Chaos, Order, Repetition: How Artist Amy Stacey Curtis Brings Abandoned Mills to Life

Still from Amy Stacey Curtis’s ‘How to Clean a Mill Floor’ via YouTube

Artist Amy Stacey Curtis filled a glass vial with exactly 562,437 grains of sand. Curtis knew how many grains were inside the vial because, over the course of 15 months, working for up to three hours each day, she counted each grain, quietly murmuring the numbers to herself. She carried that vial to an empty Maine mill—a space that she’d meticulously cleaned herself, scrubbing the floor on her hands and knees—and placed it on a long wooden rack containing 719 other vials, all empty. But the work was not yet complete. When her 2014 exhibition, “Matter” opened, she asked each visitor to pour the sand in each tube very carefully into the next one until, after 719 pours, all of the sand had reached the final vial. The piece can only be finished when Curtis recounts her small sand pile, measuring what was lost in the spills.

It’s all part of a deep art project nearly two decades in the making—and one that’s coming to an end this fall with “Memory,” a six-week-long exhibition in Lewiston, Maine. The project began in 1998, when Curtis resolved to produce a series of nine shows over the course of 18 years—her solo-biennials. Each show would be staged in a different abandoned mill in Maine, where Curtis has lived most of her life. Each would feature large-scale works devoted to such broad themes as “Light,” “Movement,” or “Change.” To carry out her plan, she broke down the years 1998 to 2016 into nine 24-month chunks. In each chunk, she would spend five months conceptualizing a show, 13 months working on artwork pre-production, and 10 weeks readying the mill and assembling the installations; once the show is over, she allots herself two months for recuperating. Then, armed with her plan, she stepped into her studio, bearing paintbrushes, bandsaws, knives, a laptop, a video camera—everything it took to bring her vision to life. She exhibited her first solo-biennial, “Experience,” in 2000 at the Bates Mill complex in Lewiston. Curtis, now 46, has returned there for her final one.

To prepare for “Memory,” which runs through October 28, she’d been working on a strict, self-enforced schedule—roughly 70 hours a week. Elegantly constructed with the aid of some 100 volunteer laborers, “Memory” takes over an entire floor of the Bates Mill with nine interactive installations exploring the human capacity to remember. One will feature nine tape recorders, each resting on a white pedestal and each bearing a recording of Curtis reading a nine-word sentence. Participants will listen, then press “record,” and repeat the sentence to the best of their ability. Another piece involves 900 blank cubes racked on slotted shelves, one per slot, each cube set atop a number. Each participant will remove a cube from a shelf, then try to remember the associated number beneath it before reracking the cube in a second numbered, slotted shelf roughly an hour later.

As Curtis sees it, a theme that unites her shows is “chaos, order, and repetition”—a conceptual trinity that “resonates physically, emotionally, and spiritually within and around all of us,” she writes. Think of the neatly counted sand, the incipient chaos inherent in a fallible participants trying to pour it into skinny vials, then the cool repetition of Curtis counting the sand again. In practice, her art blurs boundaries between artist and onlooker. She enlists audiences to deface perfect cubes of clay she’s sculpted, stain beakers of carefully measured volumes of water with eyedropperfuls of ink, and dismantle wooden structures—all to exact specifications. Even the industrial setting of each show gives voice to her themes: “The machines of the mill always worked together—order,” she says. “Then they spooled off in slightly different directions—chaos—before the whole thing repeated.”

Curtis has spent much of her life fascinated by the relationship between chaos and order. It started in 1995, three years before she set out on her biennial project, after reading James Gleick’s Chaos: Making a New Science. She was captivated by the book’s description of how researchers had discovered patterns in seemingly random natural phenomena—jagged forks of lightning, clusters of stars, branches of blood vessels. This revelation was a breakthrough for Curtis: “I was ‘hooked,’ fascinated that two historical opposites…had been found—through mathematics and science,” she writes. “Chaos should be seen as a ‘starting point’ in one’s personal search for a ‘new order.’”

