Spring Arts Preview 2014

Lake Street Dive: Conservatory trained, YouTube approved. / Photograph by Jarrod McCabe

The Good, the Bad, and the Lake Street Dive

Davids Letterman and Remnick may love them to death, but America’s newest roots-pop sensations are still Bostonians at heart. —Maura Johnston

It’s a cold February Friday in Harvard Square, but inside the Sinclair, on Church Street, the room is ablaze. The capacity crowd is here to celebrate the Boston-bred band Lake Street Dive’s second album, Bad Self Portraits (Signature Sounds), and it’s a kind of reunion—these fans have been with Lake Street Dive since the beginning.

“I think all of us have loved playing in Boston, but especially now,” says bassist Bridget Kearney, whose skill on the upright gives the group’s live show extra swagger. “[Our] new audience knows us for a certain small window of our band history, and going back to Boston, there are people in the house who know all of our first songs from 10 years ago. So that’s awesome.”

Ah, yes, that “new audience.” Lake Street Dive—Kearney, vocalist Rachael Price, trumpeter/guitarist Mike “McDuck” Olson, and drummer Mike Calabrese—have experienced quite the whirlwind over the past two years. Though they’ve been together since the early 2000s—they met while attending the New England Conservatory of Music—their big break came in 2012, when a video of the band standing on a Brighton street corner became a YouTube sensation, as did the covers-heavy EP, Fun Machine, that accompanied it. That video—a sultry, single-mike cover of the Jackson 5’s “I Want You Back,” with lightly brushed drums, upright bass, trumpet, and the group’s devil’s-food-cake harmonies—sums up a lot of Lake Street Dive’s appeal, placing their conservatory training at the front in an almost modest way that didn’t overshadow the song’s fundamental melodic appeal.

“The central reason why we call ourselves a ‘pop band,’ and what appeals to us [about] pop music, is the immediacy of it—the visceral appeal,” Kearney says. “We’re not trying to make music that is fundamentally super-challenging to listen to. That’s not the first goal for us. We want to make music that people are going to enjoy, and that’s going to be pop…ular.” She laughs.

T-Bone Burnett was one of the people who took notice of the band’s alchemical abilities, and he invited the band to play at New York’s Town Hall last September as part of the “Another Day, Another Time” concert. The show, which celebrated the Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis, had a ton of Big Apple–based tastemakers in attendance—including New Yorker editor David Remnick and a Letterman booker. Lake Street Dive laid down a performance of “You Go Down Smooth,” a swinging Bad Self Portraits track about being drunk on bad love, and the raves rolled in. “Amy Winehouse by way of Michael Jackson,” Remnick called it—an assessment that’s in line with the band’s pop outlook.

“We’re influenced by pop music from a bunch of different eras,” Kearney says. “One of the things people hear most in it is some of the more retro pop music we’re into—the Beatles, Motown. That’s definitely some of our favorite music to listen to, so it makes sense that those sounds would be present in our music. But we’re also into a bunch of current music—Beck, the Dirty Projectors, Rubblebucket.”

Bad Self Portraits splits the difference among a handful of classic pop idioms. Price’s velvety voice has just enough grit—and the arrangements are just crisp enough—for Lake Street Dive to do double duty at cocktail bars and rock clubs. Each member has a hand in writing the skeletons of songs (Kearney, for example, wrote the heartbroken title track), but the band’s workshopping process involves collectively arranging both the track and—crucially—the vocal harmonies, which curl underneath Price’s enigmatic purr in ways that make them sound plush. “I think that adds a coherence to a collection of songs that are written by four different people,” Kearney notes.

After playing to a series of sold-out crowds across America this spring, Lake Street Dive will come back to Boston for a show at Royale, a sprawling downtown palace that’s quite a ways from the band’s scruffier beginnings. “We did some of our first shows at Toad, in Cambridge,” Kearney recalls. “It’s just a perfect, tiny dive bar where we learned how to be a band. Now that we’re playing bigger venues, I sometimes imagine myself still in Toad to get into the right place. Toad and the Lizard Lounge and Club Passim were the clubs in Boston that really took us under their wing when we were first getting started, and we’re so grateful to the people who run those spots.”

