Garrett Harker Conquers Kenmore (Again)

Can lightning strike twice? After his iconic brasserie, Eastern Standard, shuttered during the pandemic, Boston's consummate hospitality wiz is reopening the restaurant this month—and putting everything on the line that it will.

For the new incarnation of Eastern Standard, Garrett Harker is bringing back the iconic red banquettes. / Photo by Pat Piasecki

At first impression, this silver-haired sage of the service industry—the man who launched some of the city’s best-known dining establishments, including Kenmore Square’s late and great Eastern Standard Kitchen & Drinks, and mentored so many talented tastemakers (James Beard Award–winning chef Jamie Bissonnette, nationally lauded mixologist Jackson Cannon) who have put their own lasting mark on the city—seems friendly yet a bit inscrutable. Though Harker certainly has much to say about Boston’s restaurant industry (especially as it exists post-COVID), I quickly get the sense that talking about himself is not his favorite thing to do. “Where were you married?” I ask at one point during our conversation when he mentions tying the knot with his ex-wife. He answers, but not without first asking to know why.

If Harker is a fairly private guy, at least compared to many glad-handing restaurateurs, perhaps it’s because he had early practice at ceding the lion’s share of the public spotlight: When he swept into Boston in the late ’90s, a cool breeze from San Francisco’s far chicer restaurant scene, he landed at soon-to-be-famous chef Barbara Lynch’s first baby, No. 9 Park. Lynch, of course, wound up a massive brand name for her near-peerless talent and swaggering, salty confidence in and out of the kitchen. As No. 9’s opening general manager, though, it was Harker who, sans pomp, brought the operational savvy and elegant front-of-house choreography that quickly defined the landmark dining room, which for years was widely recognized as Boston’s finest.

Where Harker set himself apart was with the 2005 opening of Eastern Standard in Kenmore Square, then a gray and gritty intersection populated with greasy spoons, grimy punk clubs, and interloping Red Sox fans. A hit out of the gate, his debut solo venture was a perfectly triangulated crowd-pleaser. From the steak frites to the craft cocktails to the late-night specials scrawled on a mirror behind the long, long bar that never stopped buzzing, it was an American brasserie that somehow brought everyone together: the special-occasion diner, the pregame hordes, the industry shift worker pounding a signature whiskey smash before the T ride home. Its secret? Harker had dialed down the Brahmin refinement of Lynch-land just enough to democratize it.

In its heyday, the original Eastern Standard was a spot that brought everyone in Boston together. / Photo courtesy of Eastern Standard

He soon followed up Eastern Standard with two neighboring ventures: ocean-to-table bellwether Island Creek Oyster Bar—a partnership with celebrated chef Jeremy Sewall and a pair of Duxbury oyster-farm entrepreneurs, Shore Gregory and Skip Bennett—and cocktail den the Hawthorne, which became a nationally laureled entry in the craft-cocktail renaissance of the 2010s thanks to the talents of beverage director Jackson Cannon. Although he would eventually expand into ventures beyond the neighborhood—including the more-casual Row 34 restaurants in Fort Point and the ’burbs; Branch Line, a rotisserie-focused Watertown restaurant; and the now-defunct French spot Les Sablons in Harvard Square—Harker was perhaps best known for his radical transformation of Kenmore Square. “I would say he single-handedly created the soul of Kenmore,” says real estate mogul John Rosenthal, the mastermind behind the upcoming $1.3 billion Fenway Center, a massive mixed-use development that includes the Bower.

Indeed, for more than a decade, Boston’s dining world revolved around what the restaurateur’s peers affectionately called “Harkertown.” Then it all came crashing down. In 2021, Eastern Standard, Island Creek Oyster Bar, and the Hawthorne—which at one point were netting $19.5 million annually, according to the Boston Globe—abruptly closed over a landlord-related “misalignment.” That’s the diplomatic word Harker now uses to describe a row over the rent that got so big and so public it hit the New York Times. Supporters rushed to Harker’s defense. His former landlord, meanwhile, rushed to fill the vacant spaces at the Hotel Commonwealth with a new tenant, a New York City–based hospitality group that opened—wait for it!—an American brasserie, a seafood restaurant, and a sushi bar there. Sound (mostly) familiar?

