Why I Left the Boston Ballet

After a career-threatening injury, professional dancer Isaac Akiba decided to break out of the performing arts' insular bubble. Here's what he learned by finally joining the real world.

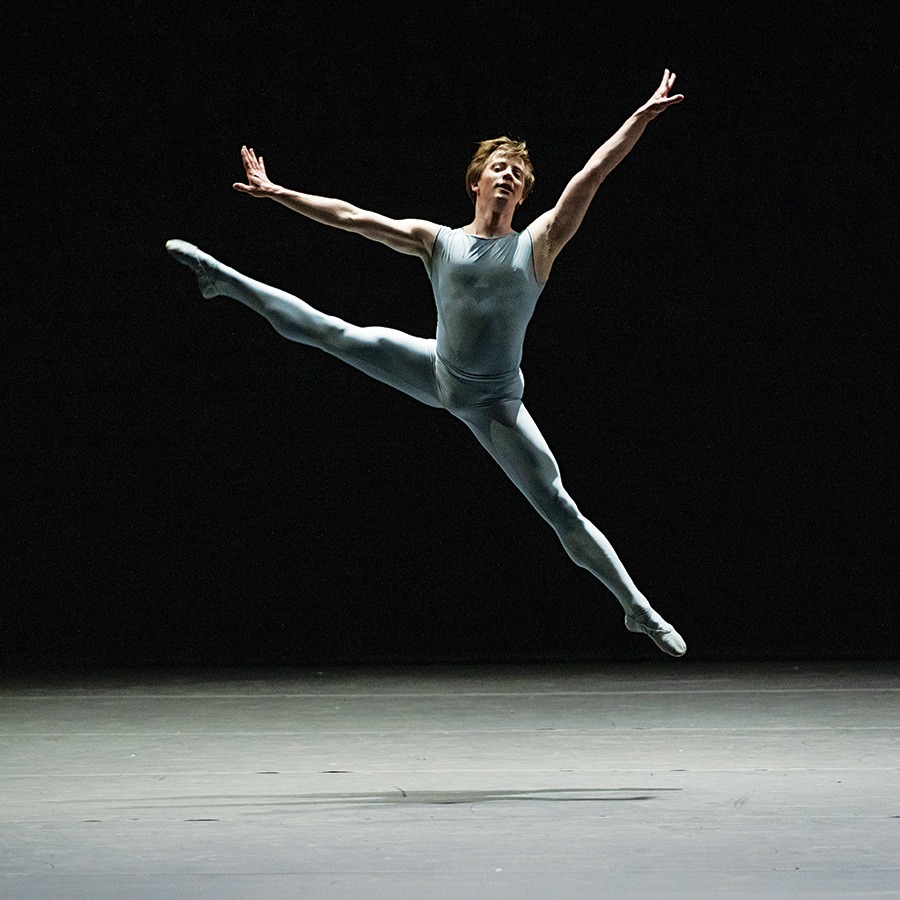

Photo by Ken Richardson

Standing in the wings before the curtain lifted for the third and final act of The Sleeping Beauty, I became acutely aware of the backstage bustle. A puff of white particles hovered over a ballerina’s ankles while she dug and twisted her toes into a box of rosin. Another dancer, with eyes closed in focused meditation, adjusted her tutu while prancing to keep warm. A male dancer’s eyes stared forward in concentration, unphased by members of the crisscrossing production crew hurriedly making last-minute adjustments to the backdrop.

I’ve witnessed this backstage scene hundreds of times throughout my 15-year-long career at Boston Ballet, where I went from an apprentice to a soloist. I’ve performed in more than 90 productions across 10 countries and three continents alongside the world’s most accomplished dancers.

In the past, I’d managed my pre-show nerves by warming up backstage and going over my steps. Yet this time, I just stood still at the perimeter of the stage while my colleagues twirled past me. My body felt stiff and cold. Everything felt different. This performance would be my last.

I fell in love with dance because of the craft itself. Ballet demands an exacting and technical approach, which complemented my personality even from an early age. The stage offers freedom yet discipline, creativity yet precision. More than anything, though, I was enamored with the idea of striving for the impossible feat of attaining perfection.

That was me. That was who I was. That was where I felt safe. Still, during the winter of 2022, I made a decision that had once felt unthinkable: to retire from the art form I’d been practicing since I was nine years old.

