An Oral History of Wally’s Café

Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Dexter Gordon. All the greats came to Wally’s in the South End. Now, nearly 75 years after the birth of the legendary nightspot, the people who lived it retell the making of the city’s coolest and most important jazz club ever.

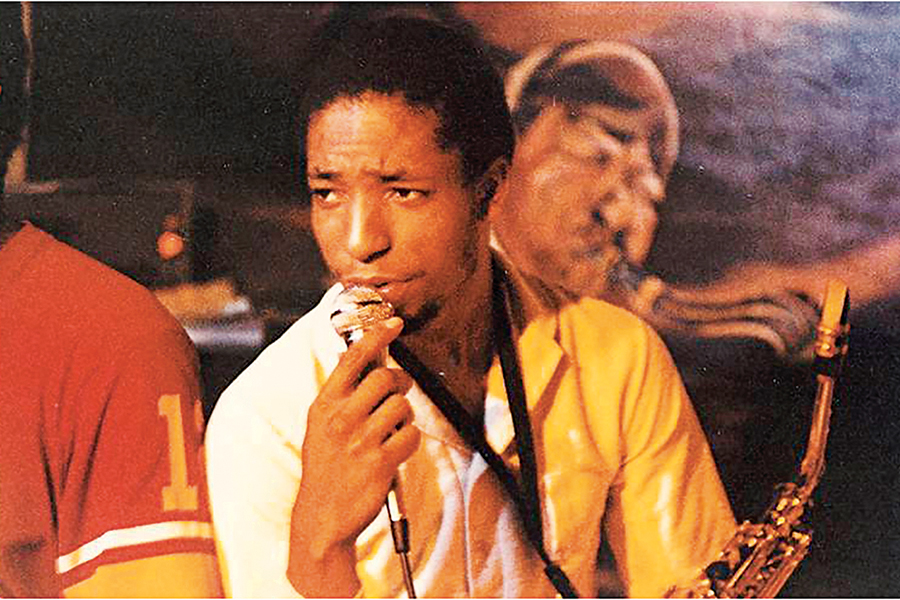

Legendary saxophone player Donald Harrison Jr., Berklee class of 1981, once performed four times a week at Wally’s; his nephew, five-time Grammy nominee Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah, also took the stage there later. / Photo courtesy of Wally’s Cafe

When Wally’s Paradise opened its doors in 1947, it wasn’t just serving up stiff drinks and smokin’ jazz to patrons—it was making history. After all, proprietor Joseph “Wally” Walcott was the first Black man in New England to own a nightclub, and the first to be granted a liquor license in the city of Boston. Over time, the venue became more than just a place to watch tomorrow’s Grammy-winning jazz sensations cut their teeth: It emerged as a hub for Black culture that has endured for decades.

As the club, now located across the street from the original location and known as Wally’s Café, enters its 75th year of existence, it does so with its doors closed to the public because of COVID-19 restrictions. Wally’s grandsons, who run the place today, say they’re committed to keeping their family business going—and an entire community is counting on them to make it happen.

Elynor Walcott Poindexter, owner of Wally’s and daughter of Joseph “Wally” Walcott: We’re at 427 Mass. Ave. now, but for years Wally’s was across the street, directly across, at 426 and 428. My mother and my father got that place together. I was a newborn. My father told me that they had me in a basket, and brought a brand-new box of salt and a brand-new broom. Those two items were blessings that they believed would lead to longevity. So I guess it paid off.

Richard Vacca, historian of Boston jazz: In 1947, when Wally’s opened, there were already two jazz clubs on that block, but both were owned by white guys. So I think it was really important from a neighborhood point of view, maybe from a pride point of view, that here was the first time that a nightclub in New England was owned and operated by a Black guy. This was finally a place where people could get together and relax without having to worry about admissions criteria or any of that kind of stuff. In other words, they could be served.

Matt Sonny Carrington, saxophonist: What Wally’s had that was different than the others was the space for a dance floor. It was a little more social because of being able to dance. So everybody came in there: Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Dexter Gordon.

Vacca: Until 1948 the Hi-Hat [a club across the street] was whites-only—the only Black people that were in the place before 1948 were serving the food, washing the dishes, and so forth. Wally’s attracted a crowd, and the guys who owned the Hi-Hat saw what was going on. So the next year they converted from being a whites-only dine-and-dance place to a jazz club with an open-door and colorblind-admissions policy. So I think that had a big effect on the neighborhood and in the community.

