Brigham and Women’s Researchers Growing Bones with Clay

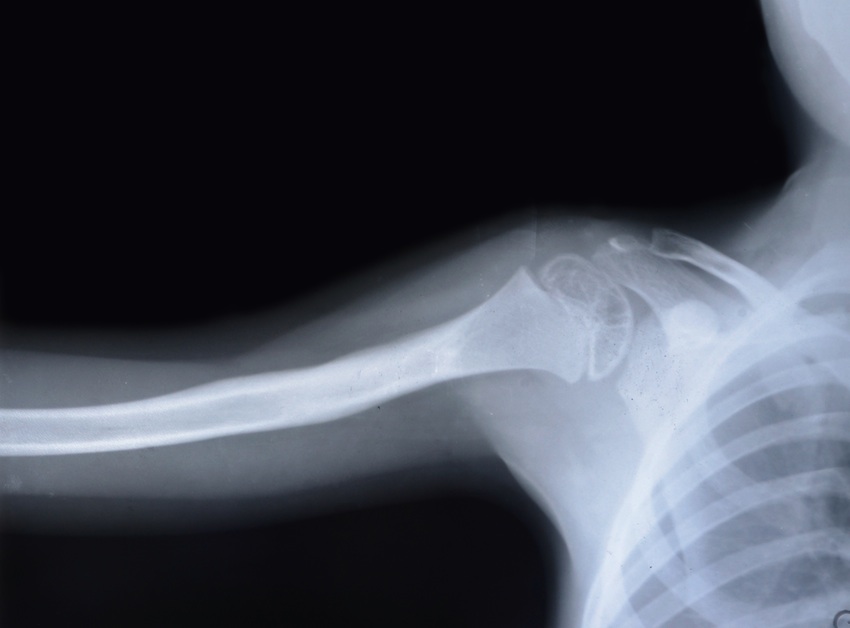

Shoulder bone image via Shutterstock.

If you thought that clay was just something you used in elementary school art class, think again. Researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital are now using it to grow bones.

In a study published in May by Advanced Materials, Ali Khademhosseini, PhD, of the Biomedical Engineering department at Harvard Medical School and the study’s lead researcher, reported that layered clay (or more technically, synthetic silicate nanoplatelets) can turn bone marrow stem cells into bone cells. Previous to this study, the synthetic clay had been used for food additives, glass and ceramic fillers, and even anti-caking agents.

Dr. Khademhosseini is excited about the synthetic clay’s potential to repair human bone, and in a report for Brigham and Women’s says:

“With an aging population in the US, injuries and degenerative conditions are subsequently on the rise. As a result, there is an increased demand for therapies that can repair damaged tissues. In particular, there is a great need for new materials that can direct stem cell differentiation and facilitate functional tissue formation. Silicate nanoplatelets have the potential to address this need in medicine and biotechnology.”

During the study, researchers combined the clay with human stem cells in a variety of settings. The first setting included an interaction with a steroid that is known to promote tissue growth, and the second setting consisted of a steroid-free environment. On day 14, the researchers saw bone growth in both settings, which showed them that the clay could help grow bone with or without another agent. Not only that, but the clay promoted bone growth more quickly than the steroid itself, which usually takes 21 days to show any sign of new tissue.

According to the report, this research could lead to the possibility for injectable forms of tissue repair and therapy, or even the ability to stimulate specific cells in response to tissue problems and broken bones. With MIT’s recent creation of 3-D printed artificial bones, and Brigham and Women’s ability to grow bones with clay, broken bones could soon be a problem of the past.