That protection means not making members take tough votes that would hamper their ability to be reelected.

DeLeo’s supporters say the protection he offers, along with his likability, has won him the loyalty he’s needed to pass key pieces of legislation, including major ethics reforms for the House in 2009, a minimum-wage increase and gun-control laws in 2014, a transgender-rights law in 2016, and, in 2019, a law to reform school funding. In particular, supporters say, DeLeo’s drive to get the gun law passed showed the artistry of his ability to garner consensus. “In the democratic process, one has to come to compromises,” Representative Alice Peisch of Wellesley says. “Bob takes the time to listen to all the members’ concerns. At the end of the day, that becomes important when it comes time to implement.”

In January 2015, at the start of a new year and a brand-new two-year session, Speaker DeLeo convened a caucus meeting in the Bulfinch Room to vote on a few House rule changes. By all accounts it was shaping up to be a tedious nonevent—until, that is, members angrily told a few journalists who were also gathered in the room that they had to pack up and leave at once. Seconds later, security guards grabbed them by the arm and, cursing, ushered them out of the space.

Once the state’s political reporters were gone, the doors were closed and members voted on a rules package that would make any autocrat smile, abolishing the very term limits that DeLeo had reinstituted just six years earlier when he first took over as speaker. After the votes were tallied, only 11 Democratic members disagreed with the rule changes and voted against letting DeLeo become Speaker for Life. Later, when reporters asked DeLeo to explain his change of heart, he said that his thinking on the issue had simply “evolved.”

DeLeo’s evolution was just getting started. At the beginning of the 2017 legislative session, he made another power grab, asking members to vote on a rules package that included significant stipend increases for representatives who receive leadership and committee-chair and vice-chair appointments. In many cases, these stipends doubled. DeLeo has also increased the number of positions that receive this additional compensation. Today, fully 86 Democratic representatives get significant pay bumps compliments of DeLeo, who appoints members to chair, vice-chair, and other leadership positions. “When you pay 86 people, then you have 86 votes that are essentially in your hands for everything you need,” says Holmes, who argues that this gives DeLeo inordinate power over his reps. “So you can pretty much run the building because you have the 86, and then you have the 15, 20, or 30 other members who want to be in the next paid group.”

Perhaps tellingly, the 47 members who have received leadership or committee-chair positions from DeLeo have collectively voted against the speaker’s position just 31 times in the past three years, on more than 600 roll-call votes. “There isn’t really any vote whipping,” says another House insider, in reference to the traditional work of keeping party discipline in the legislature. There’s “just fear of retribution.”

That fear appears warranted, especially if you listen to people who have faced the consequences of speaking out against DeLeo. Jonathan Hecht of Watertown, for instance, was one of the 11 members to vote against removing term limits that day behind closed doors, and afterward delivered an impassioned speech supporting his position. Soon after, DeLeo stripped him of his long-held position as vice chair of the Elder Affairs Committee. A couple of years later, when Holmes publicly suggested that the House needed to find a new speaker, he soon found he was no longer the vice chair of the Housing Committee. And late last year, former Representative Jay Kaufman revealed that back in 2013, DeLeo threatened to rescind his committee chairmanship if he voted against a tax bill DeLeo supported.

Even if you took away DeLeo’s ability to make appointments, critics say, he has plenty of other ways to keep members in line. Holmes says that desirable offices and the number of aides allotted have reportedly been used to exact compliance. That’s not all. When Holmes, already stripped of his Housing Committee position, spoke in favor of abolishing the system of paying committee chairs and vice chairs—and instituting a system of pay parity like the one that exists in the U.S. Congress—he says leadership slashed the amounts of budgetary earmarks that had long gone to three community organizations in his district. And last fall, when three first-term Democrats, Maria Robinson of Framingham, Tami Gouveia of Acton, and Lindsay Sabadosa of Northampton, spoke out in the press claiming they were prevented from speaking on the House floor, the women instantly became “radioactive,” according to one government-relations veteran who works closely with Beacon Hill. “Lobbyists don’t want to work with them. Other members don’t want to work with them. They are persona non grata.”

