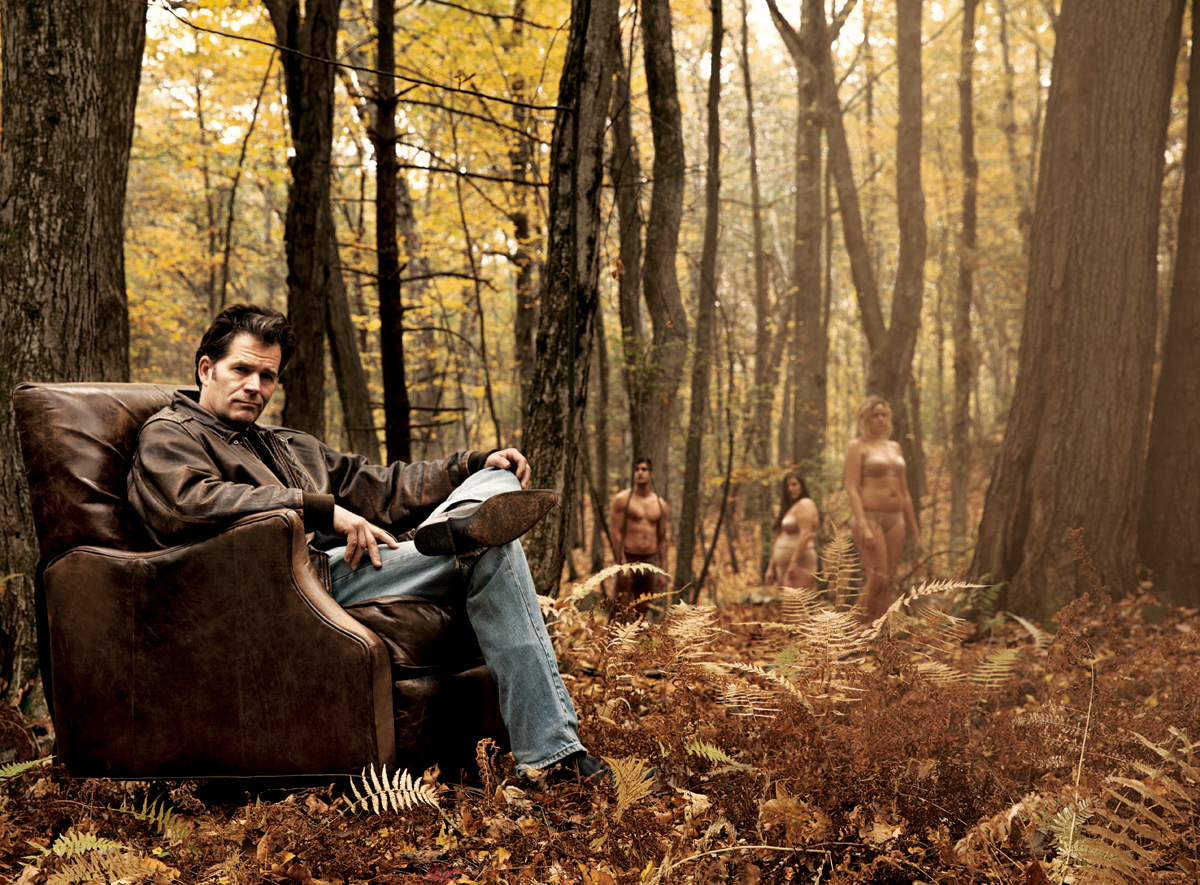

Baser Natures: Andre Dubus III Profile

Photographs by Silja Magg. Shot on location at Ould Newbury Golf Club. Chair provided by Urban Elements. Models, Kayvon, Elizabeth, and Kelsey/Maggie Inc.

The area in the woods next to the shed had already been cleared of brush and the earth was raw and damp and the air smelled like the dark green of ripped leaves. Andre Dubus III, in the first stages of building an extension onto his shed, passed me a bottle of bug spray and headed from the driveway of the house he built with his brother in Newbury, into the shade where the shed stood. “You’ll need this,” he said. Fat horseflies buzzed and got swatted; mosquitoes, at around two on this breezy August afternoon, either weren’t awake, or were deterred by the spray. Dubus held a tape measure and a notebook for measurements. He surveyed the space. “I’m starting to get really excited,” he said.