On that Friday in Cambridge, gratitude flowed back and forth—the audience sang along with Lake Street Dive’s originals and covers, while the band declared from the stage that it still considered Boston its hometown. Later on, after the bar closed, the band would make its Late Show with David Letterman debut. They threw down a performance of Bad Self Portraits’ title track that caused the notoriously sardonic Letterman to ask them if they’d be interested in coming back “every night—can you do that?” Given Lake Street Dive’s increasingly tight schedule, the residency offer probably wouldn’t work out. But the idea of them bringing something new to the Ed Sullivan Theater stage night after night isn’t too farfetched.

Lake Street Dive plays April 6 at Royale, 279 Tremont St., Boston, lakestreetdive.com.

POP

Festivals, homecomings, and triumphs of “local losers” help Boston thaw after a long, cold winter. —Maura Johnston

Photo Provided

The Both, The Both

(SuperEgo, out April 15)

In 2012, Ted Leo and Boston new-wave icon Aimee Mann toured together and later began collaborating as #Both. They’ve since dropped the hashtag from their name and recorded a briskly smart, self-titled full-length. The combination of Mann’s precise songcraft and Leo’s punk-honed chops is a delight; The Both is crisp and wry, full of well-appointed pop songs in which Mann’s sullen, muscular alto provides a grounding counterpoint to Leo’s rich tenor. Bonus: Their onstage rapport should be in even finer form by the time they hit Boston in April.

4/25, Paradise Rock Club, 967 Commonwealth Ave., Boston, the-both.com.

Pile, “Special Snowflakes”

(Exploding in Sound)

You know you’re making waves when other bands are writing songs about you. Earlier this year, local noise-pop outfit Krill put out “Steve Hears Pile in Malden and Bursts into Tears,” a valentine of sorts to the effects of this quartet’s shoulder-shaking, scene-beloved rock. Even Pile’s slower jams inspire aggressive moshing: the lead song from their new single, “Special Snowflakes,” trades quiet guitar interludes with screamy freakouts until it screeches to a halt. It’ll turn Great Scott into a combination mosh pit/ballet studio.

3/30, Great Scott, 1222 Commonwealth Ave., Boston, pile.bandcamp.com.

“New England Metal & Hardcore Festival”

This three-day, two-stage salute to face-melting metal and hardcore goes up for the 16th time in mid-April. Springfield metalcore outfit All That Remains headline day one, while renowned Boston hardcore metallurgists Sam Black Church—reuniting for their third performance of the 21st century—anchor the local offerings.

4/17–4/19, the Palladium, 261 Main St., Worcester, metalandhardcorefestival.com.

“Together Boston”

This weeklong, multi-venue “celebration of music, art, and technology” features talks, screenings, and art installations. Mos Def plays the Wilbur on May 15; the music lineup also includes U.K. dance producer Sophie. The documentary I Dream of Wires, which examines the resurgence of the analog synth, will screen at the ICA.

5/11–5/18, various locations, togetherboston.com.

Mean Creek, Local Losers

(Old Flame, out April 8)

The latest album by this feisty four-piece is the best recording to date of the undeniable energy the group brings to its raved-about live sets—imagine Springsteen headlining a basement show. The vocal interplay between Chris Keene and Aurore Ounjian is particularly arresting on the hungry “Johnny Allen,” while Kevin Macdonald’s strident bass playing provides a solid yet pleasantly loose anchor.

4/25, the Middle East, 472–480 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, 617-864-3278.

Photo Provided

Slaine, The King of Everything Else

(Suburban Noize, out June 24)

Depicting Boston’s hard-knock life on record and in film (he played the heavy in Ben Affleck’s Gone Baby Gone and The Town) comes naturally for this MC, who’s been rapping since he was nine years old. Darkness dominates his work, although he did tell the news site HipHopDX that his next album—the hyper-autobiographical The King of Everything Else—will be lighter, like “a combination of Hunter S. Thompson and Chris Farley.”

