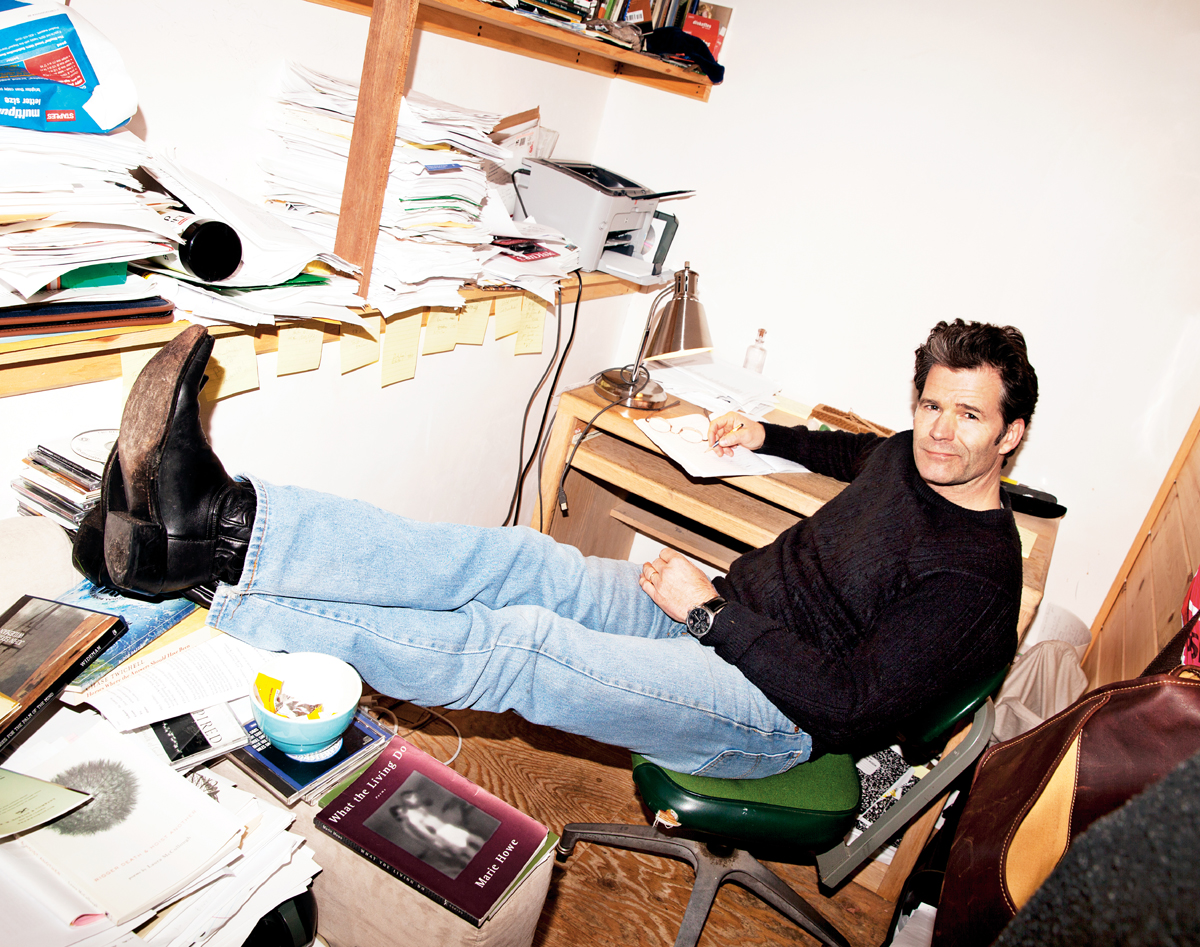

Baser Natures: Andre Dubus III Profile

“I’ve been talking to my kids about building,” Dubus said. “It’s just such a wonderfully blessed way to live, to make things.”