Now that Harker’s two-year non-compete with his former landlord is over, Harker is looking to reassert his dominance just a few blocks away at the Bower, where he’s reopening the beloved Eastern Standard as well as his own new seafood restaurant, All That Fish + Oyster, a cocktail bar called Equal Measure, and a café. He’s essentially reviving his old successes within spitting distance of the restaurants that took their place. If you think that sounds a little pointed, you’re not alone. “I think he’s pissed,” says David Hadden, a former investment banker and restaurant adviser who helped launch No. 9 Park. “I think part of it is that he wants to come back and say, ‘Screw you.’ And he can do it. He can deliver.”

Harker himself is too gentlemanly to be petty, but read between the lines and you see a man who, despite his success, perhaps feels he has something to prove right now. “People used to say Eastern Standard had the longest bar in Boston. I have no way of knowing if that’s true,” Harker tells me. “All I know is that I wanted this [new] bar to be a little longer than the old one.”

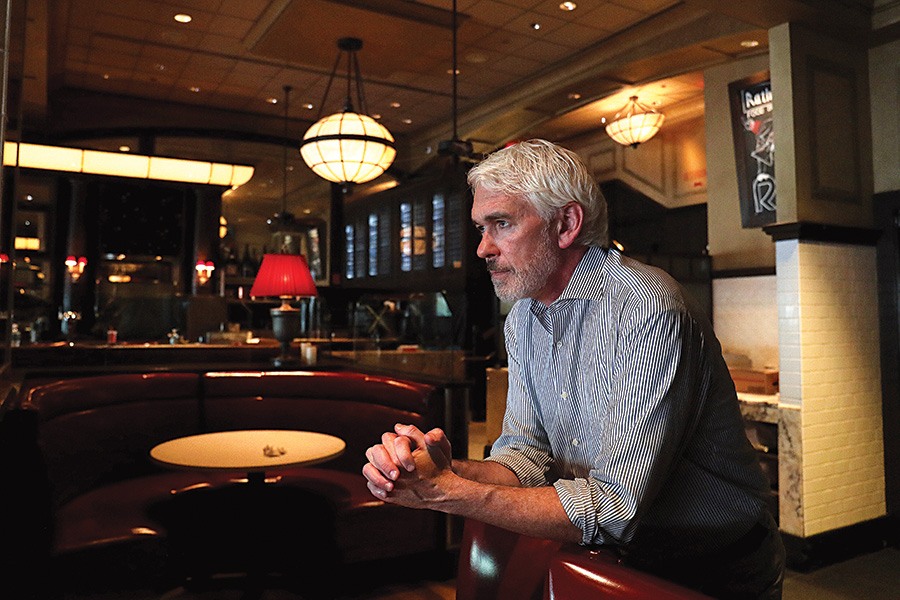

Harker inside the new Eastern Standard in Kenmore Square. / Photo by Pat Piasecki

Eventually, it would become one of the most consistently crowded dining rooms in Boston. But the first time Garrett Harker set foot inside 528 Commonwealth Avenue, the place was packed with racks of Red Sox jerseys.

While it awaited its first tenant, the soon-to-be restaurant space at the newly opened Hotel Commonwealth was serving as a wardrobe warehouse for a baseball movie, Fever Pitch, that was filming right around the corner at Fenway Park. The mood in the Kenmore-Fenway neighborhood was electric: Not only had the Drew Barrymore and Jimmy Fallon flick descended on the town, ushering in the excitement of Boston’s aughts-and-tens Hollywood East era (see also: The Departed, et al.), but it was about to immortalize on celluloid the Red Sox’s seismic 2004 World Series win, which marked the end of an 86-year championship drought.

All in all, things were looking up in the Hub.