Photograph by Mike Diskin

“Boston Calling”

The third installment of Boston’s big downtown festival is a little bigger: It now runs Friday to Sunday. Early-aughts indie titans Modest Mouse and Death Cab for Cutie headline the weekend days, joined by practiced festival hands such as Hawaiian strummer Jack Johnson, heart-rending Long Islanders Brand New, and sisterly duo Tegan and Sara, not to mention new kids like Bastille and the Neighbourhood.

5/23–5/25, City Hall Plaza, bostoncalling.com.

Photo Provided

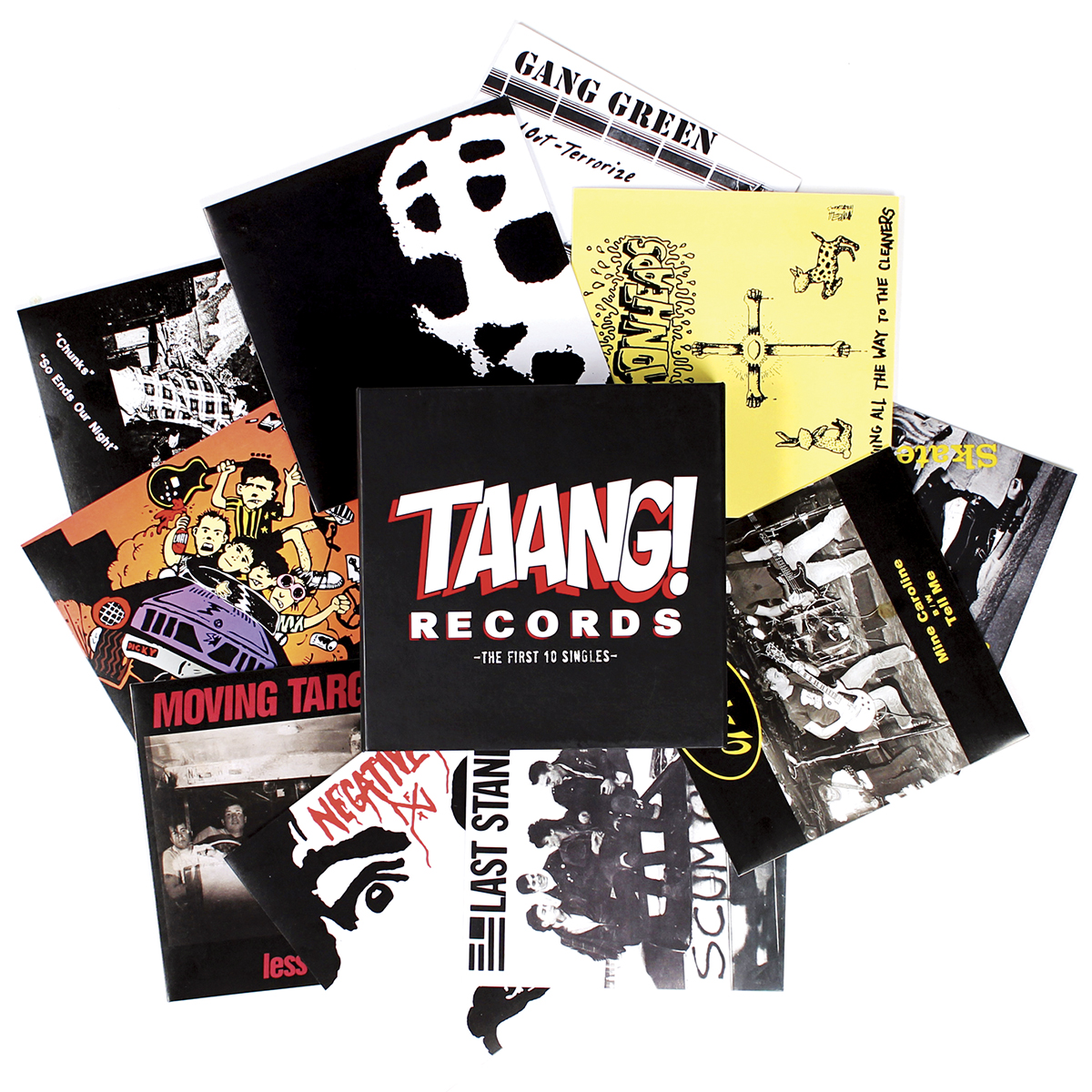

TAANG! Records: The First 10 Singles

Back in the 1980s, the legendary indie label TAANG!—a tortured acronym for “Teen Agers Are No Good”—helped put Boston’s underground scene on the map. This year, on Record Store Day, April 19, it’s coming back. The label is reissuing 10 of its early 7-inch singles—including sides by the Lemonheads, Slapshot, Moving Targets, and Gang Green—as a limited-edition, vinyl-plus-CD box set, with liner notes by founder Curtis Casella.

Photo Provided

Eli “Paperboy” Reed, Nights Like This

(Warner Bros., out April 29) Brookline-bred, Mississippi-taught retroist Eli “Paperboy” Reed gave Boston a peek at his forthcoming album, Nights Like This, when he played the Sinclair this past Valentine’s Day. The frantic “Woo Hoo” shows off his falsetto and ability to turn a wordless phrase into an incitement for a party; “Shock to the System” (co-written with Fitz & the Tantrums’ Michael Fitzpatrick) splits the difference between Sam & Dave and Bruno Mars.