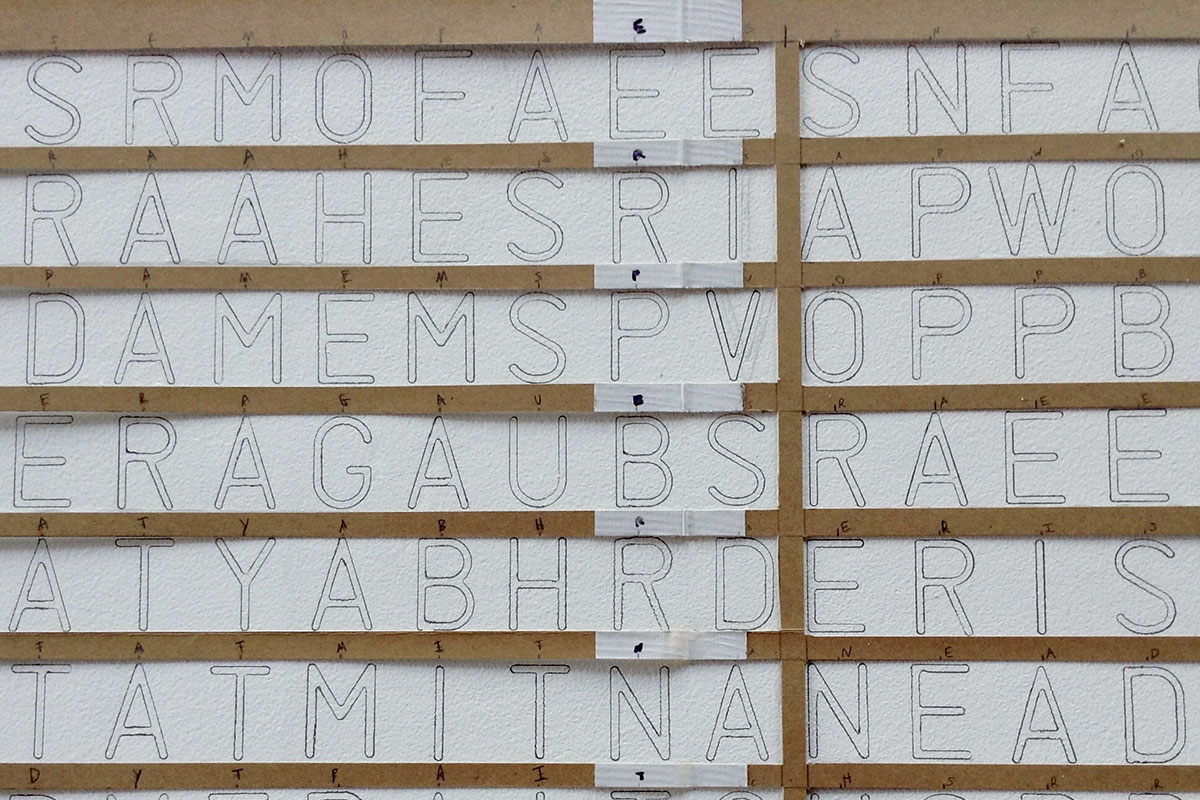

Process shot for undoing II, an installation featured in Amy Stacey Curtis’s ‘Memory’ / Image courtesy of the artist

On a cold gray morning, I visited Curtis at her home in the sticks of Lyman, Maine. The place is in a way a fortress: When she’s not working at University of Maine at Orono, where she teaches a class on professional development for artists, she’s most likely working here in her studio. After I arrived, Curtis offered—rather formally—to give me a tour. She showed me the basement, where she still has over 8,118 identically sized aluminum cans she collected, for her biennials “Change” (2004) and “Light” (2008). Each can is inlaid with a multicolored sheet of paper that seems to vary its color as the viewer observes it from different angles. She showed me vast piles of lumber she’ll use to stage her next show, as well as some drawings she was selling. She remarked that in her last home, an apartment, art supplies took up 75 percent of the square footage: “We had box mountains lining our walls and little paths going from room to room.” Her husband, Bill, wandered by in a Patriots hat, silently nodding that the box story was so, before vanishing upstairs.

“He’s very shy,” Curtis said, dotingly.

Eventually, I asked her about the significance of the number nine, which appears everywhere in her work. She explained that at her shows she often aims to have audience members experience repetition by, for instance, inserting pegs into a table drilled with holes. “Nine times conveys repetition without asking too much of people,” she said.

That’s it?

