Bestselling Author Sebastian Junger on PTSD, Mortality, and His Near-Death Experience in Truro

After writing about shipwrecks, war, and a serial killer, the Belmont native and Perfect Storm storyteller's latest book delves into something completely new: nearly dying on the Cape.

Junger in March 2024. / Photo by Ty Mecham

You might assume the scariest moment of Belmont native Sebastian Junger’s life happened while he was a war correspondent in Bosnia or Afghanistan. You’d be wrong. Most famous for writing The Perfect Storm—a journalistic account of a doomed Gloucester fishing boat that was made into a movie starring George Clooney and Mark Wahlberg—this week, the author and Oscar-nominated documentary filmmaker is releasing In My Time of Dying, a book about his 2020 brush with death from a ruptured aneurysm at his Truro home. Before his book tour brings him to Gloucester City Hall’s Kyrouz Auditorium on May 23 and Cambridge Public Library on June 25, Junger spoke to us about war, fatherhood, and grappling with the afterlife.

Was it difficult to write about something so intensely personal in your new book?

Yes. It was incredibly traumatic. I waited a couple of years. I couldn’t have written about it immediately afterward. Writing about the medical stuff was weirdly fascinating and not that upsetting. What was hard was writing about the psychological consequences, which were pretty debilitating. I had anxiety disorder and depression, and I’m not prone to either. I really didn’t recognize myself. And writing about that was hard, but I love the process of writing so much. When I find the perfect words to capture something, there’s such an intoxication that it sort of overrides my discomfort.

Junger’s newest book, out May 21, 2024. / Courtesy

If you could boil it down to just one thing, what do you hope people take away from the book?

That none of us knows for sure that this won’t be the last day of our lives, so what are you going to do with it? If you live like that, you’ll have, in all likelihood, a good life and will act well toward others.

Going back a couple of decades to your first book—The Perfect Storm wasn’t exactly what you set out to write, was it?

No. Originally, I was going to do a collection of essays on dangerous jobs, but my agent convinced me to focus on one story. I wrote a piece for Outside magazine about the storm and the Andrea Gail, and my agent said, “Listen, I sold that magazine article as a book,” and it was like they called my bluff. I had no idea how, as a journalist, I would fill in this whole narrative where we really don’t know what happened to the boat. I didn’t know how I was going to manage that, but I found some salvation in The Hot Zone by Richard Preston. He used this really cool technique where he would say to the reader, “So-and-so may have been thinking this or may have been looking at the sunset, but what we do know is that by morning, he was dead.” It’s totally honest. He’s not fictionalizing anything, but he’s able to fill in some narrative gaps that otherwise we just don’t have information about. Conjecture is fine, as long as you call it that.

Were you surprised by its success?

I mean, if I can be totally honest, I thought I’d written a really good book and that, in a reasonable world, it would be a bestseller. [Chuckles.] Many authors think that, right? I was using journalistic standards that I got from writers I admired, like John McPhee and Peter Matthiessen, sort of using them as benchmarks. But I was utterly unprepared for the level of success it had. It never occurred to me that it’d be that big, but then, I didn’t know anything about publishing, either.

Have any of your other books come about as serendipitously?

Well, my next full-length book was A Death in Belmont, which hinges on the fact that the man who confessed to being the Boston Strangler, Albert DeSalvo, worked for my family as a carpenter during the time when he was killing people. So that was serendipity in a way, right? That story was in my family for a long time, and then I thought, “Okay, maybe I’m going to re-investigate that.” DeSalvo was in our house in Belmont and had to drive by the house of one of the murder victims to get home every day. In the end, I had to write a book that didn’t come to a definite conclusion. It says, “Okay, you’re the jury. What do you think?” Because I don’t know. It was very, very hard to make that ambiguity dramatic or fulfilling.

Did you watch the movie Boston Strangler?

No. I don’t watch a lot of stuff. I don’t even have a TV.

What adjective would you use to describe your career?

I don’t know if I could come up with one word, but I would say that I’ve always worked on things that were so interesting to me that I would do that work for free. These stories are just so compelling to me. They’re central to my interest in the world and my sense of myself. That I get paid for that and can make a living off it is just an insane miracle.

Why did you decide to become a war correspondent?

