Bob Dylan’s Lowell Show Is More Than a Concert: It’s a Requiem for Jack Kerouac

The singer was hugely influenced by the writing of the Lowell native.

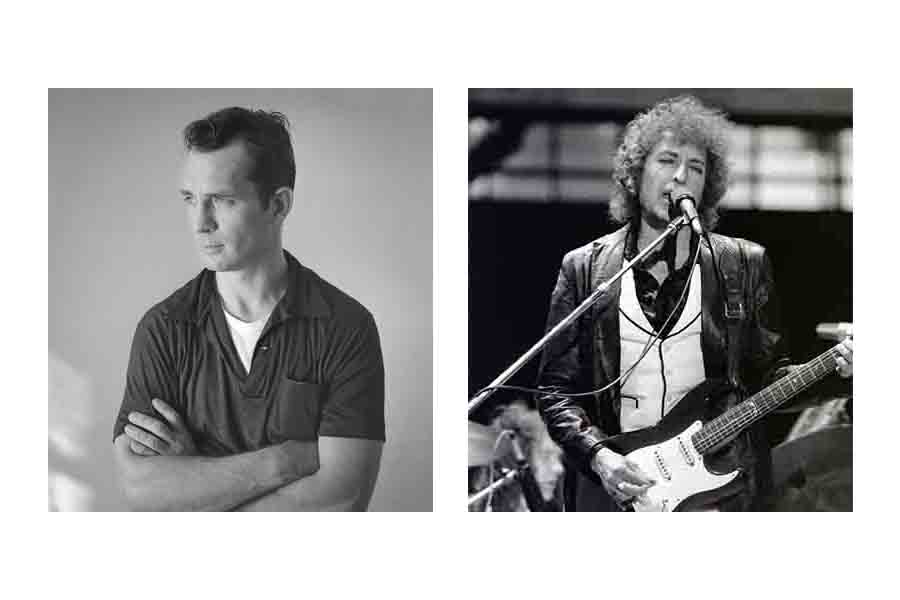

Jack Kerouac photo by Tom Palumbo, Bob Dylan photo via Wikimedia

In the extended twilight of his career, Bob Dylan is playing a concert in Lowell on Tuesday night, and in so doing, paying tribute to his unseen sideman and collaborator, Jack Kerouac. When Dylan and his band arrive at the venue, their cortege will bookend a procession that occurred fifty years earlier. On October 24, 1969, limos filled with Jack Kerouac’s old football teammates and the few remaining Beat writers departed Archambault Funeral Home, following the hearse that carried Kerouac’s remains to Lowell’s Edson Cemetery. There, Kerouac, who was born and raised in Lowell, was interred beneath a simple plaque that read:

“Ti Jean”

John L. Kerouac

Mar. 12, 1922 – Oct. 21, 1969

— He Honored Life –

Six years after Kerouac’s death, in 1975, a then-34-year-old Bob Dylan visited Kerouac’s grave in the same windswept season of the year. Dylan was in town with his Rolling Thunder Revue, a kind of musical carnival that included musicians Joan Baez, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Mick Ronson, playwright Sam Shepherd, actress Ronnie Blakely, and Kerouac’s close friend and pallbearer, the poet Allen Ginsberg. Restless after years of relative seclusion, and already keen on outrunning his fame, Dylan chose gritty, blue collar Lowell because it was Kerouac’s hometown and his muse, and the young singer songwriter felt a strong kinship with the Beat writer. Dylan and Ginsberg went to Kerouac’s grave the day after the show, on November 3, 1975.

For Tuesday’s show, Bob Dylan and his band will perform at the Tsongas Center, hard by the University of Massachusetts Lowell. Older now, and with a different band, Dylan’s performance will provide a resounding encore for that long-ago concert, when 14,000 fans crammed into the university’s gymnasium to see the foremost lyricist of the era. That night in 1975, Dylan dedicated “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” to Kerouac, and closed the show with “This Land is Your Land,” joined on stage by Allen Ginsberg, Dylan’s mother Beatty Zimmerman, and other members of their traveling road show.

Dylan played a few more gigs in Lowell over the years, but Tuesday’s show will provide another meaning, another sort of farewell. By visiting Lowell this late in the game, Dylan will compose a requiem for Kerouac, who was one of his most significant influences—an older brother who left his modest hometown for New York years earlier, searching for enlightenment.

In the spring of 1947, Kerouac, then a young unknown writer, rode the 7th Avenue subway to the end of the line, stuck out his thumb, and began hitchhiking. His trip, and the novel that grew out of it, would change the course of American literature. His wanderings over the next several years, from New York to Chicago to Denver and back again, in freight trains, travel bureau cars, and buses; San Fran to Fresno; North Carolina to New Orleans; through Colorado, across the Texas plains, and down to Mexico City, would be immortalized in his 1957 masterpiece, On the Road, a book so important to Dylan and the evolution of his storytelling that he states it plainly on his website.