Well, there’s also nine Supreme Court justices, nine circles of heaven and hell in Dante’s Divine Comedy, nine muses in Greek mythology, nine elements in Hindu philosophy…

She was chummy, but also slightly impatient. She had not bargained for chit-chat, and I was there, ostensibly, to work. Because Curtis’s work is so large-scale, she has always been reliant on volunteer workers—interns, college students, art mavens, and also of course her husband. In 2014, Bill, a structural engineer, put in 28 volunteer days, installing handrails in the mill, and repairing stairs, replacing floorboards, and building supports to fortify eight weary columns.

My task: was to label the shelves that would hold 900 wooden cubes for the “Memory” exhibit. We worked side by side, as Curtis painted shelves. “G,” I pencilled into soft wood, “G, G, G, G, G, G, G, G.” I found the whole endeavor excruciating, exquisite in its boringness. But Curtis savors repetitive work. “It’s meditative,” she told me. “When I was counting that sand, the work was comforting. I always looked forward to it.”

As we worked, she started to tell me more of her story.

On December 7, 1977—she remembers the date precisely—Curtis’s life changed. The man she called her father—the man who married her mother and adopted Curtis when she was two—gathered her and her three younger brothers around the telephone. Then he called their mother: “If you don’t come for the children right now, I’m going to kill us all,” he told her.

He dressed Curtis and her brothers in snow clothes. Then, methodically, he led the children out onto the porch of their Stoneham apartment. They clasped hands and waited. Inside the apartment, he pulled down the shades and shot himself. Their mother rushed home to discover his body lying next to the bed. “She was never the same after that,” Curtis says.

Home was not a safe place. Curtis’s mother started dating again. One boyfriend often babysat. He “told our mother that I was beautiful,” Curtis would later write. One time, she recalls, “he pinned me against a wall” and rubbed himself against her. Her mother grew increasingly prone to violent rages. “I never knew what mood my mother was going to be in,” she remembers. “I did whatever I could do to minimize her rage. I cooked dinner. I cleaned. I tried to keep the house perfect. I was constantly planning; it was a way to survive.”

Curtis’s mother had a what she describes as a “breakdown” in 1979; after that, she started to take her children roller skating on weekends. For Curtis, it was a way out of the house, a reprieve from her mother’s rages, and also an entree into a zen-like calm she’d never known. She practiced four hours each weekday, whirling in tight circles hundreds of times in succession. When she was 11, she began roller skating competitively, traveling to rinks all over New England.

Later, she found nirvana in math. She was a star math student at Massabesic High School, in Maine—the smart aleck who sat in the front row in math class, waving her hand in the air.

It was in a calculus class that she first met Bill. Whenever the teacher told a joke, she broke into a loud, braying laughter and then turned to share her mirth with Bill, who cowered in the back row, blushing in agony over her public flirtation. He never flirted back, but—perhaps drawn to his quiet steadiness—Curtis was undeterred. Late in senior year, she called him and asked him out to dinner and a movie (Hellraiser was her film of choice, followed by McDonald’s). Within a few years, she asked him to marry her. “I didn’t wait for Bill to ask,” she later wrote on her blog, “as I had a plan”: a life in art.

In her senior year of high school, she had attended a weekend student retreat at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Deer Isle, Maine. “Completely supported and inspired, it was there that I chose to become a visual artist,” she writes. After graduation, she and Bill both enrolled in the University of Maine at Orono: he as an engineer, and she as double-major in studio art and advertising.

But even as Curtis built a stable life for herself, the tumult spun on. In 1994, her mother found a lover on the Internet, then fled her fifth husband, as well as Curtis’s beloved youngest brother, still in high school. She moved to California and changed her name, hiding her tracks so thoroughly that today no one in her extended family even knows if she is alive. “This happened,” Curtis told me, “before I’d forgiven her.”

In 1998, Curtis began pursuing a masters in Art and Psychology at Vermont College, and her studies there compelled her to write a book, Women, Trauma & Visual Expression. In this survey of trauma survivors and their art, she considered the work of nine female artists: four historically significant artists (including Frida Kahlo and Käthe Kollwitz), four contemporaries who had volunteered to share their personal histories, and the author herself. In those pages, Curtis considered her own early paintings, which often featured cells or repeated objects. “I began to recognize,” she wrote, that each cell could “represent a different component of my trauma. … I was separating each emotion, each sensation, each instinct, each perception, each moment—’breaking down’ my trauma into more and more pieces … toward less overwhelming feelings and sensations, towards healing.”