Matt Sonny Carrington: By the time I started playing there in the early 1950s, Columbus Avenue in the South End was the mecca for jazz. Because you didn’t just have Wally’s. Up another four or five doors, there was the Big M, which was called Morley’s. Across the street was the Hi-Hat, the Wigwam, and then there was Eddie’s. You had five clubs on that block. You can’t imagine that, can you? Five nightclubs that played jazz. It was unbelievable. So we had our own thing as a community. That strip was our strip; it was like a little New York City. No one went home before 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning.

Elynor Walcott Poindexter: I was always going to Wally’s after school when I was in elementary school, grammar school, and high school. My girlfriends and I, we would go by there, and my father would give us money to go get ice cream, and tell us, “Okay, keep it moving.” He wouldn’t let us linger. It was a drinking establishment. I came up in a structured house. And then when I got to be 21 my father told the bartender, “Okay, take her behind the bar and teach her how to tend bar.”

Matt Sonny Carrington: When I first started playing, I was playing drums, and I would go in and sit in as a young drummer, a teenager, so that was my first experience. Later on, when I had taken up the saxophone and got going a bit, I was able to get gigs. I started working every other weekend. Wally didn’t pay a lot of money, so guys would leave off a weekend or so to play another gig that paid more money, and I would take their place. I was glad to get whatever I could, just to get the experience to play with a band and have a jazz audience here in Boston.

Joseph “Wally” Walcott at the bar of the club he founded in 1947. / Photo by Jonathan Wiggs/The Boston Globe/Getty Images

Elynor Walcott Poindexter: The first time my father went out of town and left the club was after his manager passed away, and that’s how I got the reins of being a manager. My cousin also worked as a manager and he went back to Barbados. He was supposed to be gone for 21 days, but he didn’t come back and I ended up with his job. I think I was in my twenties.

Matt Sonny Carrington: When my daughter Terri was eight or nine years old, somewhere in that vicinity, I would bring her in there to get a chance to play with the musicians there.

Elynor Walcott Poindexter: Isn’t that sweet? When that little girl was eight years old, her father was bringing her into Wally’s and putting a telephone book on the drum seat. And he was standing up on the dance floor, at the microphone with his saxophone, and his little daughter was on the drums, learning how to play.

Terri Lyne Carrington, drummer and three-time Grammy-winning bandleader: I’ve been going to jazz clubs since I was five, probably. I can’t say that Wally’s was the first club I played in, but it was one of the first.

Elynor Walcott Poindexter: There was one event at Wally’s I will never forget because it was when musicians gave an award to honor my father.

Matt Sonny Carrington: I was president of the Boston Jazz Society at the time, and I gave him the award from the society for his contribution to jazz over the years.

Elynor Walcott Poindexter: The place was huge, mega big, and you couldn’t see the floor there were so many people. It was just loaded. We had these high-back booths, and people were sitting on top of the backs of the booths. There was a cigarette machine back then and they were sitting on top of the cigarette machine. There were just so many people, and I looked at that as quite a tribute to Wally’s and to my dad.

Matt Sonny Carrington: Everyone at the ceremony had been patrons of his establishment for years. It was a chance to give Wally his due while he still had the old place.

In 1978, the city took over Wally’s Paradise through eminent domain for a highway that ultimately was never built, forcing the Walcott family to find a new home for the club, which they reopened the following year.

Elynor Walcott Poindexter: I’m the one who convinced my father to move Wally’s across the street. He didn’t want to be there. He was looking for a bigger place. I took him across the street, and the building was abandoned. It was just him and me looking through the window of the abandoned building. He said, “In here, Ely? This little bitty place?” I said, “Yeah, ’cause when people come to Wally’s and they see that it’s closed, they’ll say, ‘Where’s Wally’s?’ and they’ll just turn their heads and they’ll see: ‘Oh, there it is.’” And I was right!

