Boy with a Knife Makes the Case for Justice Reform

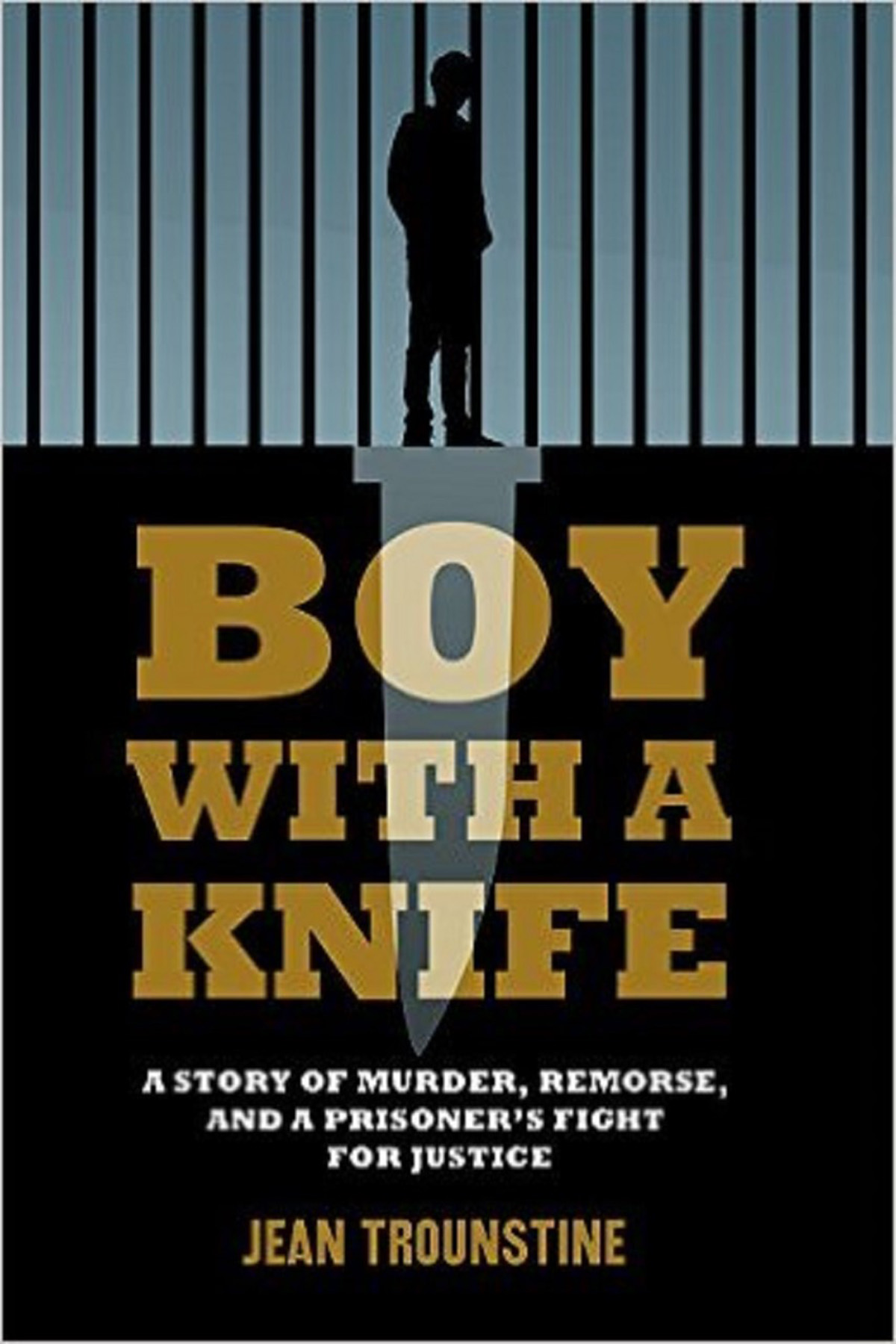

Cover image provided by Jean Trounstine

The letter came out of the blue, and it wasn’t a typical note—the envelope was marked with a somewhat ominous stamp, informing its recipient that it came from a correctional institution. When professor and activist Jean Trounstine (and Boston contributor) opened it up, she recalls beginning to shake.

