Harvard Art Museums Exhibits Pop Art by Activist Catholic Nun Corita Kent

“Boston Gas Tank (Rainbow Tank),” 1971, by Corita Kent / photo courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

In 1971, the president of Boston Gas—now National Grid—commissioned local artist and former nun Corita Kent to decorate a 150-foot-high natural gas tank facing the Southeast Expressway, which he saw repeatedly while flying in and out of Logan Airport.

Kent came up with a design that consisted of large swashes of color, which she painted on a miniature wooden model before it was transferred to the actual tank in Dorchester by professional sign printers.

For Susan Dackerman, the former curator of prints at the Harvard Art Museums, the tank is Boston’s pop art landmark, equivalent to the Hollywood sign in Los Angeles, a dilapidated real estate advertisement that Kent’s contemporary Ed Ruscha had revitalized and transformed into an iconic image with his 1968 prints.

“The conversation about the tank got derailed,” says Dackerman, referring to the controversy that followed the work’s unveiling, powered by claims that a profile of Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh was concealed within the blue stripe.

Kent, despite being a critic of the Vietnam War, denied the claim until her death in 1986—and Dackerman stands with her.

“It’s just not the way she worked,” she says.

In her exhibition “Corita Kent and the Language of Pop,” now open at the Harvard Art Museums, Dackerman places Kent’s works within the field of pop art—which art history has typically excluded her from—and seeks to elevate her from a little-recognized artist to a formidable contemporary of Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and other pop art icons.

“Corita Kent and her work are typically regarded as an anomaly,” says Dackerman. “What we wanted to do here was to take it, show it alongside the work of those better-known contemporaries, and demonstrate how well-aligned it is with [their] work, but also to show how she does something unique with pop art that allows us to broaden the definition of that style.”

The exhibition focuses on the 1960s, with Dackerman identifying 1962 as a launching pad for two reasons—it was the year that Warhol presented his “Campbell’s Soup Cans” at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, introducing the West Coast to a new pop art movement, and also the year that marked the start of the Vatican II deliberations, when the Roman Catholic Church began brainstorming ways to modernize its practices.

Both events directly affected Kent, who at the time was a Catholic nun in the Immaculate Heart of Mary convent in Los Angeles, where she also taught art and introduced students to local galleries and museums.

“She said years later in an interview that once she had seen what Warhol was doing with the soup cans, you couldn’t look at anything again without thinking about how Warhol saw the world,” says Dackerman.

