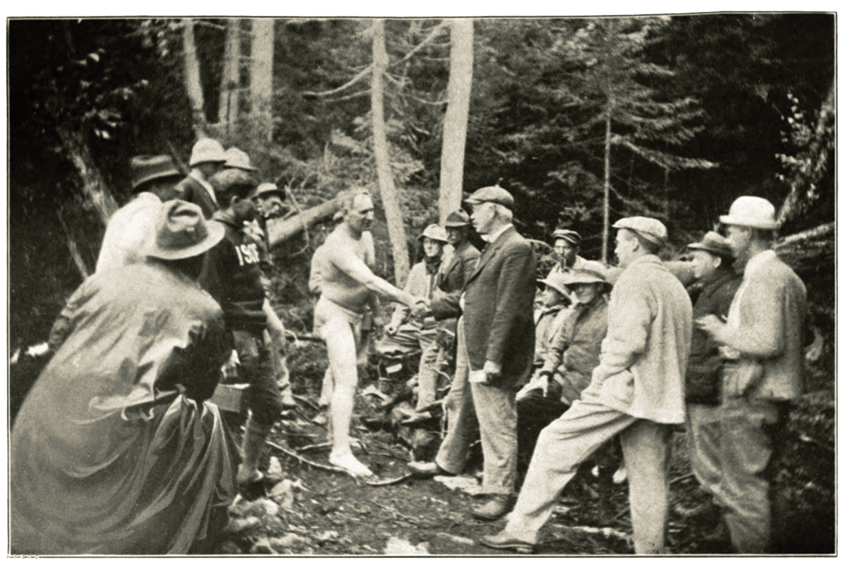

Naked Joe

A stripped-down Joe Knowles on August 4, 1913, saying goodbye to well-wishers before heading off on his Maine wilderness adventure.

At first, as the train rolled into North Station on that crisp autumn morning a century ago, it looked like the police might lose their rein on the mob. There were an estimated 200,000 people on hand to greet the world’s most unkempt celebrity, Joe Knowles, who was arriving from Portland on October 9, 1913. Men stood atop railroad cars, waiting. Female admirers lingered by the tracks, hoping for a private audience with Knowles, who, according to the Boston Post, had just completed “a most extraordinary experiment never before attempted by civilized man.” The stairs to the subway were so crowded that they resembled a “grandstand at a football game,” the Post would report, and the crowds spilled out onto Causeway Street and around the corner onto Canal.

The throngs first spied Knowles sitting beside the window of the train’s drawing room. A middle-aged man with an unruly gray beard and a long tangle of gray hair, Knowles was no Adonis. Indeed, he was a bit portly, at 5-foot-9 and 180 pounds. His muscle tone was about what you’d expect of a 44-year-old professional illustrator with a predilection for hanging about the taverns of Boston, where he regaled the boys with exuberant tales of his glory days—the 1890s, when he worked as a trapper and hunting guide in the woods of his native Maine. His gut hung. His arms bore some flab. Still, a few days hence, 400 coeds from Dr. Sargent’s Physical Training School for Women, in Cambridge, would stand in line waiting for the chance to touch his worn skin. Now, the crowds simply surged. Scores of policemen endeavored to hold them back as they rushed the train, and for a moment it seemed that chaos would erupt. This was a happy and civilized moment, however, and soon Knowles’s fans stopped shoving and began bellowing cries of affection. “Great work, Joe!…You’re all right!…You’re my bet!”

Then Joe Knowles emerged from the train, wearing a crude bearskin robe and grimy bearskin trousers. It wasn’t a costume, exactly—Knowles had established himself as the Nature Man. Two months earlier, he had stepped into the woods of Maine wearing nothing but a white cotton jockstrap, to live sans tools and without any human contact. His aim? To answer questions gnawing at a society that was modernizing at a dizzying rate, endowed suddenly with the motor car, the elevator, and the telephone. Could modern man, in all his softness, ever regain the hardihood of his primitive forebears? Could he still rub two sticks together to make fire? Could he spear fish in secluded lakes and kill game with his bare hands? Knowles had just returned from the woods, and his answer to each of these questions was a triumphant yes. In time, he would parlay his Nature Man fame into a five-month run on the vaudeville circuit, where he would earn a reported $1,200 a week billed as a “Master of Woodcraft.” He would publish a memoir, Alone in the Wilderness, that would sell some 30,000 copies. He would even have his moment in Hollywood, playing the lead in a spine-tingling 1914 nature drama also called Alone in the Wilderness.

