A Dream Deferred

For a moment, Boston had a chance to elect its first Black mayor. What does it say about our city that we didn’t take it?

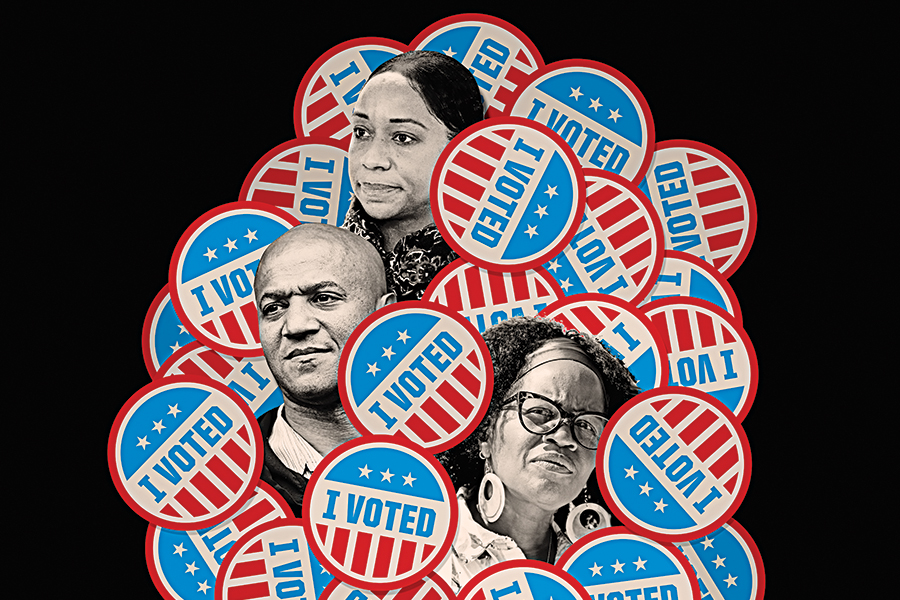

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis / Photo by Matthew J. Lee/Boston Globe/Getty Images (Campbell); Pat Greenhouse/Boston Globe/Getty Images (Barros, Janey)

On primary day in Boston, I thought I’d outsmart the crowds. I waited until early afternoon before walking the few short blocks to my Ward 4 polling station at Tent City near the South End to cast my vote for mayor.

I had good reason to expect a crowd. The first time a Black candidate made it to a general election was in 1983, when Mel King lost to Ray Flynn, and even though nearly 40 years had gone by, the city still hadn’t elected a Black mayor. This time, it felt like residents had a real chance to finally get over this hurdle that has helped cast a dark shadow over the city’s national reputation. Not surprisingly, the election was getting ink everywhere from the New York Times to the Los Angeles Times. Meanwhile, I’d spent weeks fishing reams of candidate fliers out of my mailbox and had seen legions of campaign volunteers going door to door in my Roxbury neighborhood.

Surely, everyone in Boston knew how big this moment was, right? And surely, I thought, the line to vote early that morning would stretch down the street. I wasn’t about to get stuck in it. Yet when I arrived at the polling station, instead of being relieved that there were no long lines, I was immediately concerned to see that there was no line at all. When I entered the voting room, it was just me, a few poll workers, and one other voter. A volunteer there told me I was only the 41st voter that day.

I cast my ballot for City Councilor Andrea Campbell and headed back home. That night and the next morning, I found myself glued to Twitter watching the results being reported in real time. At one point, after mail-in ballots were counted, Campbell’s numbers suddenly shot up and I thought she had a chance to finish in second place and move on to the general election. But my hopes were soon dashed. After all of the votes from Boston’s 22 wards were finally counted, Michelle Wu had won 33.4 percent of the vote, Annissa Essaibi George had come in second with 22.5 percent, and neither interim Mayor Kim Janey nor Campbell had made it to the final.

The outcome stung, but all the more so because of the hope that had been built up over recent years by the successful political campaigns of Ayanna Pressley for Congress, Rachael Rollins for Suffolk County district attorney, and Nika Elugardo for state representative. It all seemed to suggest that the city had turned a corner and might finally elect a Black mayor.

Boston, though, rarely balks at an opportunity to remind us that not all of its residents are so quick to change. That we haven’t made as much progress as we think we have. Was it possible, I wondered, that Boston is still—after all these years—simply unwilling to have a Black person lead the city?

After the primary election, many pundits seemed to have a take on how Boston had lost a historic chance to elect a Black mayor, and I was determined to figure out who was right about what went wrong.

In the days after the primary election, many local political pundits and Twitter users seemed to have a take on how Boston had lost a historic chance to elect a Black mayor, and I was determined to figure out who was right about what went wrong. It proved impossible because, in a way, they were all right. What led to no Black candidate advancing to the general election was a perfect storm of circumstances.

One of the most popular theories was something that many had identified long before election day: With Janey and Campbell, two Black candidates, both polling well during the campaign, they would split the vote of the city’s Black and Latinx communities, resulting in neither of them winning. That seems to be precisely what happened. Campbell drew 19.7 percent of the vote and Janey received 19.5 percent. Together they would have accounted for 39.2 percent of the total vote, which was more than the first-place Wu garnered.

The problem was that no one seemed to agree on which of these candidates should have run. Campbell’s supporters argued that she was a strong candidate who declared early and even won the endorsement of the Boston Globe. Janey supporters pointed out that she was already in the mayor’s office and should have been the chosen one because she could leverage her incumbency. But that’s where another tough circumstance came into play—Janey had been in office for only six months, which was hardly enough time to prove herself as mayor, and yet the responsibilities of running the city left her little time to prove herself on the campaign trail.

