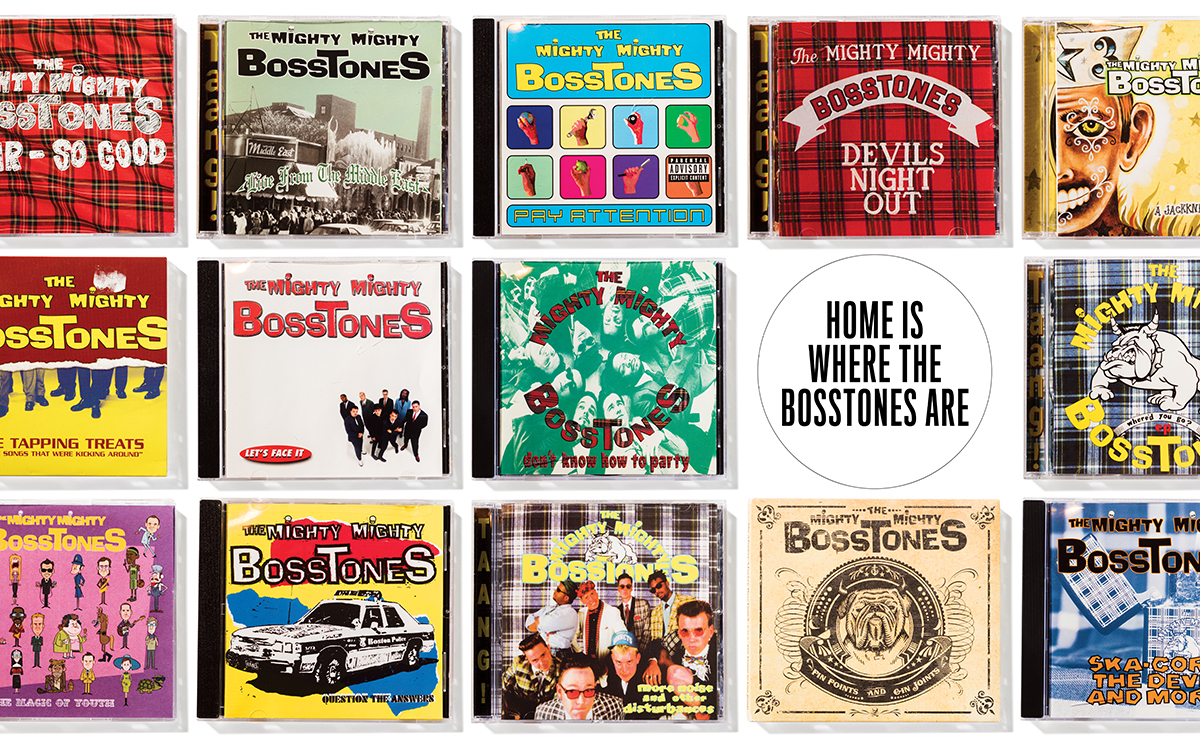

Home Is Where the Bosstones Are

Photograph by Jenna Skutnik

I had dreaded the day, and then it came. Arrayed along the wall of my cramped home office in Brooklyn were about 1,200 CDs. After 25 years of obsessive acquisition and artful pruning, I had been left with what I considered to be the absolute essentials, albums that did what great albums do: slake a thirst you didn’t know you had, and save you from the unimaginable fate of having lived your life without ever hearing them, which in retrospect could hardy be called living at all.

And they were all going in the garbage.

All right, not the garbage. But they were going. I had a kid on the way and was moving to a new apartment. I needed space, and since I had largely switched to digital music, I had mostly stopped playing CDs anyway. The time had come. So I stacked it all into grocery bags, and out the door it went. Most CDs were destined for the Salvation Army, some were sold off for pennies on the dollar to the sorts of niche music stores that now attract only vaguely dusty-looking, misshapen, unaccompanied middle-aged men, and the mangled ones went in the garbage. I expected the purge to be agony, which is why I had put it off for so long. But when it was over I felt fine. Unburdened. You could even say that when they all were gone, I was feeling good.

Which is a line from a Mighty Mighty Bosstones song, by the way. “Awfully Quiet.” Which comes from a 1992 release titled More Noise and Other Disturbances. Which—okay, I lied—I didn’t get rid of that one. It was the first album I ever loved. Nor did I get rid of Don’t Know How to Party; Ska-Core, the Devil and More; or even the EP with the questionable cover of Metallica’s “Enter Sandman.” In fact, I didn’t get rid of any of my Bosstones CDs. I couldn’t even bear the thought of it.

Hoping to understand the hold this band has on me, I reached out to Dicky Barrett, the Bosstones’ frontman, who’s currently working for Jimmy Kimmel. I started telling him about the purge. Halfway through, though, he cut me off. “Take those CDs and throw them in the trash,” he said. “Walk away from them. Don’t carry them through life. Live in the modern world.”

But as I sat in my old office, staring at these discs stacked neatly on an empty shelf, I realized something: I will not walk away from them. I will carry these goddamn things with me for the rest of my life.

But then I began to wonder, Why?

And the answer came to me:

Boston, Massachusetts.

