How the Famous Hood Milk Bottle Arrived in Fort Point

The inside scoop on Boston’s most incongruous architectural icon.

Today the Hood Milk Bottle remains a fixture of Fort Point. / Photo by Openroads.com/Flickr

Any list of the city’s most iconic landmarks would have to include the Hood Milk Bottle. A beacon for the Boston Children’s Museum, which stands a few yards away, the 40-foot-tall bottle is instantly recognizable to tourists and locals, tots and grownups. But the bottle’s backstory isn’t quite as well known—and it’s as strange as the structure itself.

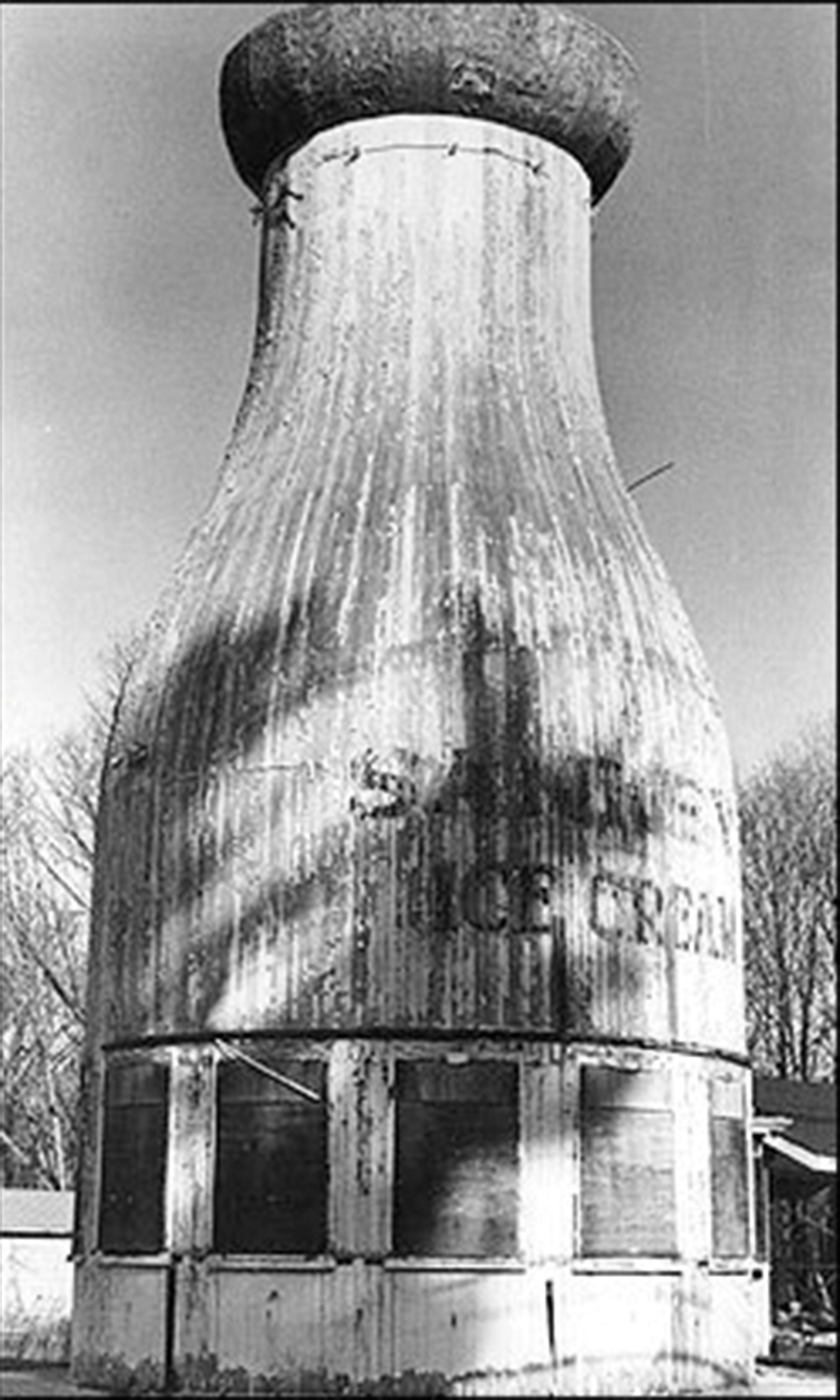

The bottle got its start in 1933 as a roadside stand for ice cream maker Arthur Gagner, who used it to beckon drivers on Route 44 in Taunton. The massive bottle—roomy enough to hold 58,620 gallons if it were real—was certainly a novelty, though Gagner wasn’t the only entrepreneur to employ fanciful architecture to catch the eyes of customers. As car ownership became commonplace, giant doughnuts, coffee pots, hot dogs, and other surreal shapes rose up on roadsides across the country, enticing motorists to pull over. Gagner peddled sweet treats from his whimsical wooden stand for a decade before selling the building to the Sankey family, who also used it to sell ice cream. But by 1967, the bottle had been abandoned. In 1974, photographer Walker Evans took a Polaroid of the forlorn building—a snapshot that now belongs to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

After Sankey’s Ice Cream shuttered, the bottle languished for several years in its original location in Taunton. / Photo courtesy of Boston Children’s Museum

After languishing for eight years, the bottle found an unlikely savior: Carol Scofield, a clothing designer and, as it turns out, a fan of roadside Pop architecture. She saw the building while driving by and bought it for $2,500. Then she called John Sloan, director of urban design for the Boston Redevelopment Authority (now known as the Boston Planning & Development Agency), and asked if he had any ideas for repurposing it. Sloan thought the bottle would make a perfect addition to City Hall Plaza; he imagined it selling ice cream in the summer and hot chocolate in the winter, bringing life to the vast brick expanse. One of his colleagues had a friend who worked at Hood, which agreed to fund the bottle’s restoration. But the mayor’s office quashed the plan: Gerhard Kallmann, one of the architects who led the design of City Hall in the 1960s, had made it clear he viewed the idea as an affront to the building’s dignity.