In response to the blame being heaped on Janey and Campbell, State Representative Liz Miranda lamented in a tweet that “Black women get blamed for so much in Boston.” She has a very good point. What virtually no one was saying in the aftermath of the election—but can’t be denied—is that John Barros, a man, and the third Black candidate, had virtually no chance of being elected mayor and yet he stuck it out. Had he dropped out of the race and lent his support to either Janey or Campbell, the 3,436 votes he received would have been enough to allow either of them to beat Essaibi George for second place, and I wouldn’t be writing any of this right now.

After the primary, I thought often of the seventh episode of the 2020 Netflix documentary series Trial 4. In it, Reverend Eugene Rivers III spoke about Black ballot power in Boston. “Blacks don’t have, in this city, the organizational infrastructure to engage in power aggregation,” he said, adding that, “The reason that Black people have not elected a Black mayor in all this time…is that Boston…consists of a bunch of Afro-Caribbean Blacks, so they would not close ranks to elect anybody Black because they’d be fighting over which island the person was [from]…. In that context, all you’re going to do is be defeated.”

That might not have been the exact case in this election—Janey’s father’s family has roots in Guyana but Campbell’s father was born in Boston in 1933 and both have close ties to Black Boston’s Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan neighborhoods—but the argument is valid. There was a sharp division in the Black community between Janey’s and Campbell’s supporters, with both camps accusing the other of mudslinging and then assigning blame to the other for the fact that their candidate didn’t win.

All of this, however, begs the question of why people see having multiple viable Black mayoral candidates as a weakness rather than a strength. After all, as many asked in the aftermath of the primaries, why shouldn’t Boston be able to have three black candidates running for office and still have one of them elected, just like it has always played out for white candidates?

In a perfect world, as many Black people who want to run for office should be able to, but maybe until residents break the racial barrier for the first time and elect a Black mayor, it makes sense to tear a page out of the Irish Boston political playbook. Back in the 1880s, Irish-American community leaders selected one man, Hugh O’Brien, and worked hard to make sure every Irish person voted for him. It worked, and the Irish went on to successfully select an Irish mayor for the next hundred or so years.

At the same time, other pundits pointed out that maybe it wasn’t a case of having too many Black candidates, but not enough Black voters. Low voter turnout benefitted Essaibi George, who won predominantly white districts where turnout was higher than it was in any of the districts that any of the other candidates won. Had more Black voters simply cast their vote for either Campbell or Janey, either of them could have advanced to the general election.

Former longtime Massachusetts state Representative Byron Rushing wasn’t surprised by the outcome and says it speaks to the sad state of Black politics and Black political power in Boston. “The fact that they [Janey, Campbell, and Barros] believed Boston changed enough in the past eight years since Black candidates lost to Marty Walsh speaks to the incredible disorganization of Black people in the city around politics,” he said, adding, “Black people in Boston are not interested in electoral politics.” Could it be that after more than 50 years of countless political failures and disappointments, Black Bostonians don’t have enough faith in the system to care anymore about being part of it?

And what about white liberals? Aren’t they partially responsible for not flexing their bona fides and coming out in force to support and vote for Black candidates? Another circumstance was clearly at play: In Michelle Wu, white liberals already had a progressive, female candidate of color with widespread name recognition, one who had practically been campaigning—or at least heavily hinting at a run—for the past three years. If anyone blames them, though, they also have to blame the Black Bostonians who voted for Wu: I know some Black voters were so daunted by the messy divide between the Janey and Campbell camps that they chose to vote for neither of them. Maybe no one of these circumstances would have resulted in the outcome we saw, but put them together and it was all but inevitable.

More than 42 percent of those who voted chose a Black candidate. Amid the disappointment, that in and of itself is cause for optimism.

After the preliminary primary results came in, Renée Graham of the Globe tweeted, “With three Black candidates in a five-person race, the question was often asked: ‘Is Boston ready to elect a Black mayor?’ On Tuesday, Boston answered as only Boston would. No.” When I asked her about the tweet, she told me, “In the city’s history, only twice have Black candidates even gotten to the November election. Boston remains one of the only major cities never to elect a Black mayor.”

While that’s true, on September 14, 2021, more than 42 percent of those who came out to vote chose a Black candidate. That’s more than any other single candidate. Amid the disappointment, that in and of itself is cause for optimism.

I suppose that’s still little consolation for many Black Bostonians who feel as though they have no idea when they’ll have another opportunity to seal the deal. And they have a point. Over the past 60 years, there have only been six mayors. While the mayor of Boston serves a four-year term before facing reelection, there are no term limits, so the job is pretty much yours for as long as you want it. You can likely keep the position until you die or score a job in Washington, DC. In other words, the job may well belong to Michelle Wu for as long as she wants it.

Still, I don’t agree that we might not get another chance. I equate it to when the Boston Red Sox lost an epic battle to the New York Yankees in seven games in the 2003 ALCS, only to return to the ALCS in 2004 versus those same Yankees. They found themselves down three games to none before pulling off the greatest comeback in modern sports history, and then they broke an 86-year curse to finally win the World Series. The first time Hugh O’Brien ran for mayor he lost, only to become the first Irish-American mayor the next time around. History tends to repeat itself, especially in this city.

When I think about all the young, enthusiastic Black and Latinx candidates running for city council and the many potential future mayoral and gubernatorial candidates currently filling public offices in Boston and across the state, my mind won’t allow me to think negatively about Boston’s political future even in the face of this recent letdown. I believe that the 2021 preliminary mayoral election will serve as a call to arms for future generations of politicians and voters alike, and that these communities won’t let another opportunity to make history slip through their hands. The fight for progress in Greater Boston takes longer than we’d like, but the struggle is worth it.