As artists, Kerouac and Dylan share a number of striking similarities. Foremost is each man’s dedication to his craft and indifference to the trappings of success. When Dylan was awarded the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature, he reacted as if he’d been named Man of the Year by the Minneapolis Elks Club, not bothering to show up for the ceremony, and skipping the chance to deliver his Nobel lecture a year later, which was instead read by the U.S. ambassador to Sweden. In much the same vein, in a pair of letters to the poet Gary Snyder in 1959, Kerouac complained about “how awful it is to be ‘famous’ (fame mouse) at least in America”, and that all the hoopla and hyperbole over his 1957 novel, On the Road, had left him “fat, dejected, ashamed, bored, pestered & shot.”

Despite the fact they never met, the relationship between Kerouac and Dylan illustrates the progression of the American story. Considering that the most original contributions to the story are jazz and the blues, it’s no surprise Dylan and Kerouac were both influenced by this tradition of American storytelling. But just as Dylan would a few years later, Kerouac moved beyond his early influences to something new. In an introduction to his 1960 novel Lonesome Traveler, Kerouac says he “read the life of Jack London at 18 and decided to also be an adventurer,” and that his influences included “Saroyan and Hemingway; later Wolfe.”

But in New York, the restless young scribbler discovered bebop jazz, and saxophonist Charlie Parker, in particular. Ginsberg noted in an interview that Kerouac “learned his line directly from Charlie Parker”, and Kerouac himself told Ted Berrigan of the Paris Review that he was like “a tenor man drawing a breath and blowing a phrase on his saxophone, till he runs out of breath, and when he does, his statement’s been made.” Parker even appears as a “character” in Kerouac’s The Subterraneans, demonstrating the importance of this American original to Kerouac’s development. In the book, Kerouac’s narrator, Leo Percepied, notes that Parker, during a nightclub performance, gazed “directly into my eye looking to search if really I was that great writer I thought myself to be.”

Kerouac described the visceral impact of Parker’s music in a March 19, 1957 letter to his editor Don Allen: “So I eschews ‘selectivity’ and follow free association of mind into limitless blow-on-subject seas of thought… with no discipline other than the story-line and the rhythm of rhetorical exhalation and expostulated statement, like a fist coming down ona table with each complete utterance, bang!”

Shortly after the harried novelist left New York, the young Dylan arrived, taking up Kerouac’s mantle as a kind of hoodlum saint, and banging on the same tables. In those days, Bob Dylan’s biggest inspirations were the Great American Songbook and the music of his idol, Woody Guthrie. Like Kerouac taking stock of Wolfe’s Asheville, North Carolina, and migrating the same preoccupations with home ground, blood, and tragedy north to Lowell, Dylan’s ragged vocals, idiosyncratic phrasing, and raucous harmonica took American folk music in a new direction.

After Kerouac’s death, Dylan reportedly told Ginsberg that he read Kerouac’s book of poetry, Mexico City Blues, in 1959 and it “blew (his) mind.” Dylan was hearing “his own American language” for the first time, learning from Kerouac what the writer had absorbed from Charlie Parker. Dylan responded to Kerouac as one musician to another, moving from the rigid confines of the old structures and tropes to new creative vistas—the startling juxtapositions of his reality grounded in the particulars of the every day.

In the cavalcade of rueful Americana that includes Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, Leadbelly, Langston Hughes, Faulkner, Steinbeck, Charlie Parker, and Willa Cather, among others, Dylan follows close on Kerouac’s heels. At his best, Kerouac was deep into improvising, noodling over the flow of his thoughts—combining all his influences and training and just starting to play—and Dylan took up this song and continued it, a haunting melody that floats through American culture to this day.

The Lowell sky is low and sodden, hanging over the city, fine lines of rain falling fast and silvery over the old mills and cobblestone streets. Zooming past Lowell High School where Kerouac was a star athlete and an exceptional student, I’m dodging cars and pedestrians on my mountain bike while listening to Dylan’s “Desolation Row.”

I read On the Road when I was 20-years-old. I was a college student, living in a tiny apartment above the Acadia movie theatre in Wolfille, Nova Scotia when I finished the book. Sometime after midnight I heard the wail of a freight train charging along the Bay of Fundy and had the most acute sensation of homesickness I’d ever felt. I was listening to Dylan’s “Blood on the Tracks” and Kerouac’s blue-collar voice was reinforced—hip, iconoclastic, with a brashness that contained notes of joy underscored by a lament. Because for all its exuberance, On the Road was a sad story and Kerouac a guy like me, a watcher, born in Lowell, two towns over from my home ground, Methuen. I’ve been looking for Kerouac in Lowell ever since.

Earlier I’d passed the old Lowell Sun building, where Kerouac worked briefly as a sportswriter, and cruised over to the Jack Kerouac Commemorative on Bridge Street. Composed of reddish brown granite tablets arranged in a circle, the stones were cut and polished in Minnesota, then sandblasted with passages from Kerouac’s books. A buddy of mine, local poet Paul Marion, who edited a collection of Kerouac’s early works, Atop an Underwood, was one of the driving forces behind the commemorative, which was dedicated in 1988.