After each biennial, Curtis has experienced what she calls a “postpartum depression.” After 2012, she sunk into a depression that lasted 16 months. At a counselor’s recommendation, Curtis decided to undergo Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, a form of psychotherapy designed to help people heal from trauma. “EMDR is the most difficult personal work I’ve done; but it’s working,” she writes.

Getting ready for her final show has not been easy. In early 2016, Curtis was hospitalized with ischemic colitis. She was unable to work for six weeks, throwing her schedule off. “I was forced to do 17 weeks of work in 11 weeks,” she told me recently. She also reflected back on the epic ambition of the solo-biennials: “Maybe I set out to do an 18-year art project because I wasn’t ready to deal with other things,” she says. When she’s all done with her ninth and final show, Curtis has pondered going on a major road trip. It might be across the U.S. in a camper with Bill, but she’s not sure. “Maybe it’s best,” she said, “if this time my plan is to have no plan.”

In the workshop, as Curtis told me about her life, her tone was cool, as though she was talking about someone else. She spoke carefully, attentive to numbers and dates. There’s a reserve about Curtis, and also about her work. It’s minimalist, and it’s presented, always, with sleek grace, the backgrounds and pedestals resplendent white, the lines clean and unwavering. As Jessica May, the chief curator at the Portland Museum of Art, puts it, “She really controls the message.” But for all its formality, there is nothing cold or distant about it. There is immense heart in her work—even in her insistence on recounting the sand.

“Couldn’t you get the assistants to do the counting?” I asked.

“No,” Curtis said, “that would compromise the integrity. If I count the sand myself, it makes the piece stronger. People connect to it more.”

Curtis’s goal is to make that connection simple and direct. There are no polysyllabic artist’s statements at her shows. Rather, she asks viewers to cast about in the muck of the subconscious for meaning. “I want people to see what’s going on in their own lives,” she said. “It’s a blank slate I’m giving you.”

Often Curtis’s audience is deeply stirred. Once, when she asked each audience member to leave a personal possession atop a white pedestal, one person without explanation deposited a wedding ring. After another show, a guest told Curtis that seeing the installations helped her figure out how to communicate with her disabled son. Curator Jessica May calls Curtis’s work “sublime.” “It’s simple,” May says, “but it has a longstanding effect. You are aware, looking at one of her pieces, of all the conscientious labor that went into it, and the rallying of the entire set of resources she has at her disposal—her community, her friendships, her time, and every bit of care that she has. You wouldn’t think that watching a nine-second video of Amy Stacey Curtis taking a very slow walk would make you feel like you’re going to cry, but it does.”

My own inclination was to look for links to Curtis’s traumatic past. But of course her work is not about trauma in the way that, say, the haunted, suicidal poems of Sylvia Plath are. It is instead informed by trauma. It contains trauma, and it does it so serenely that at times I thought of the writer James Joyce, who once said, “The artist, like the God of the creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails.”

I wanted one more peek behind the curtain at Curtis’s workshop, so I went back to Lyman again, this time with my friend Rebecca, an artist and the person who’d introduced me to Curtis. When we arrived, after a 90-minute drive, at once I sensed a gate clanging shut. Curtis said she had allotted only an hour for us. She was friendly, but but so firm that I sensed that her agenda for this particular morning had been etched in stone several years earlier.

Soon, though, there was an almost oceanic opening, as Curtis immersed us in her artistic process. For Memory, she is making a video that will see 99 people in her life counting from 1 to 100. She wanted to film each of us counting, so she stepped outside, where Bill was weed-whacking the lawn, and gently asked him to turn off the engine. Then she led us into her studio and lay down on the rug wearing a hoodie and flapped ski hat. She started with Rebecca, carefully clasping her ankle and giving us explicit instruction. “Try to be still,” she said. “Have a resting face. I will be squeezing your ankle 100 times.”

Rebecca counted. Curtis wore earbuds as she lay there, listening to a metronomic pulse on her iPod. Her eyes were closed. The lights in the office were dimmed, and the moment felt sacrosanct. The numbers were an incantation, a promise, a prayer. I was aware of Curtis’s deep focus, and of the devotion she brought to this simple project, and in time I too closed my eyes and floated along in her bliss.