Lights! Camera! Newton?

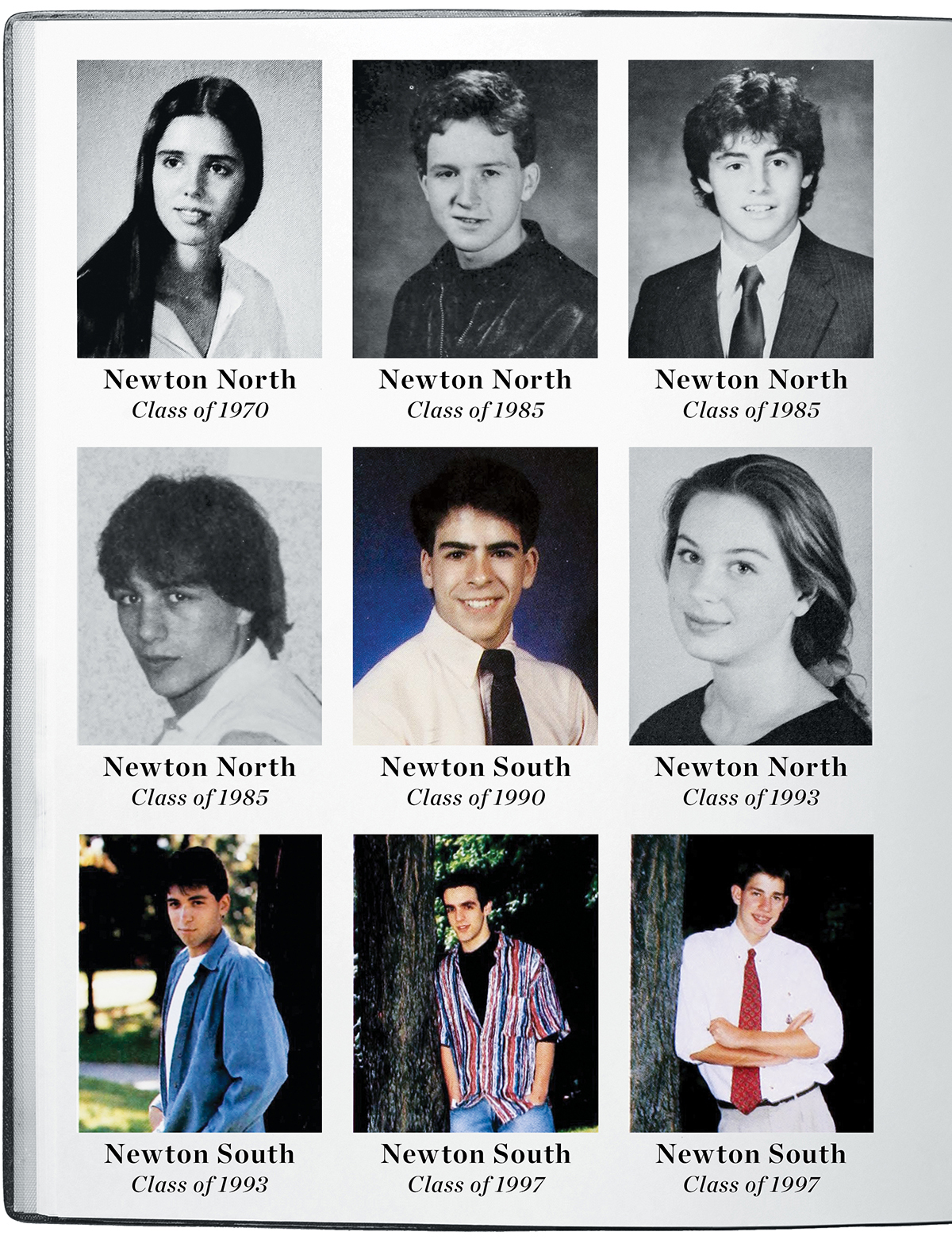

Click to view larger. / Before Photos Courtesy of Newton Public Library, Current by Trevor Reid (C.K.), WireImage

In one of the most talked-about bits from last year’s Emmys, comedian Jimmy Kimmel approached the mike to present the award for outstanding lead actor in a comedy series. Turning the envelope over in his hands, he joked that, really, no one would ever know if he announced the wrong name. “I can give the Emmy to whoever I want,” he teased the audience. “If the card says Louis C.K. and I say the Emmy goes to Matt LeBlanc, what are they going to do, stop the show? Are Ernst & Young going to leap on stage and wrestle the Emmy away from Joey Tribbiani? I don’t think so.”

Kimmel opened the envelope. Then he produced a pair of scissors, cut out the name of the winner, and stuffed it in his mouth.

Of the category’s seven nominees, the two men at the center of Kimmel’s bit, it so happens, hail from Newton. In fact, they’re both graduates of the same Newton North High School class of 1985. Back then, C.K. and LeBlanc knew each other, though they weren’t necessarily friends. C.K.—Louis Székely at the time—admittedly was “dropping acid” and breaking into cars. LeBlanc was a budding carpenter at the voc-tech who built and installed an entire kitchen for his senior class project. But they had one thing in common: They’d both been exposed to a culture that saw the arts as a legitimate and worthwhile pursuit. Boston was just over the horizon, a constant reminder of the reachable potential of something bigger; of a future far beyond Newton.

C.K. was 17 and manning the front desk at a video store when he heard about open-mike night at Stitches, a comedy club located at the time in the front room of the Paradise on Comm. Ave. He went, he bombed, but he kept going back. By the third try, he got some laughs, and that’s all the encouragement he needed. Around the same time, LeBlanc was working on a framing crew when he told his mom he was quitting and heading to New York. As LeBlanc later told Conan O’Brien, “She said, ‘Oh, Matthew, what do you know about acting?’” Turns out he knew at least a little. He landed a TV spot for Heinz ketchup, was able to make ends meet, and eventually commanded $1 million an episode for Friends.