CLASSICAL

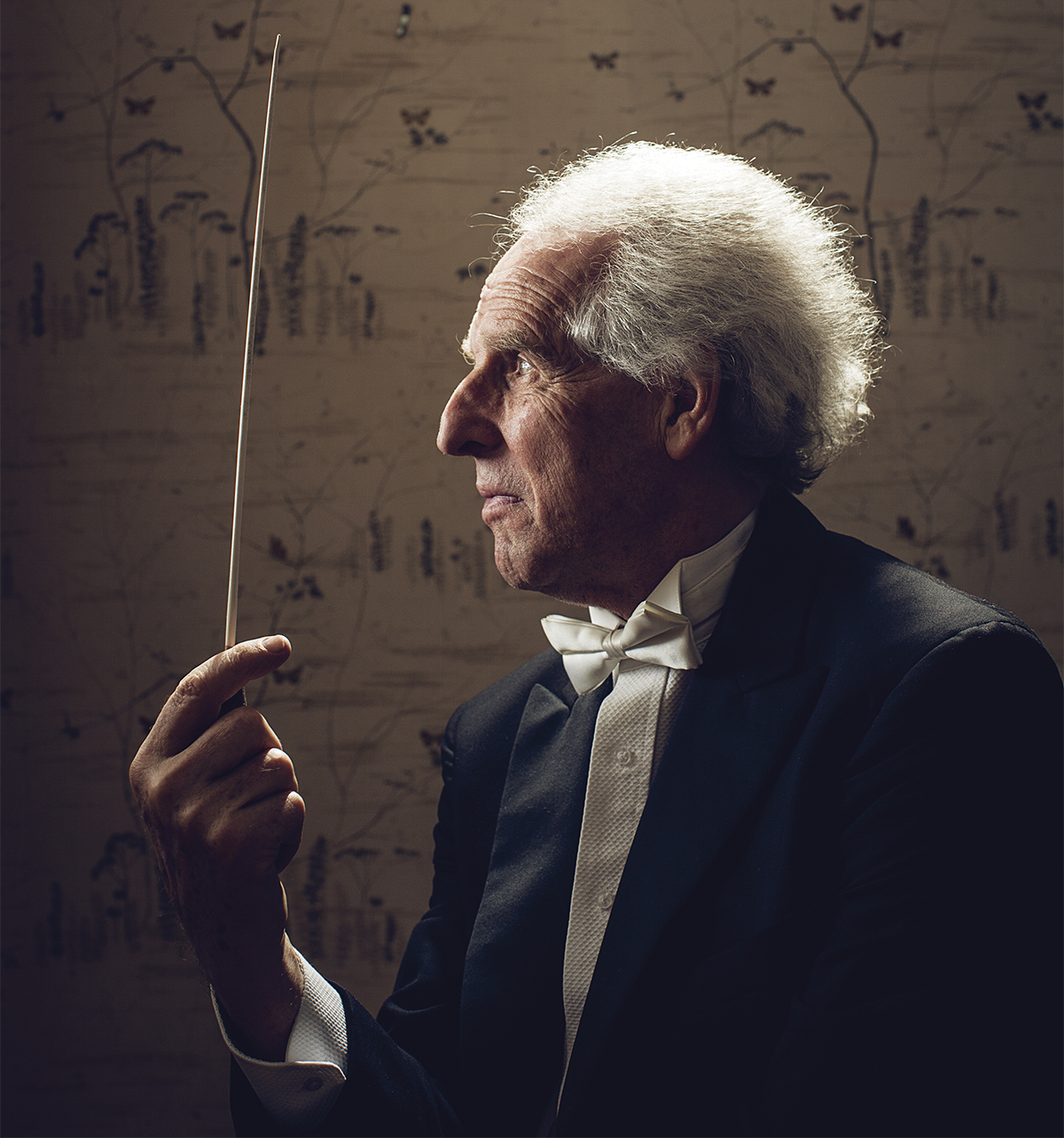

Act Two: Benjamin Zander’s return to form. / Photograph by Jarrod McCabe

The Church of Zander

Nearly sunk by scandal two years ago, the conductor is back for a vigorous second act. —Zak Jason

On a recent afternoon, Benjamin Zander stood at the prow of 117 musicians—the oldest barely legal to drink—and drove them into the stormy heart of Mahler’s Symphony No. 5. Zander growled, roared, and barked from the podium, drenched in sweat, dabbing himself with a bath towel dangling from his music stand every few minutes. Then he slashed the air with his baton, and the orchestra came to a full stop.

“This moment is a wild, terrifying tango of death,” he intoned in his British accent, addressing two pubescent clarinetists. “Can you play that again with more cojones?”

This scene would have seemed unlikely, if not impossible, two years ago. In 2012, Benjamin Zander’s career looked like it was kaput: A scandal had cost him his 45-year reign as a pedagogical deity at the New England Conservatory, and it seemed the conductor would simply fade into ignominy.

Yet here he is, on the cusp of 75, more vigorous than ever. Not only is he helming a new youth orchestra, but he is also leading the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra into its 35th season—playing Symphony Hall on April 25 and holding a celebratory gala the following night. On the side, he’s performing and guest-conducting with orchestras from Virginia to Malaysia, and giving motivational speeches to corporate executives. It’s a second movement no one could have predicted—except those who know him well.