Greg Osby, saxophonist: I led bands at Wally’s in the early 1980s while I was a student at Berklee. The South End was the depths of hell at that time. It’s all restored now—repointed brick and redone brownstones and paved sidewalks—but at that time it was all broken glass, syringes, discarded alcohol bottles and beer cans, and the shadiest characters that you can imagine. And it was dark, a lot of streetlights out, and nobody wanted to go there except people who really wanted to play. It didn’t bother me one bit because I’m from St. Louis, so I don’t have to say any more. I was totally comfortable around shifty characters—hustlers and pimps and the underbelly of society. But a lot of people were just shaking in their boots, and they would never have gone to Wally’s. It would have been to their benefit to have braved the wilds.

Elynor Walcott Poindexter: One thing about Wally’s: There was this hodgepodge of different personalities, and there would always be something interesting going on. In a positive way—no dull moments, so to speak.

Osby: There was a cast of regulars that frequented the place. They were characters. You don’t really have that anymore, these kinds of places where the hard-core listeners actually saw Bird, Lou Donaldson, Cannonball Adderley, and Duke Ellington live. They openly criticized and chastised a lot of people. And a lot of people ran out of the club with their tail between their legs and didn’t come back until they had things worked out. Another fixture was the bartender Ducky. Man, she was brutal. Really rough around the edges, but a really sweet core. She would cuss like a sailor, and she was, like, unedited. I mean, she had no filter. She would say, “Listen! You come here, you stand up against the wall and you been suckin’ on that one orange juice for like five hours. Buy somethin’ or get out!” That’s the G-rated version. But I loved her. Because she reminded me of just that old-school value system.

Elynor Walcott Poindexter: Ducky? We had reporters come in there and write up a story just on her, and one of ’em she framed and put on the wall. It was a scathing article, but I’m telling you people actually came just to see Ducky.

Osby: When Elynor was running the place, Wally would come in there on occasion, and he would lay cats out. “Get out of my place! I don’t like you! You’re not playing! You don’t play anything! You’re not good! You’re not worthy! Get out of here!” He would Kick. You. Out. It was brutal, but necessary. Because he was on the money. I’m all for that whole school of hard knocks, because all the people that he chastened, they wound up being exceptional musicians.

Elynor Walcott Poindexter: So many famous people—and not famous—have come to Wally’s. I was tending bar one night when Angela Davis was there. She was smoking a pipe. I’ll never forget that. You know, we never bother people when they come to Wally’s. We don’t grab a camera—just go, “Hello” and keep it moving. As my father always said, “Keep it moving!”

Trumpeter Jason Palmer playing to a packed house. / Photo by Tom Herde/The Boston Globe/Getty Images

Jason Palmer, trumpeter: [Roxbury native and legendary drummer] Roy Haynes would come down. This one time he came, he had on this big white cowboy hat and he was wearing all white, and he sat in the very back of the club, at the bar, right on the right side. So I saw him, and I introduced him to the crowd. Everybody started clapping. When there was a break, he comes up to me like, “So Jason, how did you know that was me?” And I said to him, “Roy, there’s no way you can walk in a jazz club and not have anybody know who you are. Especially musicians. When that day comes, it’s going to be a sad day.”

Frank Poindexter, son of Elynor and current manager of Wally’s with his brothers Paul and Lloyd: Paul English [the cofounder of Kayak.com] brought Bill Murray in one time and they hung out with us for about a good hour and a half, two hours. It was a Latin Jazz Night. I’m telling you, Bill was down there dancing with people he never knew before, and he was having a great time. It was unbelievable. I gave him a hug and told him how his presence would make a person’s day. He was gracious because he’s a special individual. The people didn’t bother him, just said hello. I was kind of amazed how civilized, how courteous people were—other patrons. It was special.

Elynor Walcott Poindexter: One of the things I want to do is have an event for everybody who ever met at Wally’s and fell in love. We have so many. I have heard that from so many people. “My parents met here!” “My grandparents met here!” Ralph Martin [the former Suffolk County DA] and his wife, Deborah, told me they used to date at Wally’s.

Palmer: Elynor ran the bar on Sundays when I would host the session. She was real particular about what she liked. I met Wally once before he died. I heard he could be a real hard-nose, but he was a very, very sweet man. He was a bit frail at that time.

