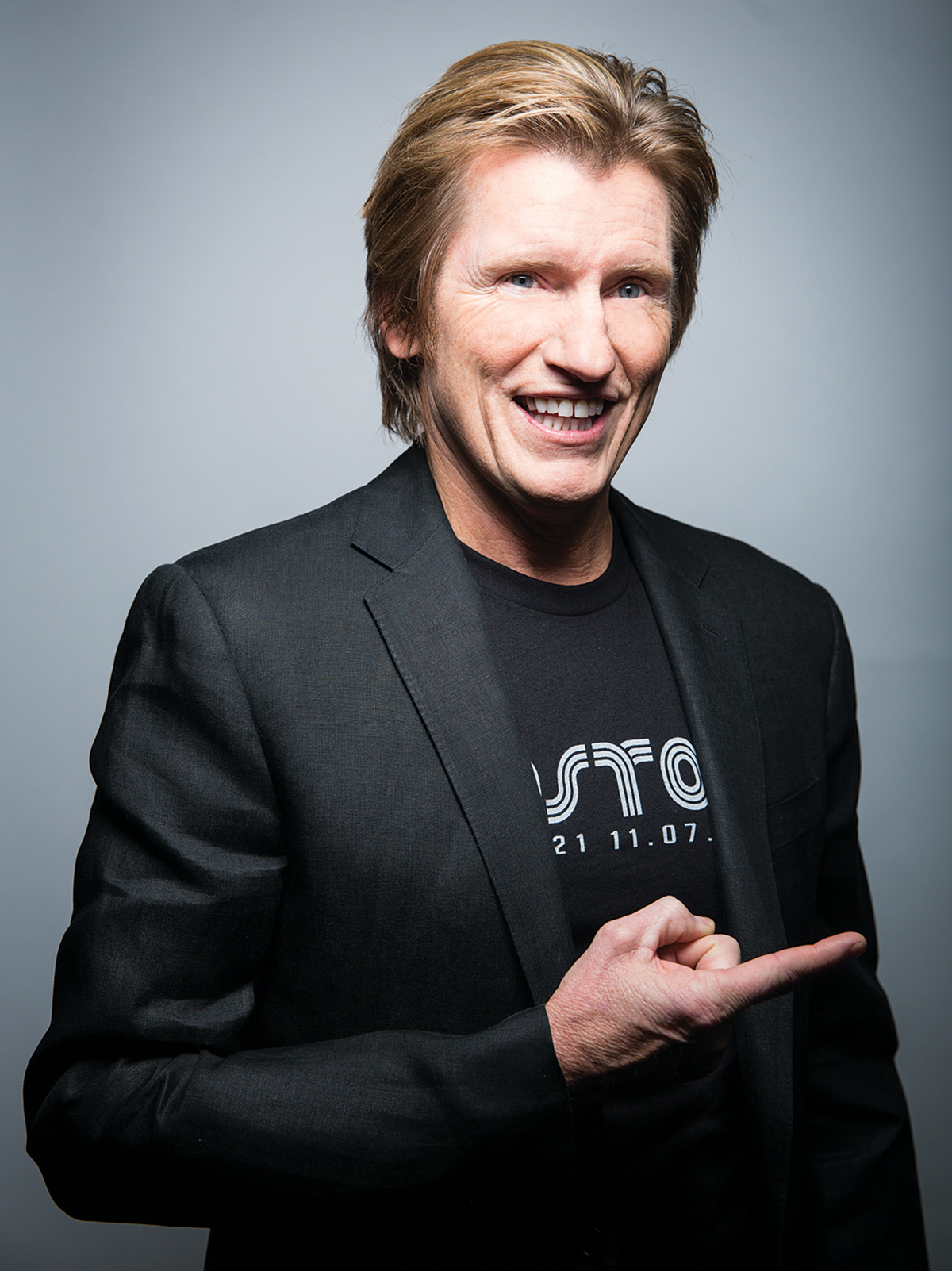

The Interview: Denis Leary

Photograph by Trevor Reid

It has been a steady, profane, and smoky rise to the top for Denis Leary, the self-proclaimed “asshole” who cut his teeth in Boston’s comedy clubs and remains one of Massachusetts’ most acerbic cultural exports. Once known for bits about cigarettes and Cindy Crawford, Leary pivoted in the early aughts to writing, producing, and starring in Rescue Me, the firefighter drama that enjoyed critical success for seven seasons. This month, the 58-year-old is back with Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll, a gonzo-esque comedy on FX in which Leary plays an over-the-hill musician still chasing dreams of stardom. After decades spent navigating the comedy circuit, Leary had no shortage of material to tap when it came time to create a character who parties like a rock star.

Your character, Johnny Rock, has said that as an artist, he needs to do drugs to write songs. When you were younger, were you ever convinced that drugs made you a better writer or comedian?