With those winds of optimism in his sails—and in a particularly sunny economy, to boot—Harker was feeling hopeful about his own future. He’d decided to divorce himself from a souring years-long business partnership with Barbara Lynch to go it solo as a restaurateur, and his plans caught the ear of No. 9 Park regular Frank Keefe, a Dukakis administration vet. Keefe was part of a small constellation of real estate developers working, in tandem with leaders at nearby Boston University, to reverse the curse of commercial development in rundown Kenmore Square. One day, Keefe insisted Harker hop in his green Jaguar to go see the shell of what they hoped would become a popular restaurant.

The bigwigs already knew Harker was the man to make it happen. “Something we thought was important is that he wasn’t egotistical,” says Joseph Mercurio, former executive VP at BU, who helped lead the college’s transformation of Kenmore Square. “He was a down-to-earth, pragmatic, creative yet business-like person. He wasn’t a celebrity chef.”

The bigger question was whether Harker would take the opportunity. Friends and industry peers warned him against opening a restaurant in “Kenmore Scare,” as Eastern Standard’s opening chef (and punk-club regular) Jamie Bissonnette called the neighborhood at the time. Harker, though, smelled potential. By then, after all, he’d already hit it big launching two more restaurants with Lynch, B & G Oysters and the Butcher Shop, in the South End, a neighborhood where a wave of white-hot new restaurants was powering radical urban revitalization. “I’m really attracted to the idea of a challenge,” Harker says now, “where nothing is going to be handed to you.”

“I’m really attracted to the idea of a challenge,” Harker says, “where nothing is going to be handed to you.”

That tough work ethic was ingrained in him growing up in a lower-middle-class household in a largely Irish Baltimore neighborhood where, Harker says, community life mainly revolved around the local Catholic church. At his home, life revolved around homework: Harker’s mother, a no-nonsense schoolteacher who aspired to a higher family standing, ran a tight ship and kept her eldest child’s nose deep in the books. It paid off. Harker earned a full scholarship to a competitive Jesuit prep school an hour’s commute away, where he was the kid in the hand-me-down clothes. His mother’s academic rigor stuck with him through the years, too: At Eastern Standard, he introduced a hallmark curriculum—Standard Education—designed to keep staff fluent in the finer points of food and drink, as well as art, culture, current events, and other topics essential to informed tableside conversation.

Harker traces his passion for dining, meanwhile, back to his dad, an aluminum-siding salesman and “closet gourmet” who’d occasionally stop to buy oysters from roadside sellers on the way home from work. Father and son would shuck them together over a big basin sink in the basement, an experience that shaped the future Island Creek Oyster Bar operator’s belief that dining should blur the lines between the petite and grande bourgeoisie.

After graduating from Pomona College in southern California, Harker “chased a girl” to Boston and got a job as a server at Legal Sea Foods in Park Plaza, where he absorbed the service-first philosophy of big-fish restaurateur Roger Berkowitz. At Legal he also met his future ex-wife and followed that girl back to San Francisco, where he briefly worked as a paralegal while assembling law school applications, because it was the kind of responsible profession he’d been reared to pursue. Harker’s heart, though, had been hooked by the restaurant biz. He got a job working in a low-level management position with San Fran’s Kimpton Hotels & Restaurants group, committed to working his way up the ranks.

It didn’t take long for Harker to get noticed. He wound up the youngest general manager in the group’s history during his time at Puccini & Pinetti, a restaurant he took from the brink of death to one of the most profitable in the group. He did it while keeping his emotions in check in an industry where tempers often flare, says Pete Sittnick, former director of regional operations for Kimpton. That made him stand out. “I appreciated the way he related to people,” Sittnick says. “When you’re cool, calm, and collected, when you do show emotion, it becomes motivating. When little spikes of emotion came up with Garrett, you knew he meant it.”

By this point, though, Harker had two daughters and a wife who wanted to move back to her native Boston. So he reached out to the Hub’s top toques, including celeb chef Todd English, who offered him a job managing his hit restaurant, Olives, and spearheading his expansion. An industry friend, though, suggested Harker connect with one of English’s promising former protégées, a brassy, buzzed-about chef who needed a general manager for her debut restaurant on Beacon Hill.