DeLeo’s office denied many of these allegations and questioned Holmes’s interpretation of events. In a written statement DeLeo himself called Kaufman a liar. Meanwhile, Catherine Williams, his communications director, said the three first-term representatives have met with the speaker about various issues so far this year. She also said that while DeLeo selects members for leadership, chair, and vice-chair positions, the entire Democratic caucus votes on them.

DeLeo’s power is felt even outside the corridors of power on Beacon Hill. Eight political insiders, including lobbyists and former staffers, recently wrote an op-ed in CommonWealth magazine saying that if an organization upsets the speaker, House leadership will block bills important to the group or even call its funders to ask them to withhold their financial support.

How does DeLeo get away with it all? Much of this happens without his direct involvement—“He’s the ultimate good cop,” says one House insider. In the case of the three now-radioactive female representatives, it was reportedly Michlewitz, Representative Paul Donato, and Representative Denise Garlick who shut them down. According to Holmes, DeLeo recruits others in the House, such as Moran and Majority Leader Ronald Mariano, to act as his muscle and bully members into compliance. “You can see who he really is by looking at the people he deploys and empowers,” Holmes says. “When you have those people around, sure, you can be affable, you can be kind, and you can seem as though you are listening.”

Photo by Elise Amendola/AP Images

Over the long stretch of time that DeLeo has served in the House, no one has been able to prove that he is corrupt like his predecessors. But the feds sure have tried.

In 2010, the Globe ran a report that found a rigged hiring and promotion system at the Probation Department that was heavily influenced by recommendations from state lawmakers. The story repeatedly emphasized DeLeo’s role as one of the lawmakers whose recommendations were linked to preferential treatment, and U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz called him an “unindicted conspirator,” alleging that he was involved in a scheme to use patronage influence as currency with fellow lawmakers. In the end, DeLeo was never charged with a crime, and ultimately the U.S. Appeals Court dismissed the allegations, but the scandal did reveal his antiquated attitudes toward patronage. While he denied any knowledge of wrongdoing, he told investigators that he didn’t see the matter as an ethical issue, but rather a case of legislators trying to help qualified constituents.

This isn’t the only instance in which DeLeo’s management of the House has appeared woefully out of step with public expectations for the times. At the height of the #MeToo movement in 2017, for example, a Globe column cited a dozen women alleging a climate of harassment and sexual misconduct in the State House and described an environment in which women felt they had no other option than to remain silent. Instead of hiring an outside investigator to review the allegations and the House’s response to them, as many organizations have done, DeLeo assigned the task to House Counsel James Kennedy, formerly a DeLeo staffer. That was a poor choice, says state Senator Diana DiZoglio, who has been critical of the fact that Kennedy was asked to investigate what went wrong in a process he was responsible for. “It’s unacceptable,” she says.

DeLeo’s office defended Kennedy’s review, which resulted in new recommendations that were unanimously adopted by the House, saying he “laid bare the existing structural, procedural, and policy deficiencies of the House’s human resources function.” But one thing the report did not explore (and an independent investigation might have) is how Kennedy himself and the concentration of power around DeLeo created an environment in which people were scared to report incidents of any kind of harassment, sexual or otherwise.

At the same time, the speaker also resisted calls to end the practice of forcing victims to sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) when settling complaints against House members—which DiZoglio says is “using taxpayers’ dollars to keep people quiet and benefit the member personally and politically.” There have been 33 NDAs signed during DeLeo’s tenure as speaker, none of which, DeLeo claims, was related to sexual harassment. Since the new recommendations came out—which include restrictions related to the use of NDAs—DeLeo’s office says it has not signed any NDAs, and Williams says new rules require three independent officers of the House to approve any settlement claim.