No, for me it doesn’t work. I was either unfortunate or fortunate to be around a lot of the drugs being used in rock ’n’ roll and comedy back in the ’80s, so I got to see some stuff.

Such as?

I’ll never forget this: Nick DiPaolo, a terrific comedian from Boston, and I were young and pretty much just starting out. Sam Kinison hadn’t broken through yet, but word on the street was that he was going to be a big star. So Kinison came to Boston to perform one night and Lenny Clarke said, “You guys have to come down and meet Sam and watch him perform.” And I don’t know how much cocaine it was, but Sam pulled out cocaine in the dressing room while we were meeting him—there were probably five guys in there—and it looked like he was pulling out enough cocaine for five guys. And instead, while he was talking to us, he did the entire pile, right as they’re announcing, “Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Sam Kinison.” So we watch him go on stage—and he fucking slayed. He absolutely slayed—he got a standing ovation at the end. And Nick DiPaolo and I are standing in the back of the room going, “Is that what you have to do to get good at this?” and Lenny was like, “No! This guy is a beast, this guy is a monster, he’s one of a kind. You don’t want to do that.”

In Rescue Me it was easy to empathize with the characters because they were firefighters—a profession most people root for and admire. But now you’re writing about washed-up rock stars with attitudes, which are decidedly tougher characters for viewers to connect with. How much harder has the writing process been this time?

Well, it’s easier by virtue of the fact that it’s only a half-hour [laughs]. On almost every other episode of Rescue Me we had a fire or an emergency call of some kind that would involve stunts, and smoke, and flames, and fire trucks. In Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll, we have a musical element, so we have to get into the studio with several of the actors and real musicians and work through the music. Sometimes it’s serious music; sometimes it’s comedy. When we get in the studio with the real musicians who are our tech advisers, there is a huge gap in talent, ability, and knowledge. And that actually convinces the actors in a weird way, including myself, that we really are failed rock stars.

Why are there so many ampersands and no spaces in Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll ?

It was actually a mistake on the cover page of the initial pilot script. I didn’t really think twice about it. And a few months went by and we were going into production and the first marketing things came in and all the words were run together with the ampersands. And I said, “So you guys don’t want to separate the words?” And they were like, “No, we liked the way it was on the title page of the pilot.” And I was like, “I think that was a mistake.” So now it’s just our trademark for as long as we exist.

Boston has produced many great comedians, including your Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll co-star Robert Kelly. Yet the comedy scene here is consistently referred to as inferior to New York’s. What’s up with that?

I think it’s an absolute fallacy, and it always has been. You have to understand that there’s something about Boston comedy crowds—it’s a combination of knowledge and enthusiasm, but they’re also tough. They’re not just going to sit there. They can smell blood. They can smell fear. I always felt like it was trial by fire in the Boston clubs in the best possible way. It’s kind of like sports fans in Boston—they really know what they’re watching.

So was Boston tougher on you as a young comedian than New York?

When I went to New York, I didn’t think it was tough at all. As a matter of fact, there was always a sense of murderers’ row on any night in Boston—you might be following Lenny Clarke, Steve Sweeney, Steven Wright. Every one of them could just kill. In New York, I could see two, three, four mediocre guys, and then Jon Stewart, and then a mediocre guy. You know what I mean? When I have my friends from New York come to Boston for Comics Come Home, they’re always afraid of following certain Boston comedians.

Is it true that you lived in the same building as Steven Tyler when you were a student at Emerson College in the late 1970s?

No. This is the story, and this isn’t talking out of school because Steven knows this. There’s a place called the Pour House across the street from the Prudential Center on Boylston. Back in my day, when that end of Boylston Street was pretty ragtag, that place was called the Honey Lounge, and the building above it had something like 10 apartments, and they were really cheap and they were pretty small, but who gave a fuck? I first moved in there when I was going to Emerson; it was me, Steven Wright, and a couple of other buddies. And we came to discover that there was a designer chick who lived on the first floor—I think her name was Angela—and she was dating Steven Tyler.

So was he around a lot?

The first time I met Steven Tyler was coming home from the Rat one night at like 3 o’clock in the morning. And when I opened the front door of my building to walk up the first flight of steps, I heard this guy screaming and ranting and punching and kicking something. So I turned the corner and it was Steven Tyler in full Steven Tyler getup and he was trying to knock this door down. He was screaming, “Angela, open this fucking door.” So I kind of snuck by him, and he looked at me and said, “Hey, man, do you know if Angela is home?” [Laughs.] And I go, “I don’t know, man, she’s not answering the door right now, I guess she’s not home.” He dated her for another year or two off and on, so that’s how I first met Steven Tyler. I was 19 or 20 years old and he was a gigantic fucking rock star. We were paying nothing to live in this shithole and sometimes you walked in and there was Steven Tyler.