Harker shows off the shiny kitchen inside one of his latest restaurants. / Photo by Pat Piasecki

That’s how Harker met Barbara Lynch over coffee. He was jazzed by her attitude, which was even stronger than the java. “She said, ‘I want the best restaurant in Boston,’” Harker recalls. “‘Do you know anything about how to do that?’”

The answer, evidently, was a resounding yes. After turning down English, Harker helped put No. 9 Park on the national map, followed a few years later by the Butcher Shop and B & G, ventures in which Lynch made Harker an equal business partner.

From the start, it was a complicated dynamic between she (instinctive, impassioned) and he (pragmatic, even keeled), simultaneously rewarding and challenging. As the years went on, Harker believes Lynch’s ego became increasingly inflated by the hype around her—although, he says, he wasn’t around to witness the bombastic chef’s reportedly toxic behavior toward her staff, alleged to include verbal abuse and sexual groping in recent New York Times and Boston Globe exposés. (Lynch has denied the allegations.)

For his part, Harker doesn’t want to say much about Lynch today. He credits her talent and sense of fair play while acknowledging that, over time, things deteriorated. “Barbara was one of the most humble people in the beginning,” Harker says. But then, “She started to buy into all the things that were being written about her.”

They butted heads for the last time in 2004, when Lynch shot down (“in colorful language,” he says) Harker’s ambitious proposal to roll out more B & G locations in the Boston area and, perhaps, beyond. It was now apparent to “G,” as he’d become known in the biz, that he needed to break away from the ampersand and prove he could stand on his own. His partnership with Lynch, who did not respond to questions, ultimately ended and she bought him out of their joint business.

That was hardly the end of Harker’s career in Boston—far from it. Just a year later, the restaurateur would open the doors to Eastern Standard. At the height of its powers, the restaurant simply hummed. Every night had the vibe of a party—one that never got out of hand, and one to which everyone was invited. It was a place, Harker recalls, where Governor Deval Patrick entered to a standing ovation for a celebratory dinner after winning his first election, and where John Henry and Theo Epstein broke bread over business meetings. But it was also a place unintimidating enough for anyone to wander into for a drink or a bite and receive the same level of service as the VIPs.

Eastern Standard was more than just a great place to hang out, though: Just as real estate developer Frank Keefe and the BU bigwigs had hoped, it was also pivotal to the evolution of the neighborhood, which went from dank to swank seemingly overnight. “Nobody could survive in Kenmore Square,” says Brookline-based restaurant mogul and Harker mentor Ron Shaich, founder of brands such as Panera Bread and Au Bon Pain. “Garrett transformed it.”

Pandemic-era closures coupled with a difficult landlord relationship forced Harker to close his trio of Kenmore Square spots. / Boston Globe via Getty Images

Harker has never been a mentor on Top Chef, sat on a Chopped judges’ panel, or otherwise ridden the food-TV gravy train like other star restaurateurs. But for a certain subset of Bostonians at least—the ones who sat in Eastern Standard’s iconic red banquettes every weekend—his face is famous enough to stop foot traffic.

“Garrett!” An excited voice clamors for Harker’s attention as we walk up to the patio outside one of his favorite restaurants, Taberna de Haro, a tapas-and-Spanish-sherry specialist in Brookline, just a short stroll away from the Bower and the hubbub of Fenway-Kenmore. The fan is a stylish middle-aged woman who lives nearby, a former Eastern Standard regular. Later, Harker will admit to me, a touch embarrassed, that he recalls her face but not her name. But right now, he’s just listening politely—flattered if mildly self-conscious—as she sings the praises of his past glory. “We had so many special memories there,” she tells him, her tone sticky with sentiment. “It was such a winning formula. They were foolish to play with you the way they did.”