At the lumberyard, Dubus has an easy rapport with the folks who work there. This was the place where he got his materials when he was building his house. It’s changed hands, but a few of the older guys remain. He asked after their families. Rick, an older guy about to take a few days off for knee surgery, asked if he could have a part in the movie version of The Garden of Last Days.

“I’m saving you for a nudie scene,” Dubus joked to easy laughter.

Out back, loading the truck with the boards, Dubus scrutinized each board, the type of builder who checks each piece of wood himself. “Nope,” he said as he looked down the edge of a bowed two-by-ten. “Nope,” to another. “This one’s good. I’ll take this one.”

Dubus, like a beloved pastor or a favorite uncle, has a way of finding common ground with the people he talks to. He and Dwayne, a young guy who worked at the lumberyard, who Dubus hadn’t met before, became fast friends as Dubus selected his boards and they loaded them onto his truck.

“Friday night, you got a watering hole you go to, Dwayne?”

They talked local pubs for a few minutes: the Grog, the Thirsty Whale. Both agreed that Ceia was a little upscale. I wouldn’t have been surprised if Dwayne admitted something intimate, about his mother having Alzheimer’s or his girlfriend moving out. Such seems the effect Dubus has on people. He and Dwayne shook hands on parting, wished each other a good weekend. Dwayne’s bashful smile gave the sense that this was a good way to close out a Friday afternoon in summer.

And the scene repeated itself a few minutes later, at a natural-foods store with its smell of seeds and powders and teas, fresh fruits and the promise of clean living and its rewards, where Dubus bought a couple of protein bars. The kids behind the counter recognized him; a gray-haired guy came in the door and the two greeted each other with a handshake. He knows everyone, and everyone knows him. He passed along bits of gossip and quick bios throughout the afternoon—that guy’s wife, I think she’s his third, used to dance with Fontaine. The woman at the hardware store, her brother is a beautiful chef in town; there goes my painter, I get my windows painted every year; see the guy in the garage there? He’s a carpenter, too. I’ve worked with him before.

The truck ran sluggish and a little lower to the ground, with a bunch of pressure-treated boards and eight sacks of concrete, at 80 pounds each, weighing down the bed. He drove through the center of Newburyport, with its old brick mill buildings and narrow streets. Tents lined the main square, the smell of sausage and peppers mixed with the sweet earthy smell of roasted nuts, and a rock band was starting to warm up to a crowd of people gathered in front of the stage. It was one of the last days of Yankee Homecoming, an annual weeklong festival that brings thousands of tourists to the town.

“I’ve been talking to my kids about building,” he said as we moved slowly through town back toward his house. His 16-year-old son, Elias, is reading House of Sand and Fog, and he wanted to talk to him not about writing, but about “making things.” He told Elias that he wrote House in notebooks sitting in the front seat of his car, and if he hadn’t written in those notebooks, they wouldn’t be in the house where they live. And the house started as a drawing on a piece of paper, and now it exists in the world, and the novel that allowed him to build the house started as a sliver as an idea in his head and now it’s in 25 countries. “It’s just such a wonderfully blessed way to live, to make things,” he said.

Back home, he recruited Elias, wearing a faded Led Zeppelin T-shirt, to help him unload the truck. Broad and tall with blond hair and big shoulders and a good firm handshake for a teen, Elias told his dad about his workout that day. When his back was turned, Dubus turned to me and made a gesture that said, Can you believe this kid?

“It’s easier if you throw the bags up on your shoulder,” Dubus said as Elias lifted another bag of concrete. “And try not to breathe in the dust.”

“Too late,” Elias said. “The shower I took was totally pointless.”

“You want to help your old man with this shed?” Dubus asked him.

Elias gave him a shrug and a noncommittal maybe, probably a little more interested in fall sports and his rock band, and headed back inside the house.

Dubus was reminded of a story from back when he was five or six years old, before his parents split. His aunt was visiting, his mother’s only sister, and she asked him, “Do you want to be a writer like your daddy?” And Dubus said, “No, I don’t wanna be a writer. I wanna be a working man like Pappy.”

“And I became both.”