The Bosstones formed in 1984, when guitarist Nate Albert, bassist Joe Gittleman, and skanker Ben Carr, high school friends from Cambridge, recruited Barrett, a relative veteran of the local hardcore scene, to play in their band. Barrett had come to Boston immediately upon graduating from high school in Norwood (he actually packed his bags at his graduation party), and moved into the punk-rock flat on Queensbury Street since immortalized in the 1994 song “Toxic Toast” (“Just across from Wayne’s Junk Store, three floors up then straight ahead / If someone thought to lock the door, use the fire escape instead”). Barrett took to Albert and Gittleman immediately. He recalls that Gittleman’s “hippie mother said a psychic told her we were brothers in another life.”

The four kids, who did become close like brothers, added four more band members: three horns and a drummer. They pioneered a sound blending ska and hardcore—“ska-core”—and called themselves the Bosstones. They augmented that after someone at the late, great Boston punk club the Rat put “Mighty Mighty” on the chalkboard advertising a gig. By 2003, the band had released seven studio albums, two EPs, and a live record. They traveled the world. They were featured in an ad for Chuck Taylors. They had an underground hit, “Someday I Suppose,” which got them a cameo in the film Clueless. They peaked commercially in 1997 with Let’s Face It, which featured the monster hit “The Impression That I Get.” It went platinum, selling some 3 million copies globally. Granted, that was a different time, before the implosion of the music business, but it’s worth noting that Let’s Face It has so far sold more copies than Beyoncé’s Lemonade.

Then they slid, stalled, ran out of inspiration. They were (unfairly) lumped in with a thousand carbon-copy 1990s pop-ska bands past their sell-by, and derided and dismissed. They drifted apart from one another, and I from them.

But all that came later.

I was a portly, sports-obsessed, wiffle-headed, shelltoe-wearing 14-year-old when I walked onto the back porch of my childhood home in Quincy in the summer of 1992 and heard “Where’d You Go?” on WFNX. It was a clear, sunny day that I now remember more vividly than I remember whatever happened 20 minutes ago. I had never heard anything like that song. The syncopation, the horns, the bass, Dicky Barrett’s brutal Boston accent. I wasn’t a big music fan then. That might be overstating it, actually. According to my eighth-grade yearbook, my favorite song was “Dope!” by Bell Biv DeVoe, for Chrissakes.

But after I heard that Bosstones song, I was done for. The course was now charted, and I was doomed to spend the rest of my life, and much of my disposable income, trying with varying degrees of success to re-create that sensation. I went to Newbury Comics that very day and bought More Noise and Other Disturbances, and I played it so many times I’m surprised it didn’t evaporate under the laser in my CD player.

That album was pure bedlam—pissed off, hilarious, giddy, catchy, aggressive, socially conscious at points and drunk and crazy at others. The musicianship was stellar (the Bosstones have never gotten their due for how good they are), and Dicky Barrett came off as one of those rare performers who is both a terrible singer and a world-class frontman. But the thing that got me was More Noise’s profound Boston-centricity. Not only did Barrett sing with a Boston accent—a rarity even in Boston music—but the album was also loaded with local references: riding the T, legendary newscaster Jack Williams. This has been the case on every Bosstones release since, with varying degrees of subtlety, which causes the local fans to parse them with Talmudic seriousness.

Still, no single track on More Noise contained a purer Bostonian distillate than “They Came to Boston.”

They came to Boston on their vacation

They came, they saw, they annoyed me

They saw it all—what? Faneuil Hall

It’s best if they just avoid me

Rented a car to see the sights

But they found the Hub confusing

Looked for the Swan Boats in Mattapan

Well, I find that real amusing

I was here before they came

I’ll be here long after

Don’t want to share, but it seems clear

That I’m gonna have to

The song, which goes on to bitch about college students (“jam my bars and subway cars…when the hell’s graduation?”), works on a few levels. It’s a great tune, well played, with descending chords in the chorus that create a mad whorl suggesting, fittingly, it turned out, a drain. It captures something universal about the Boston experience—how exhausting it can be to live in a town of transients—that was almost orgasmically gratifying to hear as a kid.

But most important, the song speaks to a mindset that I’ve always considered quintessentially Bostonian, one that is often overlooked. Not our old and widely lampooned wariness of outsiders. Something more interesting. It’s this strange ability to feel both young and old at once, to be full of youth and reckless exuberance, but also react to everything like a sentimental 80-year-old crank rotting into a porch in Hyde Park. It’s a dichotomy that runs throughout all of the Bosstones’ work. Take these verses from a song on their first full-length record, Devil’s Night Out:

I used to talk to cab drivers, now I just don’t bother

I’d empty out my pockets if someone asked me for a quarter

There was a time I’d give the time

To the old, the weak, and the weird

I just don’t know why this is so but I’ve never been so scared

Am I getting older?

Are things getting harder?

I used to never cry when I would think about my father

That’s not an uncommon sentiment for a middle-aged man, coming off a divorce maybe, or a layoff. But Dicky Barrett was 24 years old when that album came out. To further complicate things, on that same album, he remarks of his youth, “I hope it never ends.”