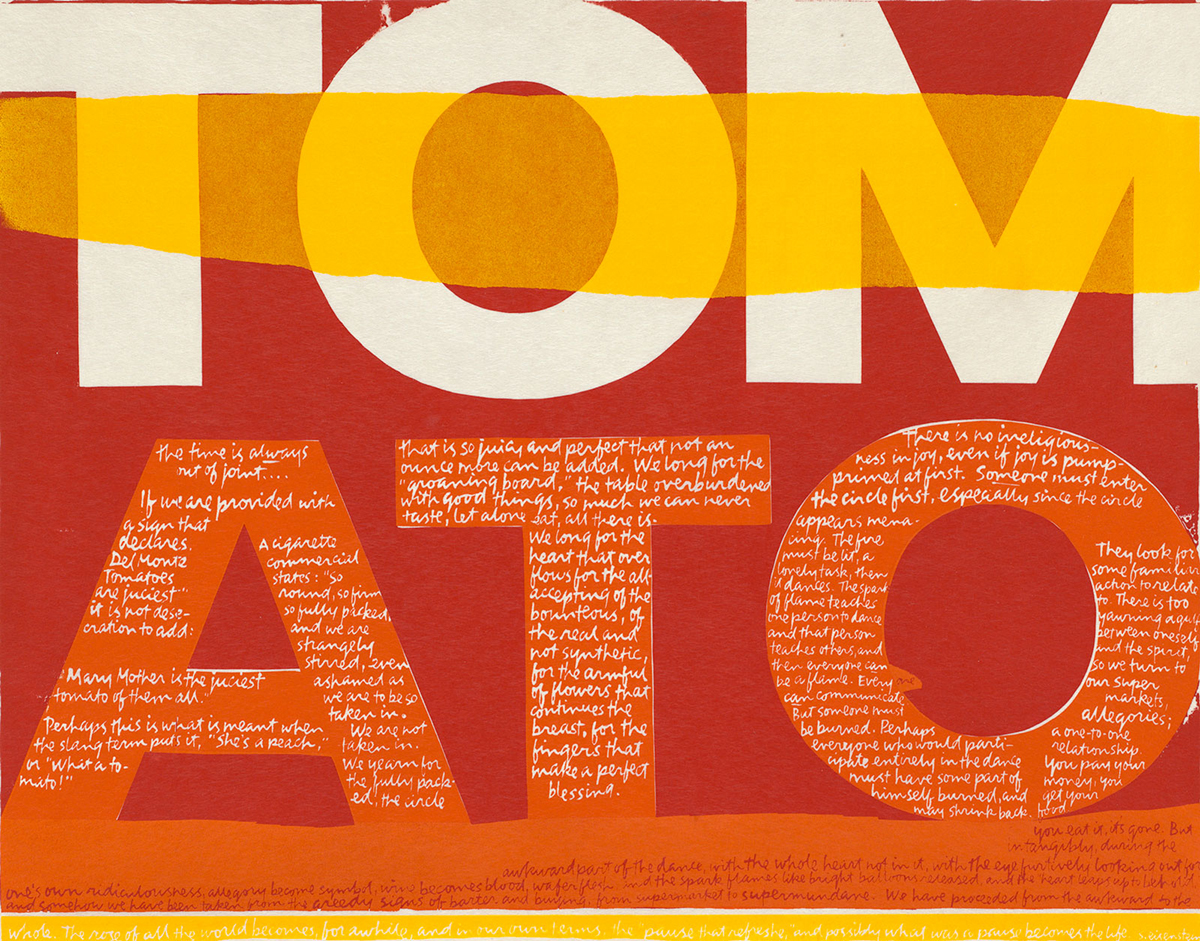

“The Juiciest Tomato of All” (1964) by Corita Kent / courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

Like Warhol, Kent began to use consumerist imagery—often drawing inspiration from her trips to the Market Basket across the street from Immaculate Heart College—in her art, which mostly took the form of screen prints.

But unlike Warhol and other artists who used images of actual products and their packaging, Kent focused more on text, repurposing slogans and catchphrases from product advertisements. Additionally, she intended for her works to serve a religious purpose—to express the ideals of Vatican II, which promoted accessibility with changes like allowing the use of local languages during Mass rather than strictly Latin.

“This was a moment of intense religious reform, a moment when, like the art of the period, the religion of the period was being popularized, and she thought that in its more relevant incarnation, it needed a new language, a new scripture,” says Dackerman. “She found that scripture in the language that surrounded her.”

In “the juiciest tomato of all,” she repurposes the slogan from a Del Monte can to serve as a tribute to the Virgin Mary. In small text that could only be read up close, she writes, “Mother Mary is the juiciest tomato of them all. Perhaps this is what is meant when the slang term puts it, ‘She’s a peach,’ or ‘What a tomato!'”

“She likens the Virgin Mary to a tomato in a language that people are going to find very familiar,” says Dackerman. “It is an iconoclastic gesture—there’s a very long history of depictions of the Virgin, but she has seen Warhol transgress the copyright privileges of Campbell’s, and so in a way, she’s transgressing the copyright of the Catholic Church’s iconography of the Virgin Mary.”

In addition to more than 150 prints—roughly half by Kent and half by her contemporaries—the Harvard Art Museums exhibition also features films that showcase the nun’s screen printing process at Immaculate Heart, as well as slides taken by Kent herself that give a glimpse of the magazine advertisements, supermarket products, and street signs that inspired her. The design for the gas tank in Boston, where Kent relocated to after leaving Immaculate Heart in 1968, is shown both on the original seven-inch model and a large photo mural.

“In Boston, we of course couldn’t end without addressing the gas tank. Everyone here in town knows of Corita’s work,” says Duckerman. “The argument that we make is that the gas tank is the culmination of a decade of working on pop art.”

“Corita Kent and the Language of Pop” is open at the Harvard Art Museums, 32 Quincy St., Cambridge, through January 3, 2016. An opening celebration, with free admission and a panel discussion, takes place on Thursday, September 3 from 5 to 9 p.m. A second evening of free admission, sponsored by National Grid, takes place on Thursday, November 12, from 5 to 10 p.m. For additional information and programming, visit harvardartmuseums.org.