Q&A: Peter Brady, Designer for the New England Aquarium

Peter Brady stands in his Charlestown studio. (Photo by Margaret Burdge)

As fish weave in and out of crevices and penguins slide into the water from their indoor habitat, neon lights draw viewers toward the center of the New England Aquarium at the newly renovated Giant Ocean Tank. A year ago, the aquarium closed its central exhibit, removed the penguins, and promised to be back after renovations. After only a couple months of being reopened, the fish are reproducing well, attendance is booming, and the masterpiece just a couple of finishing touches away from complete.

When looking at the giant coral reefs and seamless structures within the habitat, it’s hard to imagine that this was once an empty tank. Despite its lifelike resemblance, viewers are not looking into a natural ocean scene; each crevice was created and assembled thanks to the talented hands of Peter Brady, the New England Aquarium’s lead architect of more than 30 years.

While walking through his dust-laden Charlestown studio—where the aquatic magic gets created—Brady explained the year-long journey that led the aquarium to where it is today.

There are a lot of parts that go into a profession like this: you have to be artistic, you have to understand the animals, and the biology. How did you come to do this?

It’s an unusual line of work. There’s no specific training—it’s kind of hodgepodge. It combines artistic ability, [there are] structural and building trade aspects to it, and you’ve got to be able to build things and work with a different people. Scientific knowledge helps. In the exhibit world, people tend to come from a variety of backgrounds. Most people in this field would have come from some kind of arts or building trades background. My college training was in environmental science and biology, and I minored in art. I just gravitated to science-related artwork.

You’ve been with the New England Aquarium long before this renovation. What precipitated the redevelopments?

The building opened in 1969 and basically, there hadn’t been any repairs or upgrades since it opened. The whole tank was due a facelift. It was time to replace the windows, and it was time to investigate where the structure weakened and repair that. The environment in the tank had been installed around 1984, and it was getting old and worn. Algae accumulates, things break, general wear and tear.

What are these things made of so that they resist wear and tear? So the algae doesn’t cover it and they don’t fall apart in the aquatic habitat?

Everything’s artificial. It’s mostly fiberglass, basically plastics and urethane. The structure itself that you see is a fiberglass shell. It’s hollow and texturized to look like rock, but it’s fiberglass—way lighter. Another way to do an exhibit like this is with concrete. Concrete is hosed and poured in, and it’s carved and sculpted to look like rock. There are advantages and disadvantages to that, but one thing is that it’s very heavy. If we had done the exhibit that way, the weight would have become an issue. We already had a fiberglass structure that was very sound so we built on that. We kept what was good and changed what needed to change. It was nice to start with a basically sound structure—that was a big advantage.

The aquarium itself is such a staple of Boston, and the fact that you got this done so quickly—and with the aquarium still open—is really impressive. Was that hard to accomplish?

The Giant Ocean Tank is the centerpiece of the aquarium, and to do the project, the penguins [around the tank] also had to be off exhibit. With the noise, the dust, everything else… [Penguins’ respiratory systems] are very sensitive—they needed to be off exhibit. So here we had probably our two most popular features unavailable to the public for a pretty long time, so it was a challenge. We made the assessment that the project could be run without closing the aquarium, so that’s what we did. It required very careful project management, and to do that level of construction inside a building while it was open to the public was remarkable. The whole project is closing out now. Basically it ran on schedule and we’re more-or-less on budget.

You try to make the habitat architecture as realistically accurate as possible. Is that for aesthetic benefit, the benefit of the animals, or just what you personally like to do?

All of the above. If you reproduce the environment that the animals on display live in naturally, it just enriches their behavior, enriches their life. It’s like an “everybody wins” kind of thing. It’s better for the animals and better for visitors. When the animals are in the backdrop of their natural environment, it just enriches the whole experience. Sometimes it makes it harder to see the animals, because they can hide, so that’s a challenge. You try to design the habitat so it provides refuge, but also so they’re not totally hidden.

You said you kept a lot of features that were already in the exhibit and then updated it with some of the new ones. What is the most noteworthy change that has been made?

In general what I wanted to do was create interesting mini-environments that were close to the windows. If you’re at the tank and you walk up or down the spiral, you’ll notice that pretty close to the window are these interesting formations. They’re magnets for small fish because they create this really interesting refuge. But then you can see past it to the expanse of the tank, where there are large fish swimming. Basically, we were able to just embellish the amount of real estate where fish could find little, new homes.

Is this working out well for the fish, does everything fit?

One really gratifying thing was that most of what you see is all sort of married, integrated. But we had a few free-standing structures. There are flat, sandy, plate areas like platforms, under which animal cages can be placed for introducing animals. After divers lowered them into place, fish just started gravitating to them, so that was very gratifying.

What are you working on now?

At the bottom of the spiral there was an area for children called the Curious George corner. That was removed in construction, so we redesigned that into a touch-sculptural area of coral. We’re just finishing up that, and this is basically the last significant part of the whole project.

Brady created 3,000 new pieces to add to the exhibit, along with the “facelifts” he gave to 80 percent of the existing corals. (Photo by Margaret Burdge)

The wall in Brady’s studio is covered with images of the corals he is looking to create. (Photo by Margaret Burdge)

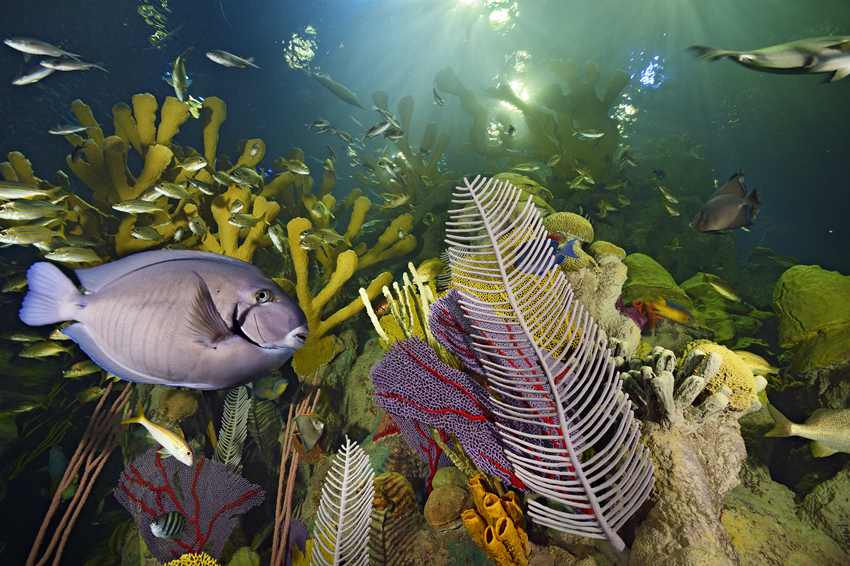

Haven’t gotten to the aquarium yet? Here are some pictures of the redesign Brady engineered. (All photos provided)

The Giant Ocean Tank towers above the African penguin exhibit at the New England Aquarium. (Photo by W. Chappell)

The new and improved Giant Ocean Tank at the New England Aquarium contains nearly 2,000 animals, including more species of Caribbean fish than ever before. (Photo by National Geographic photographer, Brian Skerry)

Feeding time is almost all the time in the newly renovated Giant Ocean Tank. (Photo by W. Chappell)