“What does your mom say now?” O’Brien asked.

“Thanks for the Mercedes,” LeBlanc replied.

Though neither C.K. (who has an estimated net worth of $25 million) nor LeBlanc won Kimmel’s Emmy that night, it wasn’t the first time the hometown heroes had battled head to head at an awards show. Nor was it the first time two Newton natives had shared the spotlight. For nine seasons on NBC, actor John Krasinski and actor/ writer B.J. Novak—former Little League teammates and members of the Newton South High School class of 1997—starred on the Emmy- and Golden Globe Award–nominated TV show The Office. This was around the same time Newton native John Slattery was playing Mad Men’s louche-living Roger Sterling opposite fellow Newtonian Robert Morse as co-agency head Bert Cooper.

And there are others, lots of others, from comedian and sports commentator Joe Rogan; actor James Remar, of Dexter and Sex and the City; and Tony Award–winning film and stage director Julie Taymor (The Lion King), to Quantico actress Priyanka Chopra; Girls fan favorite Alex Karpovsky; and horror film director and producer Eli Roth (Grindhouse), who spent weekends in his parents’ basement making gory films with his friends from Newton South. Ben Kurland, part of the Oscar-winning cast of The Artist, began acting in first grade at the Fessenden School, following in the footsteps of Christopher Lloyd, a Fessenden alum whose acting debut was in a school play titled Submarine. Meanwhile, last season the hit Amazon show Transparent cast Hari Nef, Newton South class of ’11, who followed up the role with a part in the indie short Crush, opposite…Alex Karpovsky.

All of which might make more sense if we were talking about New York or L.A., or even Brooklyn or Beverly Hills. But Newton?

Newton’s Hollywood connection goes back nearly a century. Bette Davis, one of the city’s earliest claims to fame, spent a few high school years there in the 1920s. Next was Jack Lemmon, who attended Ward Elementary School until his parents sent him to private school in Brookline. During a 1988 speech while accepting a lifetime achievement award from the American Film Institute, Lemmon recalled his earliest years, saying that by the time he was eight or nine, all he wanted was to be an actor: “I acted in school plays, I acted at the drop of a hat, I’d act between classes.” Performing, he once said, gave him a feeling of acceptance.

Since then, Newton’s cast list has grown exponentially, thanks to a confluence of influential and invested educators and a deep-seated, community-wide interest in the performing arts. Morse, an actor with 70 credits, graduated in 1950 from Newton High School, where he’s said longtime music teacher Henry Lasker helped him find his artistic inspiration. Well known for creating an operatic version of “Jack and the Beanstalk,” Lasker was chairman of the Newton High School music department and a tireless advocate for the arts in schools, most notably incorporating music composition into music curriculum before it became a common practice. “He was an institution,” says Connie Kantar, former president and general manager of the Newton Symphony Orchestra, which Lasker founded in 1965. (She’s also, it so happens, the sister of Paul Michael Glaser, known as Starsky from the 1970s cop show Starsky and Hutch.)

Following Lasker’s death in 1976, Newton North renamed its auditorium in his honor. Today the Dore & Whittier–designed performing arts center is one of the most talked-about features of the six-year-old, $197 million, new Newton North. It stands as an important reminder that in Newton the arts are, as the former director of the theater program at Newton South, Jim Honeyman, says, “an integral part of the development of the whole person—mind, body, spirit, heart—definitely not a frill.”

During Lasker’s tenure, from the 1940s through the mid-1970s, Newton emerged as a city that appealed to parents who worked in or were interested in the arts—and who valued arts education in their children’s schools. Julie Taymor was raised in one of these families. Her parents loved the theater and took her to shows, which led to her putting on plays in the backyard with her older sister. By the time Taymor was nine, she was taking the T from Newton to downtown Boston every day after school for two to four hours of rehearsals at the Boston Children’s Theater. “It’s really how you’re brought up, who your parents are,” Taymor says. “If you have teachers who are inspiring in the arts, you’re going to get kids who are into it.”

In 1973, whether they knew it or not, many of Newton’s future stars got a major boost. A Brooklyn native named Linda Plaut, who’d grown up “with music all around,” moved to Newton with her two young children. After taking a job as the director of Arts in the Parks in 1975, Plaut says she “realized that there was very little for families to do during school vacations and weekends. That’s what inspired me to begin programming vacation and summer events for families.” Nearly 40 years later, Newton’s Office for Cultural Affairs, with Plaut at the helm, oversees a full calendar of programs and events that include Newton Open Studios, the children’s theater Newton Youth Players, and the annual Festival of the Arts—100 separate events over a three-month period. “Whether or not you take part in that aspect of life in Newton,” Plaut says, “it’s something that everyone can feel.”

By the time Novak and Krasinski came around, everyone did. Even though U.S. public schools as a whole have cut back on arts education in recent years, Newton’s programs receive plenty of support from parents and the community, through fundraisers, individual donations, and ticket sales from school shows.

Both high schools put on multiple productions a year—auditions for which are highly competitive—and offer arts classes in a variety of fields, from acting and playwriting to costume and set design, taught by multiple faculty members. While many high schools toy around with productions of Our Town or Oklahoma, Newton puts on provocative, complex shows including Avenue Q and Ruthless. Aside from a part as Daddy Warbucks in a sixth-grade production of Annie, Krasinski’s stage debut was when his pal Novak convinced him to take part in the annual parody show during their senior year. “I will give B.J. a ton of credit for that,” Krasinski says. “I loved my experience so much with that senior show—it sort of changed my trajectory. For me, the most fun and the most inspiring and the reason why I wanted to be an actor was because of the community.”