The “they” she’s talking about is UrbanMeritage, a Boston real estate investment firm that in 2014 purchased the Kenmore Square properties that housed three of Harker’s restaurants. The relationship wasn’t a cozy coupling from the outset. Harker almost immediately found himself mired in years-long lease renegotiations with a company that, unlike Boston University and his other prior landlords, he says, didn’t seem invested in seeing his businesses thrive.

Then COVID-19 came crashing down on the industry, exacerbating Harker’s existing problems and creating new ones. While the restaurateur’s other landlords worked with him to help keep his ventures afloat during mandated closures, UrbanMeritage, he says, made no such effort. In May 2020, amid the ongoing negotiations, Harker says that he received letters from his landlord’s lawyer stating he had defaulted on his leases. Eastern Standard, Island Creek Oyster Bar, and the Hawthorne would have to close. “I was in denial for the longest time,” Harker says. “I thought it had to be some kind of performance on their end. I was probably the last person standing who thought in the eleventh hour it would get figured out.”

Harker, pictured in June 2020. / Photo by Barry Chin/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

While Harker is careful with his words, Jackson Cannon pulls no punches when offering his take on the situation. “They had zero interest in cooperating on us getting another 10 to 15 years there. Even before the pandemic, that was clear,” Cannon says. “They were cheap, they were rude, and I don’t care who knows it.”

The crushing experience with a seemingly intransigent landlord led to an outpouring of support on social media from Eastern Standard fans the world over. There were mournful paeans: “No! Please don’t be so,” tweeted Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a BU alum, alongside a heartbreak emoji. Others lambasted UrbanMeritage. (Cofounder and principal Michael Jammen, for his part, declined to comment for this story other than to say that earlier media reports “misrepresented” the situation with Harker. He declined to offer specifics.)

No! Please don’t be so – Eastern Standard was such an incredible place and home to so many wonderful memories.

— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@AOC) February 23, 2021

While Harker appreciated the flood of support, it did little to change the reality: The restaurateur was leaving the neighborhood he’d been instrumental in transforming, and he was a captain of industry with sunken flagships. Eastern Standard, his greatest success, didn’t even get a champagne-popping sendoff—just a shattered-sounding eulogy Harker posted on Facebook on the eve of its 15th anniversary. “So much happened between the beginning and now,” he wrote. “Thousands of extraordinary young people. Spectacular moments of hospitality. Countless times we fell short and had to come back the next day and try harder. Personal milestones that required grit and focus, and the times I let myself and the team down. But all of you, you amazingly big-hearted crew of employees and guests, were always there to pick me up.”

It was a surprisingly candid public reflection as his Kenmore Square establishments took their last gasps—something that Harker says felt both necessary and “therapeutic.” But the restaurant closures wouldn’t be the only problem he faced that year. Only a week after the closings were officially confirmed, it was announced that the quartet behind Island Creek Oyster Bar and the Row 34 chainlet was splitting up; Sewall and Gregory would carry the Row 34 name forward, as would Bennett with Island Creek. What happened? Their public statements had the ring of a veteran rock band splitting over vague creative differences, and Harker says today that the four-person partnership simply ran its course. The divorce, he says, “was amicable enough.”

Some close to the situation, though, suggest Harker was undervalued by the outsize egos he had made equal partners in the restaurants. There are also rumblings that the foursome’s relationships never recovered from the demise of Les Sablons in Cambridge, which lasted only one year. (Sewall, Bennett, and Gregory declined an interview about their history with Harker but provided amicable statements offering well-wishes and gratitude for his work.)

Whatever the case, Harkertown had been mostly dismantled within a matter of days. At least Harker found a considerable measure of comfort in the success of Eastern Standard Provisions, a snack brand he cofounded in 2019 that’s anchored mainly by artisan pretzels sold to fans by mail, at bars and breweries, and at national retailers like Costco and Whole Foods. In its first year, sales reportedly skyrocketed by more than $15 million after Oprah Winfrey named the pretzels to her famous “Favorite Things” list.