The letter was from Karter Kane Reed, a convicted murderer. Reed was 16 at the time of his crime in 1993, and had been in an adult prison ever since he stabbed and killed another teenager Jason Robinson in a classroom at Dartmouth High School. After this first note reached Trounstine, a hundred more followed over a period of six years. Reed became the inspiration and subject of her new book, Boy with a Knife: A Story of Murder, Remorse, and a Prisoner’s Fight for Justice.

Boy with a Knife puts a human face to the issue of youth incarceration in adult prisons, a sector of the justice system that Trounstine argues is both broken and unjust. Her book both delves into one man’s story, and also uses his case as a reflection of what happens with countless kids across the country. It’s a broader narrative of a broken criminal justice system in which a heavy focus on punishing ignores other more effective and humane options.

Seven years after Karter’s first letter, Trounstine remembers at first grappling with whether or not to even respond. “It put me into an incredible conflict internally…At the time, I had a lot of stereotypes about men in prison,” she says. “I had all the stereotypes I tried to teach my students not to have.”

Ultimately, it was the striking way in which Reed used language that led Trounstine to pick up a pen and write him back. “It was such a contradiction to me, I couldn’t understand it,” Trounstine says. “Some part of me knew this could change my life, writing him.”

And so it did. In conjunction with regular correspondence with Reed, Trounstine, who was already involved in prison activism through her work directing plays at Framingham Women’s Prison, began to do further research into this particular subset of the justice system. The fact that children could even be sent to prison without the possibility of parole was shocking to her, and became the backdrop of her book, which makes use of both her prolific letters with Reed and her following research.

Boy with a Knife cites shocking statistics. Nearly a quarter of a million youth are tried, sentenced, or imprisoned as adults every year in the United States. Any given day sees ten thousand youth detained or incarcerated in adult jails and prisons. Trounstine forcefully argues against this, claiming it is not only unjust, but also ineffective.

“I’m hoping to add to the conversation about why laws should be changed,” she says. “I’m hoping to educate people about why kids should not go to adult prisons and jails.”

Trounstine refers to research that shows that putting kids into adult facilities doesn’t keep communities safer or help the kids. She cites behavioral research, stating that children’s brains aren’t the same as adults, and noting the dire circumstances they face in these adult prisons.

“I just think it’s a waste of so much money, lives, intelligence, chances. And it doesn’t bring back the people who were killed or the people who were harmed,” she says. “It’s why restorative justice makes so much more sense. I think that’s what we should all be working toward. Getting people to understand the consequences of their actions, not just locking them up.”

Reed himself is what drew Trounstine to pursue the subject that would become her book. “I got involved in his case because of him. Because he was so amazing,” Trounstine says. “And because I needed to answer that question—how could he be this, and how could he have done that?”

“It wasn’t until I really started to know him that I began to understand totally that he had changed,” she says.

Above all else in Boy with a Knife, Trounstine argues for opportunity. She recognizes the fact that it’ll be hard to change the law stating that children as young as 14 can be tried for murder as an adult if they are found guilty. “That’s a law that a lot of people don’t want changed,” she says.

But Trounstine is hopeful, especially when considering recent Supreme Court cases like Miller v. Alabama and Montgomery v. Louisiana that ruled a life sentence without parole should not apply to children, that change is possible and imperative.

“It’s giving them an opportunity to change. That’s what I’m arguing for. That we need to change our laws,” she says.

Trounstine didn’t know Reed’s fate when she embarked on telling his story—and the fact that he did indeed get out of prison was a twist along the way. In 2013, Reed sued the parole board and won his freedom.

“At one point I remember when he wrote me and he said, ‘You know, I might actually get out, and you would have a happy ending to your book.’” Trounstine says. “I can’t say this is a happy ending because Jason Robinson is still dead. But there is a chance for another person to make his life meaningful in the world.”

Boy with a Knife is available via IG Publishing and Amazon. A reading and signing will take place April 19 at Porter Square Books.