What’s Next for Boston Ballet Director Mikko Nissinen?

The first-born child (he has a younger brother, Antti) of a ceramicist mother and painter father, Nissinen grew up middle class in Helsinki, encouraged by his parents and his grandfather, a clarinetist, to pursue the arts. In 1973, at age 11, he joined the Finnish National Ballet’s first all-boys class. Soon he befriended a 12-year-old classmate named Jorma Elo. With money scrounged from roles as extras, the boys traveled to Copenhagen to see Baryshnikov perform live. “It was a transformative experience,” Nissinen told me. He returned to Finland dedicated—“I was a slave to ballet for the next 20 years,” he said—and became a professional in the Finnish National Ballet at 15. But even then he envisioned a post-dance career as a director. “I was young when I realized I wasn’t the next Baryshnikov,” he said. “But I kept studying my director and would catch myself thinking, I would do this differently. I would do that differently.”

In 1998, Nissinen was named the director of the Alberta Ballet, in Calgary. Three years later, the Boston Ballet offered him a job. “It was an easy decision,” he said. “I was being asked to join the big leagues. Sure, a big-league team with a lot of problems…. But when you’re new, you have a lot of immunity to achieve what you want.” To begin the process of achieving what he wanted, he fired six dancers before he even arrived in Boston.

After settling in town, Nissinen purchased two floors in a South End townhouse and planted a Japanese garden. (“I’m very scissor-happy with my bonsais,” he said.) He quickly became known for his ferocious work habits. Barry Hughson, the current executive director of the Boston Ballet, recalled the time Nissinen offered to take him out on his boat, Koi. “I had the idea that we’d throw a line out and have a few beers,” Hughson told me. Instead, Nissinen arrived at his house at 4 o’clock in the morning. “And then,” Hughson said, “from the moment we got on the boat to the moment we got off, it was work.”

Nissinen extended each of the day’s dance classes. And he demanded that nearly every performance of every ballet be taped and reviewed. Then he set about recruiting dancers from across the globe.