“The wounds are still open,” says his former wife and close friend, Rosamund Zander. “But he doesn’t visit them. Ben doesn’t spend time doing pointed work on himself; he’s out there in the public.”

Born two years after his Jewish parents fled Berlin, Zander dropped out of high school at 15 and trained as a cellist under the Spanish virtuoso Gaspar Cassadó. He came to Boston in 1964 on a Harkness Commonwealth Fellowship to study at Harvard and Brandeis and wound up at NEC, where he cofounded and developed NEC’s partnership with the Walnut Hill School for the Arts. He took the program from seven students to 90, and transformed a fledgling youth ensemble into an orchestra that brought connoisseur audiences from Brazil to China to tears.

“You could try to temper him, but it wouldn’t happen,” says longtime BPO cellist Armenne Derderian. “Especially with the kids, he’s incredibly dramatic. He wants a holy explosion of fabulous music, full commitment, for you to sink yourself into the music in a way no other conductor demands.”

Former NEC student and current BPO violinist Joshua Peckins says, “He treated all of us like real musicians and real humans.”

Zander’s downfall came in early 2012. At the time, a scandal was unfolding at Penn State—after former football defensive coordinator Jerry Sandusky was indicted for decades of raping children, 46-year head coach Joe Paterno was fired in November 2011 for failing to fully report his knowledge of the abuse. This set the backdrop for the NEC administration’s discovery that a videographer Zander had hired to tape the youth orchestra’s rehearsals was a convicted child rapist. Worse, that Zander had known about the conviction before hiring him, and had even written character testimony for the man at his sentencing in 1993.