A storm of life-altering events led me to that point. It started in 2019, when my father—a well-known Boston-based photographer who was my biggest fan and the person most instrumental to my success as a dancer—passed away from esophageal cancer. Four months later, my family sat in the audience watching me perform the iconic role of lead Russian in The Nutcracker. Wanting to lift their spirits through my dance, I flew out of the wings with unbounded energy. I could feel the air sweep through my hair and glide unchallenged between my fingers. A doublé saut de basque punctuates a transition into the second half of the dance, and effortlessly, I took off into the jump. When I landed in the fourth position, facing the audience, my front knee buckled. I hobbled offstage in agonizing pain and fell into the wings. The next day, an MRI revealed that I had torn a ligament in my knee.

It wasn’t solely this injury—and the complicated recovery process caused by the arrival of COVID-19—that changed my perspective on dance. While the pandemic lockdown was limiting and tragic for many people, it gave me a freedom that I had never known after spending six days a week rehearsing in a dance studio for most of my life. Instead of being told when to show up, I scheduled my own physical training sessions. Instead of being told what to do with my body, I decided how to move. For the first time in my life, I had autonomy and self-determination over my schedule. At the same time, I began exploring Judaism, something I had never done growing up in a family that was culturally Jewish but not religious. In my new circle of friends, a group of young Jewish professionals, I found a community, ideas, concerns, and pursuits that didn’t have anything to do with ballet, the only thing I had ever focused on.

Nearly two years after my injury, I successfully performed the demanding role of lead Russian dancer again. My body was back in top form, but something inside my mind had shifted and would never be the same.

I came to the difficult decision that I no longer wanted to dance. The next part, though, was harder: What did I want to do with the rest of my life? Could I find a new profession that provided as much fulfillment as dance? And most important, who was I without it?

Isaac Akiba went from apprentice to soloist with Boston Ballet during his 15-year career, which ended this year. / Photo by Liza Voll Photography/Courtesy of Boston Ballet

I was in third grade when my class at the Agassiz School in Jamaica Plain was called into the school’s auditorium. One by one, we approached a woman with a tightly pulled-back ponytail seated in a chair. When it was my turn, she asked me to stand on the balls of my feet. I performed her request, and she nodded in approval. Was there something special about my toes? Later that day, I was sent home with a large white envelope containing an invitation to participate in Citydance, a free, 10-week introductory ballet course at Boston Ballet’s South End headquarters.

A few months later, my ballet class went to see Boston Ballet’s production of Don Quixote. I hadn’t known until then that the basic ballet movements I was learning in class could lead to what I was seeing on stage. Walking through the exit doors after the performance, my eyes were still wide with awe at the explosiveness of the male dancers’ movements, and my skin tingled from the vibrations of the orchestra. I tugged on my teacher’s sleeve. “Can I learn how to dance like that?” I asked. I was just 10 years old, but I could feel the trajectory of my life being set in motion.

In the early years of my dance studies, my natural ability fueled my progress. I could jump and turn with ease, and my physique fit the aesthetics of the art form. Still, even as I entered my teenage years and my ballet training intensified, I didn’t feel committed to making a profession out of dance. On the weekends, instead of focusing on pliés and tendus, I skipped class and chased girls. My teachers grew frustrated. Getting kicked out of class was also a weekly occurrence. I would sit by the door to the studio and wait to be called back in.

It wasn’t until my most soft-spoken and gentle teacher sat me down after missing a Saturday-morning class that I realized the mistake I was making. It was the first time I had heard her irritated. “Isaac, you must choose,” I recall her saying. “Do you want to be a professional ballet dancer?” Until that moment, no one had asked that question—not even me. I realized that if I didn’t snap out of it, I would be forfeiting an extraordinary opportunity. I owed it to myself to be present in my classes and try my best.

The author (far right) performing “Fancy Free” in front of the USS Cassin Young in Boston, one of three separate dances that were a part of the Boston Ballet’s “Genius At Play” season opener in 2018. / Photo by Barry Chin/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Things quickly turned around, and at the end of that school year, I skipped to the next level. At that point, I was also studying dance in high school at Boston Arts Academy in the Fenway, and it caused some scheduling conflicts. My family and I made the difficult decision that I would drop out of high school.

Now that I could spend all day at Boston Ballet, I single-mindedly poured all of myself into dance. My technique and artistry grew exponentially. I was regularly chosen to perform the leads in the school shows and began to work with the professional company.

One day, when I was 16 years old, the director of the school pulled me into her office. “Isaac, you have more skill than some of the dancers in the professional company,” she told me. “It is almost certain that you will be offered a job.” I felt that my dream was almost within reach.

Two years later, in 2007, I received another large white envelope. This time, after nine years of training, it was an invitation to join Boston Ballet as a professional dancer. On opening night of my first production with the company, the cast approached the audience to take our bow. With my body inclined and beads of sweat cascading onto the floor, I inconspicuously looked to my left. Standing next to me was Larissa Ponomarenko, the longtime prima ballerina of Boston Ballet. At that moment, I knew I had made it.