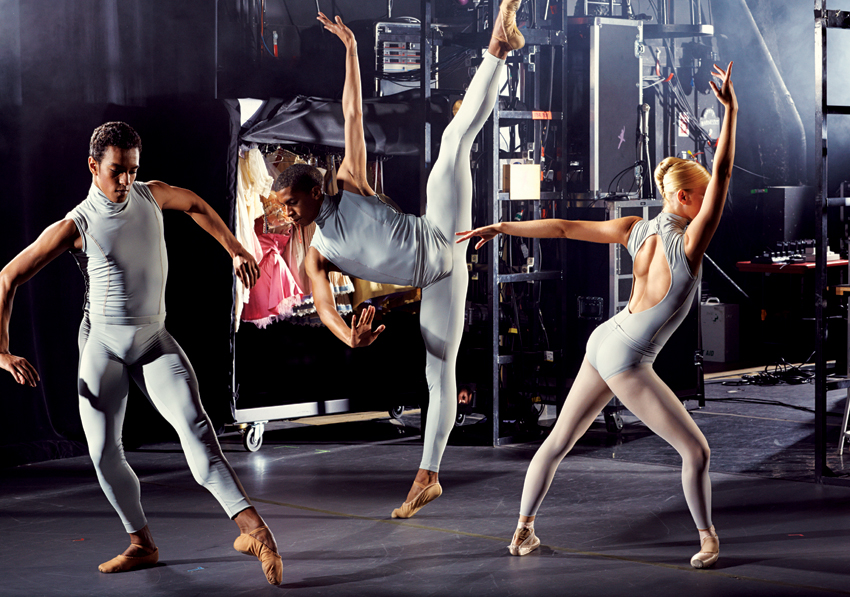

Early on, Nissinen told me, “elitist” season subscribers and a few board members would lecture him on what to stage, whom to cast, or how to act. “Someone,” said the director known for his all-black attire, “even told me, ‘You should wear blue ties. It makes you look more confident.’ As you can see, I didn’t take their advice.” His disregard for convention wasn’t limited to his wardrobe. In 2002 Nissinen commissioned his childhood friend Jorma Elo, then an unknown choreographer, to craft a world premiere. Elo came back with Sharp Side of Dark, which featured an abstract series of pas de deux, break dancing, and gymnastics in simple gray unitards. “A lot of people around me said, ‘Oh my God, you can’t do that. Audiences won’t get it,’” Nissinen told me. When the trustees raised objections, he recalled, “I would tell them, ‘I have no idea what you’re talking about.’” Sharp Side of Dark premiered in September of that year and quickly drew both catcalls and rave reviews. It was then that Nissinen decided, “Enough with what people have said. I’m going to push the envelope.”

Nissinen also ignored typical ballet hierarchy. Rather than assign the top roles to principals, he often gave them to less-senior members of the corps de ballet. “He didn’t hold on to traditional conventions about having to pay your dues or your time,” said Heather Myers, who is one of three dancers Nissinen brought in from Alberta, and who danced with the Boston Ballet from 2002 to 2009. Not everyone liked these changes. Several dancers, including Romi Beppu, Ashley Blade-Martin, Alfonso Martin, and Sarah Lamb, quit because they felt snubbed. Jennifer Gelfand, a principal ballerina since 1989, told me that her roles diminished soon after Nissinen joined the company. When she left, she told the dance critic Christine Temin, “I wasn’t going to stay around and be miserable trying to find out what he wants.”

Many of the dancers who did stay could sympathize with those who did not. Valerie Wilder, who served as executive director from 2002 to 2008, said Nissinen’s sole directorial weakness, “which could also be seen as a strength, is his single-mindedness in achieving his artistic goals and, one could almost say, ruthlessness. He has achieved great things at Boston Ballet, but at a human cost.” Myers recalled that just before one of her first performances, Nissinen told the dancers to abandon the idea of performing “nice and safely” on opening night. “He insisted on the opposite, that we completely go for it with everything we had.” Lia Cirio, a principal dancer, told me that “The way he designs our repertoire pushes our strengths and weaknesses. We go from one week of crazy contemporary classes and then the next week relearning classical as Aurora in Sleeping Beauty. Every day is an audition.” (In recognition of the physical demands his style can place on dancers, Nissinen has renovated, and added staff to, the Boston Ballet studio’s health and wellness center.) But Cirio and other dancers who have remained with Nissinen told me that the unrelenting battery of classes and rehearsals fosters a sense of family. During the Chroma performance, every dancer remained close to the wings while offstage, cheering on their colleagues and even playfully flipping them off—an inversion of the toxic backstage culture depicted, for instance, in the movie Black Swan. Nissinen, however, remained hidden in his seat throughout Chroma.

In 2004, just as Nissinen was establishing himself as the most dexterous and visionary director in the Boston Ballet’s history, catastrophe struck. The organization in charge of the 3,600-seat Wang Theatre decided that, instead of the Boston Ballet’s Nutcracker, it would run the Radio City Christmas Spectacular. Even more than most companies across the country, the Boston Ballet depended on its annual Nutcracker run for an outsize percentage of revenues—30 percent, compared with 20 percent for the Washington Ballet, and 16 percent for the Joffrey Ballet, in Chicago. Ousted from the Wang, and forced into smaller venues, the company lost $6 million in two years. A sudden $3 million gift (the largest single donation in the company’s history) from the former trustee Beatrice Barrett helped stave off disaster, but the company was still underwater. “Our whole existence was threatened,” Nissinen said.

In public, however, he and executive director Valerie Wilder treated the eviction as though it were an opportunity. “We didn’t want to look as if we were about to go under,” Wilder would later tell Temin for her 2009 book, Behind the Scenes at Boston Ballet. The truth, Wilder told me, was that the duo had always planned to wean the company off its “dangerous reliance on one source of income.” Nissinen swiftly staged a less-expensive Nutcracker, but made no amendments to his forward-looking plan. “I knew what I was doing,” he said. “If I changed course, that would look even more alarming.”