The shed as it stands now used to be a stable, and houses the tools of what used to be Dubus’s trade. A quick peek in the door, with a breath of cut grass, grease, and dust, showed a tangle of cords, drills, saws, and nail guns, heaped and crowded. Standing on the wet dirt where he’d cleared much of the brush, he passed the dumb end of the tape and told me to hold it there against the wall above a joist as he moved toward the back end of the shed about 18 feet away, stretching the tape between us. As he measured, he called out the numbers and made notes on a pad for the materials he would need: Two-by-tens, two-by-twelves, pressure-treated six-by-sixes, footer tubes, hangers, lags, J-bolts.

A certain hesitation marked his movements, the tentative steps of someone moving through a once-familiar house at night after a long time away. Once, before he had become a bestselling novelist whose characters were portrayed on the big screen by the likes of Ben Kingsley, Dubus had been a self-employed carpenter. But aside from helping a nephew do some framing in a basement around Christmas, he hasn’t been building much lately. He looked like he missed it. Dubus has the lean strength of someone who pays close attention to his body, not in a showy Los Angeles way, though there is something of Hollywood about his thick wavy hair, brown with some gray at the edges. He mentioned more than once a 10-mile road race he’d completed a few days before. At age 53, he ran a mile in nine minutes and 55 seconds.

He made another measure, this time from the side of the shed out into the dirt and plant debris. We were talking about the language of carpentry, the slang and the nicknames, the idiosyncratic terms of measure.

“I bet your boss doesn’t use the phrase CH,” he said. My boss is a 47-year-old lesbian carpenter who I’ve been working with for about four years. “You know CH?”

It took me a second.

“We used to say, ‘Take a red CH off that board,’” he went on. “That’s a thirty-second of an inch. My wife just told me that red pubic hair is thicker than black. So we had it all wrong.”

The odometer in Dubus’s workhorse pickup truck read 206,000 miles. It was still summer, and hot, and as we climbed in and began the ride over to the lumberyard to get materials for his shed extension with the windows up and the air conditioning on, we started talking about sex. His new book, Dirty Love, out last month from W. W. Norton, is a collection of two short stories and two novellas. It is a darkly sexual book, though Dubus claimed not to have realized it until recently. “I guess there is a lot of sex in that book,” he said. There is.

It’s a departure in form from his last few books, although his work has always dealt with the baser acts of human nature—in particular, violence. In his novel House of Sand and Fog, a finalist for the National Book Award that was made into an Academy Award–nominated movie, the violence is directed inward, as characters attempt (and succeed at) suicide. The Garden of Last Days takes place at a Florida strip club just before September 11, 2001; James Franco had signed on to direct a film adaptation, but over the summer he reportedly walked away just weeks before it was slated to enter production. In Dubus’s memoir, Townie, he wrote about the rough episodes of his youth, and about his attempts to put his past as a brawler behind him. The violence in Dirty Love is the emotional kind, and Dubus is glad about it. “I’m beginning to get a funny insight: By writing directly about the physical violence I had in my life as a young guy, I may have freed myself to write about something else,” he said. That’s not to say that the emotional violence is any less brutal. It’s territory his father, the masterful if underappreciated short-story writer Andre Dubus, explored with peerless strength and insight.

Two of the pieces in Dirty Love deal with infidelity: In one, a bartender and wannabe poet cheats on his pregnant wife with a busty red-haired waitress in a scuzzy seaside bar. The project manager of the opening novella watches a video of his cheating wife receiving oral sex after a workout from another man. Another story centers around the romantic and sexual compromises and disappointments of a heavyset 29-year-old virgin bank teller named Marla. In the title novella, teenage Devon tries to rise above the shame of an explicit cell-phone video of her posted online.

In the acknowledgments, Dubus thanks his 18-year-old daughter, Ariadne, for her help with understanding Facebook and cyberspace. “I would not have written that story if I didn’t have a teenage daughter,” he said. Dubus has deep concerns about the Internet, not just about the trance of the screen and ignoring one another in restaurants and as we walk down the sidewalk, but about online pornography. Growing up, he explained, he was lucky to find a moldy Playboy under a bush somewhere. “Now kids can push a button and see a woman having sex with a donkey. It’s toxic, and we don’t talk about it enough and it’s doing a real number on young men and how they view women,” he said. He’s not a prude, and emphasizes that he’s a supporter of the First Amendment. But when he talks to his sons and his male students about pornography, he tells them “porn will make you look at a woman like a sex object. Don’t do it. There’s nothing wrong with masturbation and erotica, but our brains weren’t wired for such easy access to these images. It’s like crack cocaine, and you’ve got to walk away.”