NEC president Tony Woodcock had no great love for Zander; the previous summer he had forced the conductor to agree that he would retire in 2013. Armed with the new information, Woodcock fired Zander outright on January 12, 2012. Reactions were polarized. Students picketed an NEC benefit and wrote a petition for his reinstatement. Many companies canceled his motivational speeches. Some pundits excused his behavior; other cited his “breathtaking irresponsibility.”

“Nobody gained from that,” Zander says from a seat beside his fireplace, where above the mantel sits a bumper sticker that reads: A positive attitude may not solve all of your problems, but it will annoy enough people to make it worth the effort. “And I don’t blame anybody. It was the atmosphere of the time. Everybody was so sensitive. If they thought it out a little more deeply… ” He pauses there. That’s all he wants to say on record.

But Zander has a history of snatching victory from defeat. For example, the board of the amateur Civic Symphony Orchestra of Boston fired him in 1979 for going against their edict of performing more contemporary American music. Instead, he’d persistently scheduled masterworks of Mahler, Beethoven, and Dvorak. “It was becoming the Ben Zander orchestra and not the Civic Symphony,” one of the board’s vice presidents told the Globe. Days later, however, every CSO musician joined Zander in founding the semiprofessional BPO, the group that has made him one of the world’s top Mahler interpreters.

And again, in the late 1980s, as his marriage to Rosamund fell apart, the pair agreed to attend the Landmark Forum—a three-day seminar popular among corporate executives but often lampooned in the media for its hokey insistence that participants disclose their deepest feelings. The seminar did not save their marriage, but it transformed their relationship. “Rather than getting lawyers to destroy each other, we created this new world,” Zander says. Together they wrote the self-help book The Art of Possibility (2000). Zander still preaches its message on the public-speaking circuit, where he has also become a cult figure. Today, he and Rosamund live separately, but her landscape paintings fill the walls of his home, and they speak every day.

This time, as the scandal unfolded and Zander sheltered from reporters, Rosamund and NEC colleagues in his corner convinced him to start the tuition-free Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra, a “possibility organization” that shapes both musicianship and interpersonal philosophy. He held auditions in his home. More than two dozen students fled NEC. In all 170 tried out, and Zander brought on 117. They met for the first time a year and a half ago and debuted in November 2012 with a nearly sold-out and rave-reviewed performance of Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben in Symphony Hall.

Zander begins every Saturday BPYO rehearsal with a whimsical assignment such as “Feel a spring in your step” or “Fail with spirit” and gives each young musician a blank sheet of paper to reflect on their musical and personal growth or struggles, reflections Zander often posts on the BPYO Facebook page. Since their founding, they’ve performed at the Concertgebouw, in Amsterdam, and at Carnegie Hall, a performance the New York Times called “brilliantly played, fervently felt.”

Zander’s omnipresence has also maintained his semiprofessional BPO as a serious competitor to the 133-year-old, $413-million-endowed Boston Symphony Orchestra—this in an age when most American cities strain to keep a single ensemble alive. He pumps funds from his possibility seminars into the BPO. “I’m the Robin Hood of classical music,” he says. He’s a consummate marketer: While most conductors save their energy backstage, Zander cackles with patrons in the lobby and presents deeply researched and lyrical preconcert talks. Zander often says, “My definition of success is not wealth, fame, or power. It’s how many shining eyes are around me.”

Retirement is not on the horizon. “He’s a teenager in many ways, avoiding structure, avoiding settling down,” says BPYO artistic adviser and former NEC dean Mark Churchill. “I’ll give him another 20 or 25 years, no question.”

When that happens, what will become of his orchestras? “It’s almost impossible to imagine the BPO without him,” Peckins says. “It wouldn’t be the BPO without Ben,” Schwartz says.

Back at rehearsal, Zander let the Mahler proceed for a few bars, and then cut off a woodwind solo. “Here, you’re searching,” he said, clasping his hand, as if catching a fly without squashing it, and looked up at the 40-foot ceiling. “Searching for some truth that you don’t know where to find.” When the flutists played it back, the phrase became less robotic and much more inquisitive, human.

“Ha!” he shouted as they continued.

“I’m going to spend the rest of my life here,” Zander said during a break. “They’ll take me off the stage and into a box.”