Knowles was the reality star of his day. On the Sunday after he set off, the Boston Sunday Post ran a whole special section on him, complete with a banner headline reading, “Naked as Cave Man He Enters Woods.” There was a ponderous studio portrait of him (he appeared in profile, with his head bowed as smoke plumed skyward from his cigarette), and there was also an affidavit, signed in cursive by 17 witnesses, affirming that Knowles had entered the woods at 10:40 a.m. on August 4 “alone, empty-handed and without clothing.” In an adjacent think piece, the Post quoted Dr. Dudley Sargent, the founder of the Physical Training School for Women, and also the “physical director” at Harvard. “His attempt to live like primeval man will have a scientific value,” Sargent declared. “We will be interested to know how the lack of salt will affect Knowles.”

Knowles would soon become an asterisk of history. For now, though, after he emerged from that train, he followed the police out into the streets, then stepped into a waiting automobile for a parade. As the car began to move, he stood up, and pandemonium ensued. “Those nearest to the machine,” the Post reported, “threatened to smash the running boards as they mounted the rims and mud guards.”

Eventually, Knowles reached Boston Common, where as many as 20,000 people were waiting for what, presumably, would be the most critical speech of Knowles’s life—the one public address that would distinguish him in the annals of American history.

Knowles climbed out of the car, made his way to the bandstand, and began to speak. “I will tell you one thing,” he told the crowd. “It is a whole lot easier being in the woods than it is making a speech.”

He made a couple of vapid remarks. Then he got back in the car.

Joe Knowles lived in the golden age of publicity stunts. In 1901 a woman named Annie Taylor became the first person to descend Niagara Falls in a barrel. In 1911 Ralph “Pappy” Hankinson, a Ford dealer in Topeka, Kansas, invented the sport of auto polo to sell Model T cars. In 1924, to promote a movie, Alvin “Shipwreck” Kelly sat atop a high pole outside an L.A. theater for 13 hours and 13 minutes, launching a short-lived American craze for flagpole sitting. According to a condescending and scathing 1938 New Yorker story on Knowles, the Nature Man stunt was dreamed up by Knowles’s drinking buddy, Michael McKeogh, a freelance writer. McKeogh read Robinson Crusoe and marveled over how the book, published almost two centuries earlier, was still selling briskly. Then, one night in 1913, in a smoky Boston saloon, as McKeogh listened to Knowles ramble on about his long-ago Maine adventures…light bulb! In his mind’s eye, he saw old Joe naked in the woods. “We’ll make a million,” he told Knowles. Then he drafted an outline of the drama (and of a prospective book) onto a notepad. “Tuesday: kills bear,” he wrote, then asked, “But are you sure you can do it, Joe?”

Hunched at the bar, Knowles described five or six ways that he could.

Knowles had recently worked at the Boston Post, a sleepy workingman’s newspaper that was trying to stay alive in the nation’s most competitive media market. The city had 10 daily papers in 1913, and the Post was bleeding readers to the flashy upstart Boston American, which was financed by William Randolph Hearst, the father of yellow journalism. Knowles met with the Post’s Sunday editor, Charles E. L. Wingate, and proposed that the paper could boost readership by sending him to the Maine woods. He promised to produce drawings and status reports on birch bark, using charcoal, and to leave the documents in the crook of a designated tree. Hunting guides could then fetch them for McKeogh and other reporters, who would linger near Knowles, in a small cabin, and cast the whole tale as a fine, purple-tinged melodrama.

Wingate said yes to the scheme and agreed to pay Knowles a now-forgotten sum. His decision would prove brilliant. Between August and October 1913, the Post would later report, its circulation rose from 200,000 to more than 436,000.