Over the next 12 years, I consumed myself with ballet. I danced four to six hours a day, six days a week. All my friends were dancers. My roommates were dancers. I took extra summer dance jobs; I trained others. I barely knew the world outside the confines of my ballet bubble. I didn’t think of anything else besides dance.

Ballet was my world. Until it became my prison.

In November 2021, my knee had healed enough to make my triumphant return to The Nutcracker, but my feet were overwhelmed with pain from weakened bones that made it difficult to walk. And after having gained a new community through Judaism, on Friday nights and Saturdays I now wanted to observe Shabbat rather than perform. Learning Jewish wisdom with friends felt longer-lasting compared to the fleeting satisfaction after a good show. I also found I had less patience for the lack of autonomy over so many aspects of my work and life that being a ballet dancer required.

Raw feelings of wanting to break free overwhelmed me. I wanted to learn something new. I wanted a different challenge. I wanted a different life. In May 2022, I requested a meeting with the ballet’s artistic director and told him that the next season would be my last.

I realized that 25 years of ballet didn’t just teach me how to soar through the air and spin like a top; it taught discipline, hard work, and perseverance—skills I could take with me when I left.

After that meeting, I spent several weeks researching and thinking about what would come next. I had recently earned an undergraduate degree, which I’d pursued at Northeastern in parallel with my dancing career, and decided to apply to business school. When the 2022 season ended in June, my decision hit me. My way of life for the past 25 years was coming to an end.

As I thought about the standardized test for which I would need to study, the essays I would need to write, and the new skills I would have to acquire to complete my applications, my thoughts spiraled. Could I do it? And if I could, would I even get into business school? My heart started racing and my vision blurred. I sunk into the couch and clasped my sweaty hands. Soon, I was having a panic attack. It was the first time I had ever had one, and it was my brain’s way of sending hazard signals, of letting me know I wasn’t okay. The attack only lasted a few minutes, but a stress that deregulated my entire being persisted for months.

Still, the anxiety over this new phase of my life was coupled with something else: a sense of urgency to do something new. I realized that 25 years of ballet didn’t just teach me how to soar through the air and spin like a top; it taught discipline, hard work, and perseverance—skills I could take with me when I left. Skills I could use right then. I sat at my desk for four to six hours a day until I finished my business school applications.

Left to right: Akiba with John Lam and Jeffrey Cirio at a 2013 dress rehearsal of Boston Ballet’s Chroma at the Boston Opera House. / Photo by Yoon S. Byun/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

I returned to the ballet in the fall for my final season. On an early-October day, when I was walking to Stony Brook station on the way to a day of rehearsals, my phone rang. I glanced at the screen; it was an unknown caller. My heart skipped a beat as I swiped to answer. I immediately recognized the woman’s voice as the administrator who had conducted my interview. “Hello, this is Boston University’s Questrom School of Business calling to inform you that you’ve been accepted into the class of 2025—congratulations!” I was beaming. That morning, for the first time in as long as I could remember, I couldn’t feel any pain in my feet as I walked down the cobblestone streets of the South End.

It was challenging to finish the ballet season. I was ready to move on, so instead of feeling sorrow as that chapter of my life was coming to an end, I felt free. Free to embark on a new chapter. I was eager to say goodbye, and happy I was doing it on my own terms. After seeing many dancers forced to quit after an injury, I felt grateful that I would have a farewell performance.

The night of that performance, I walked onto the stage for the curtain call to wild applause and flowers flying at me as I took my final bow. I felt a mix of emotions. But mostly, I felt gratitude for having been part of such a beautiful art form for so long.

A week later, I went back to Boston Ballet to empty my locker. At the bottom was a large white envelope. I tossed it in the duffel bag along with my array of accumulated things. As I walked through the building, I saw the studio where I fell in love with dance. I saw where I had my first crush. I saw where I accomplished my dreams and developed into a well-rounded person. Boston Ballet wasn’t my second home. For so long, it had been my home.

I decided to exit through the side door, because it was the door I’d used when I first entered the building as a student in the 10-week introductory program. Outside, I stopped and wondered what was in that large white envelope. Was it a superfluous form from human resources? I took it out of the bag, opened it, and slid out its contents: five black-and-white photographs signed by my dad. I had tucked it away years earlier after telling my Citydance story to a local news outlet. The first photo was of me at my very first Nutcracker audition. The rest were of me as a young boy at some of my first classes with Boston Ballet.

As I stood there on Clarendon Street, I felt like my dad was standing with me. Reminding me, as I leap into my second act, of the joy that little boy felt when he first discovered something he loved to do.

First published in the print edition of the October 2023 issue with the headline, “Making the Leap.”