Elynor Walcott Poindexter: My dad passed in 1998. He was 101. I got a call from Richard Evans, a jazz singer, while I was making the arrangements for the funeral. He said, “Elynor, I’m calling to let you know we would like to do a parade to honor your father.” This is out of the blue, and I didn’t have to do a thing but just say, “Yes, and thank you very much for thinking of my father and us in that way.” So when the service, at Union United Methodist Church on Columbus Avenue, was over, the streets were all blocked off, and the parade went down Columbus Avenue from in front of the church to West Newton Street, down West Newton Street, then down Saint Botolph, and then a left on Mass. Avenue. It was like a New Orleans second-line parade honoring him.

Wally’s has always been known as the place where young students of jazz earned their chops. Today, as the third generation of the Walcott family manages the club, they have plans to double down on their relationship with students as they look forward to the post-pandemic future.

Osby: Over the years, Wally’s became more of a workshop atmosphere, where we could employ techniques and devices and approaches that we didn’t do in school or in classes. It was a place you could play and do whatever you wanted without worrying about a grade.

Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah, five-time Grammy-nominated trumpeter: I am a person who grew up hearing about Wally’s. If you hear about the great players from up North, most of them came from Boston, which means they had to have stepped in Wally’s, because this is the environment where some of the greatest practitioners from that region and eventually around the world cut their teeth. The first thing I did when I got to Boston, before I stepped a foot in a classroom at Berklee, I went down to Wally’s.

Frank Poindexter: Oh, it was the same for everybody who came to Berklee—we were providing them footing in the city, a safe, family-oriented environment. And also, more important, a network of musicians.

Palmer: At Wally’s you really get to test your material out to a live audience. I can’t think of many places in the world where you can go and really hone your craft without any kind of limitations.

Frank Poindexter: They’re working on their ideas and concepts. So you have to give them a certain amount of latitude. But you can’t let ’em go bananas.

Noah Preminger, saxophonist: When you’re 19 years old and you get to go play in a crowded club, it’s a thrill. Because people go fucking nuts for you there. It’s like you’re playing Madison Square Garden for 60 people.

Scott aTunde Adjuah: There wasn’t a moment when Wally’s wasn’t a packed house.

Preminger: It’s kind of seen as a hip establishment, and it’s centrally located around a ton of different universities and just a large population of people. It’s known as a cool place to go to that has jazz. It kind of puts the word “jazz” out there as something that’s fun and okay to participate in. It makes it more accessible to a wider range of people.

Frank Poindexter: We own a building next door, and we want to create a student café so we can employ these young musicians here in Boston. Because we got this super-special ecosystem when it comes to musicians. Boston Conservatory, Berklee, New England Conservatory. You got Harvard and all the other schools that have their own music programs. Where else in the world is that happening? Then we got the apartments above it. These young people who go to Berklee, these schools, they don’t have the money for the housing. We can provide the housing for them at a discounted rate, so they can stay here and finish their education. That’s our goal.

Terri Lyne Carrington: Wally’s is a cultural institution, and it’s the only Black club that has stayed in existence like that, and it literally helped to cultivate the young Black jazz musician. Wally’s is the only one in existence, preserving the culture.

Matt Sonny Carrington: It is crucial that Wally’s survive. It’s the only club left in the jazz community and it’s just a few blocks from Berklee and the New England Conservatory. And I do think Wally’s will survive the pandemic, and you know the reason why? Because they own the building.

Frank Poindexter: We’re located where the property taxes are very expensive. You got to pay $20,000 on the building.

Elynor Walcott Poindexter: They come every quarter whether you have the business operating or not.

Frank Poindexter: We had to apply for a loan and borrow money and incur debt for an event that was not of our making. In order to remain solvent we had to take on debt, and that debt doesn’t even cover the lost revenue from March 14 until the present.

Terri Lyne Carrington: I have faith that Wally’s will survive the pandemic because we, as a people, have always had to be resilient. No one should have to be this resilient, but in the eye of adversity, over hundreds of years, we’ve figured out how to not only survive, but often thrive as well.

Frank Poindexter: We’re doing whatever we can to maintain the basics so that we have a chance when the state calls Stage 4 and we can reopen our business.

Scott aTunde Adjuah: Wally’s is a monument, one that’s held open arms for the community for decades. Whatever the community has to do to make sure these institutions thrive is what they have to do. Wally’s stays.