Straddling my bike, I pause by a favorite passage from Kerouac’s The Scripture of the Golden Eternity:

When you’ve understood this scripture, throw it away. If you can’t understand this scripture, throw it away. I insist on your freedom.

I have to laugh thinking of Marion’s quixotic journey to restore Kerouac to his rightful place in local mythology. Among my favorite stories is the day in 1991 when Paul took budding movie star Johnny Depp on a tour of Kerouac’s haunts. They drank cognac at the home of the late John Sampas, Kerouac’s brother-in-law and estate manager, and looked through Kerouac’s old clothes, photographs, and notebooks. “I can’t believe I’m in Lowell,” Depp said. “This is like touching the robes of Christ.” Depp’s visit concluded with dinner at a restaurant that was originally Nicky’s Bar, owned by Kerouac’s other brother-in-law, Nick Sampas, where I’d been unceremoniously tossed out during my intemperate youth.

Now I’m highballing along Pawtucket Street in the misting rain. As I approach the Archambault Funeral Home, I ride onto the sidewalk. But there’s a college kid absorbed in his phone blocking the way, so I drop back off the curb. I can feel the pressure of traffic, and look to jump the curb again. My front tire catches the top edge and I’m flung to the pavement, landing hard and opening up cuts on my knee. My helmet crashes against the sidewalk, ringing my bell, and I roll into a sitting position.

The kid rushes over. “Are you okay?”

Hauling myself up, I say, “It knocked some sense into me.”

Flush with adrenaline and a bit dazed, I remount the bike in a state of satori, or Buddhist enlightenment. As I steer past the funeral home and take a ride through the Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes, where Kerouac’s mother, Gabrielle, would pray to the Virgin Mary, I’m listening to Dylan again and the most profound connection between Kerouac and Bob Dylan becomes clear.

In Lonesome Traveler, Kerouac riffs on “the smell of soured old shirts lingering above the cookpot steams as if they were making skidrow lumberjack stews out of San Francisco ancient Chinese mildewed laundries with poker games in the back among the barrels and the rats of the earthquake days…”

Partway through “Desolation Row,” a song poem that echoes the title of Kerouac’s novel, Desolation Angels, Dylan runs through the very same “breath sentences of the mind” the beat writer learned from Charlie Parker, paddling down the stream of consciousness in Kerouac’s wake:

And Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot

Fighting in the captain’s tower

While calypso singers laugh at them

And fisherman hold flowers

Between the windows of the sea

Where lovely mermaids flow

And nobody has to think too much about Desolation Row

By now, I’m cranking past St. Jean-Baptiste, where Kerouac’s funeral mass took place. Suddenly I realize where I’m going, where I’ve been headed all along. Soon thereafter, I roll beneath an iron gateway into Edson Cemetery on Gorham Street. The rain has subsided, and there’s not another living soul across the leaf-scattered plain.

Not long after I finished reading On the Road, I hitchhiked home for Christmas, and late one night drove over to Lowell with two of my college buddies, Bongo and Pitch. At Edson cemetery I parked my dad’s station wagon beside a huge oak tree, and we scrambled onto the roof, grabbed the lowest branches, and swung ourselves over the fence, bottles of beer clanking in our pockets. Bongo and Pitch and I stood around in our varsity jackets sipping beer, not saying very much. It was a pivotal moment in my life. After reading Kerouac’s novel and becoming enamored of its “innumerable riotous angelic particulars,” I said the hell with law school. I had no time for any of that, and a preoccupation with time and how to best make use of it runs straight through everything I’ve done since, fueling my career as a writer.

When Dylan and Ginsberg visited Kerouac’s grave in November 1975, the sky was framed by skeletal oak trees with dead leaves littering the ground. Ginsberg noted that the poet John Keats’ gravestone includes the epitaph, “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water.”

The two men stared down at Kerouac’s plaque. “What graves have you seen?” Ginsberg asked.

“Victor Hugo’s grave,” said Dylan.

Smiling for a moment, Ginsberg pointed to the ground. “So, is this what’s gonna happen to you?”

Dylan continued to look down, the brim of his cowboy hat shading his eyes. “No, I wanna be in an unmarked grave,” he said.

I lean my bike against a tree and walk over to Jack’s grave. As usual, there’s several items on the ground—coins, poems, a framed photograph or two, the stub of a half smoked joint. Standing there with no one around, I say a Hail Mary for my fellow Catholic, adding “Dear Mary, please say a prayer for Jack Kerouac and ask your Son to permit Jack into His Kingdom.”

The sky has turned gun-metal gray, with a chilly wind blowing from the east. I dig in my pack for an energy bar and drink some water, glancing up at the sky. It’s getting late for biking over the crowded rainy streets—as Dylan wrote, “It’s not dark yet/but it’s gettin’ there.” Rolling out through the gate, I switch on Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright” and it occurs to me that, when the 78-year-old troubadour ambles off stage Tuesday night, Jack Kerouac may have spoken in Lowell for the last time.