Meanwhile, in an era when the public demands ever greater transparency from its elected officials, DeLeo has proven to be an elusive and press-averse speaker. Just this January, when he entered Symphony Hall for Mayor Marty Walsh’s state of the city address, according to a bystander, his chief of staff, Seth Gitell, put his body between the speaker and reporters to block him from their questions.

Taken together, these incidents tell the story of a man who has stayed on the right side of the law but who has also fallen behind the times. Back in 2009, DeLeo said he believed that keeping the same speaker in office for too long hampered the emergence of new ideas. Since then, it seems to some, he has proven that point.

As DeLeo continues to make moves that arguably keep the House in the past, the future is already happening outside Beacon Hill. A totally new breed of politician is running for office in Boston and beyond—and winning. These are not neighborhood guys simply trying to look out for their districts, as DeLeo was; they are activists, seeking to drive broad ideological agendas in an equity framework. Outsiders, in other words, are the new in-crowd, and the old guard may not be able to hold them back much longer before they breach the walls of the House, too.

In fact, chinks in DeLeo’s armor are already starting to appear. In 2018, Boston voters ousted two high-ranking members of DeLeo’s leadership team: Ways and Means Chairman Jeffrey Sanchez and Assistant Majority Leader Byron Rushing. It would be tough to say that these were votes against DeLeo, as both races were more complicated than that. But it is true that at the very least, DeLeo was unable to save either man. More primary challenges to DeLeo loyalists are in the works for 2020, in Boston and elsewhere.

Some see signs of internal turmoil as well. One Beacon Hill insider says that the House is no longer so efficient, which is one of the supposed advantages of a top-down leadership style. Massachusetts, for instance, has been the last state in the nation to pass its budget for the past two years. At the same time, another State House insider says, the House has been functioning less smoothly since DeLeo’s two top staffers, Eisenberg and Toby Morelli, left two years ago for the private sector. “[DeLeo] is not holding it together as well,” this person says. “It’s increasingly disorganized chaos.”

That disorganization has only gotten worse as speculation over who will be DeLeo’s successor reaches a fever pitch. DeLeo stated in October, and reiterated in January, that he will be seeking reelection to his representative seat once again in 2020, but insiders believe he may simply be seeking to avoid the appearance of a lame duck and will surprise members by not running again. In fact, by the time you read this, he may have already announced he will not run for reelection this year. That would mean the speakership would be open in early 2021.

Would-be successors have quietly been angling for support in case DeLeo does leave. The two most active have been Speaker Pro Tempore Patricia Haddad of Somerset and Majority Leader Ronald Mariano of Quincy. While it is true that these are some of the very people who helped DeLeo erect the foundations of his governing style, it seems unlikely that they will be able to rule with the degree of control DeLeo commands. “Even if the new speaker is a hand-picked successor, he or she may not be able to lay down the law quite so effectively,” says Matt Miller, cofounder of the advocacy group Act on Mass. After all, “There are a number of new reps who don’t have this history of how things have been done.” Already the group has gotten 12 Democratic representatives to sign a pledge for greater transparency in the House, and there has recently been a flurry of candidates interested in signing on as well, meaning we may hear a lot more about reforming the House as the campaign season gets under way.

Meanwhile, Representative Hecht has been unsuccessfully arguing for secret balloting to elect the speaker to protect members from potential retribution. Still, all of this is largely theoretical at this point, as no one knows when DeLeo will step down, or why he would be motivated to do so. After all, what would he do next? He doesn’t like to travel. He doesn’t have his eyes on the national stage. He doesn’t even appear to like mingling socially in power circles in Boston.

When he does step down, he will most likely return to the quiet confines of Winthrop, where he sits at his regular table at the Winthrop Arms and orders the fried clams. It is an insular community where neighbors still look out for one another, and where the outside world and many of its changes have so far been kept at bay. In fact, it is a lot like the House DeLeo has built on Beacon Hill.