Still, it was a rough few years that led to a lot of soul-searching and self-reflection for Harker. “When it became crystal clear that I was losing Kenmore, I called my mom and was like, ‘I have nothing, Mom.’ She was like, ‘Oh, thank God. Now you can finally figure out what you want to do with your life.’ I was 51 years old, and she was not being funny.”

At least at home he had his partner, Laura Addezio, a sales manager at Boston’s Four Seasons, and their two-year-old son. They helped Harker get through it. “It was a test. It was really hard,” he says now. “If I didn’t have a two-year-old, I’m not sure what direction it could have gone in,” he says. “It could have gotten really dark.”

Instead, he decided to walk toward the kitchen light.

Harker says returning to the Fenway-Kenmore neighborhood is more about proving something to himself than anything else.

It’s a humid summer day, but thirsts are being quenched inside Narragansett Brewery. Even wearing blue jeans, Harker stands out as all business amid the hipsters filing in for after-work trivia. He’s in the house to sample the Eastern Standard–branded pilsner he’s developed with the Rhode Island beermaker. Cans haven’t yet rolled out; we’re taste-testing the suds straight from the tap. As a starstruck ’Gansett brewmaster looks on (with “butterflies” in her stomach, she gushes when Harker is out of earshot), he lifts the sample-size glass, inspects it as though it’s wine or whiskey, and tips it to his lips.

“Mmm!” Harker approves. The brewmaster beams.

Once upon a time, making beer probably wouldn’t have been a priority for a fine-dining restaurant GM. But it certainly makes sense for the now-king of pretzels in Boston, especially in an era when a diverse portfolio of projects is essential to survival in the hospitality business.

The former Eastern Standard awning. / Photo by Lane Turner/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Still, great restaurants remain the bread and butter for Harker, who still operates Branch Line in Watertown. So when developer John Rosenthal approached him about bringing his Midas touch to the Bower, he couldn’t resist the opportunity to resurrect Eastern Standard Kitchen & Drinks and add a few more concepts to his portfolio. “Every single major developer in the city wanted him,” Rosenthal says. “And he chose to restart his career in the neighborhood that made him successful.”

To that point, Harker says returning to the Fenway-Kenmore neighborhood is more about proving something to himself than to his old landlord down the street. In fact, he passed on the chance to open in a space even closer to his old Hotel Commonwealth address. “I looked at a space, and I’d be lying if I said I didn’t go home and think, I want to open that space just so I can crush those guys.”

“But in the end,” he says, “that’s not the right reason. It’s not a great motivation.”

What is, he explains, is re-staking his claim in the neighborhood he was instrumental in transforming. “This is my neighborhood. This is my identity,” he says. “Yeah, I opened up other spots in different neighborhoods I loved, but the way I constructed my company, Eastern Standard was the anchor. It’s hard to find somebody who wakes up every day more motivated than I am to reset things.”

Expectations are high, of course, and as the industry continues to navigate the post-COVID landscape, it’s likely many will look to Harker as a leader as he charts his next chapter. Ask him how he feels about Boston’s dining scene today, and he’s not shy: Prices have gone up, and everything else has gone downhill. “I can name 10 of the hottest restaurants in New York right now, places you can’t even get into, that are cheaper than six restaurants I won’t name in Boston,” he says. “I feel like the diner is getting the short shrift. For the first year [of the pandemic], all of the industry initiatives were about what we as restaurateurs were entitled to. But the industry is trying to hold on to that post-COVID, and I’m sick of it. Restaurants are just flat-out gouging people and not delivering on the other end.”

For someone who revels in the role of educator, though, Harker is keeping his own promises humble. He says he’s not interested in reinventing the wheel with his latest restaurants, and he doesn’t intend to open any more. But in an era when the dining scene in Boston is becoming increasingly corporatized and bland, Harker is confident there’s still a place for the magic of Eastern Standard—and, in turn, the restaurateur himself. “I need the city,” he confides as we sip our beer. “And the city, I think, needs me.”

First published in the print edition of the October 2023 issue with the headline, “Garrett Harker’s Big Comeback.”