Sloan went back to the drawing board, seeking another underused urban space that needed a little levity. Eventually he reached out to the Children’s Museum, which was preparing to move from Jamaica Plain to a former wool warehouse on Congress Street Wharf. The playful take on a kid-friendly beverage was a hit with the museum’s board. Before long, the bottle was off for refurbishment in Quincy, where workers sanded off 14 coats of old paint. On April 20, 1977, it bobbed across Boston Harbor on a barge escorted by two fireboats, and a crowd cheered as a crane delivered the 15,000-pound bottle to the doorstep of the soon-to-debut museum.

The refurbished bottle made a grand entrance in 1977, floating across Boston harbor before being installed in its new home. / Photo courtesy of Boston Children’s Museum

Over the years, the bottle has hosted various vendors, from Hood to Au Bon Pain to Sullivan’s. It quickly turned into a fixture of Fort Point. “The bottle became such a good symbol for the museum back in the 1980s that many signs around the city were just a graphic of the milk bottle and an arrow—it was so well known,” says architect Peter Kuttner, principal of CambridgeSeven, the firm that helmed a renovation of the museum in 2007. By that time, the bottle was looking battered, having suffered water damage during storms. CambridgeSeven cut the structure in two, rebuilt the bottom half, reinforced the top, and moved the bottle slightly to a higher-elevation spot. “We were pleased to be able to save as much of it as we possibly could,” Kuttner says.

Today, with seas rising due to climate change, the waterfront plaza the bottle calls home is again in the spotlight. The Children’s Museum recently tapped local design firm Sasaki to devise a resilience plan to address flood risk and reimagine its stretch of the Harborwalk as an even better place to play. Here’s hoping it helps a quirky icon stand tall for generations to come.