I went off to Bosnia in 1993, before The Perfect Storm was published, because I was tired of cutting trees, which is what I’d been doing. I’d cut my leg with a chainsaw high up in a tree, and I thought, Well, that’s not going to be the last injury I’ll get doing this. Anyway, I went off to Sarajevo. I’d heard that freelancers could go there and pick up assignments, and I could do a kind of quasi-journalism school, and I totally fell in love with it. I fell in love with many things about it, but one was just a sense of meaning, like, “Wow! The world’s pain and drama are unfolding right here around me, in front of my eyes, and I’m one of a fairly limited number of people who are telling everyone else in the world about it.” It totally addicted me, and it wasn’t the adrenaline or the stakes involved, though they do put an edge on things. It was a sense that I have a small but meaningful place in the world.

How did you guard against PTSD?

Well, it’s like, how do you guard against grief if your wife dies? You don’t. It’s just a psychological process, how your body finds its way to health after something really painful.

In your book Tribe, you examine why some soldiers feel a longing for combat or at least the camaraderie of it.

People are inevitably drawn to community. American soldiers come back from a deployment where they’re in a platoon; they’re in close proximity to 30 or 40 other people and function as a unit. It has all the elements of a tribal group. And they lose that when they come back to society. If it were a healthy society, they’d be rejoining other close communities, but we’re a highly technological, mechanized society where there’s nothing to be part of. For some pretty compelling evolutionary reasons, that’s terrifying. Humans do not survive by themselves. They die. Part of PTSD is often the transition back into a situation where you don’t feel safe, because no one needs you. You’re not part of anything. There’s no primate that likes that, including humans.

Photo by Ty Mecham

Why did you choose to be a contributing editor covering war for Vanity Fair over, say, the New York Times or any number of other publications? It seems like they do best with glamorous subjects, not necessarily serious ones.

I wanted to reach those readers. They were the people who, in my grandiose opinion at the time, needed to think more seriously about the world. The New York Times and the New Yorker, etc., were already doing that. But before [editor in chief] Graydon Carter reached out, it would never have crossed my mind. He said, “Look. We can pay you well. We can give you a huge platform. And you can do anything you want.” I wouldn’t have gotten that at any other publication. And it might be the glitz and the beauty that gets someone to pick up the magazine, but if I could bring Kosovo to that person, and they think, “I’ve gotta do something about that….”

Best movie about war?

It’s hard to come up with just one. There was an amazing movie that came out right after World War II called The Best Years of Our Lives. It’s about veterans coming home, and you think the title is ironic. You just assume it’s like, “They stole the best years of our lives from us.” And then you realize these guys don’t want to go home. It’s a profound, amazing movie of the era.

How did you feel about The Perfect Storm as a movie?

It was a $120 million Hollywood production, and it had all the pleasures and delights and deficits of that. It was enormously fun to watch it, and it was extremely respectful of Gloucester and the fishing community in general, for which I’m eternally grateful. But, you know, you’re very aware you’re watching George Clooney. You never lose sight of that essential. [Laughs.]

Did you attend the Oscars when you were nominated for Best Documentary?

Yeah, of course, I went to the Oscars for Restrepo.

Was it fun or uncomfortable? I’ve heard people say they’ve never had to pee so badly, because they’re in a car for four hours to drive two blocks.

It was everything. It was surreal. For the uninitiated, Hollywood at Oscar time is just another planet. Everything about it is so over the top. It’s fun for a blur of 30 seconds, and then you’re out the other side.

You’ve written in some pretty horrific conditions. Can you write just about anywhere, or do you have to have things a certain way?

As a journalist, you’re constantly taking notes in a field notebook. I don’t have a smartphone. I have a flip phone. I don’t take notes digitally, ever. So I write things down, and sometimes the notes approach a level of elegance that’s almost prose. Not always. Often, it’s just scratching out information. But the short answer is yes. I can sit down on a rock after a firefight and write a pretty good paragraph about what that felt like. As for the actual end product of a book or a magazine article? That’s invariably done at home at my desk, and if there’s a jackhammer outside, I can deal with that. That’s not difficult for me. My wife remembers I was editing a draft of a chapter while standing up at a kitchen counter, holding our six-month-old, who was crying. So yeah, I can get it done.

Most scared you’ve ever been?

I’ve had moments of considerable fear. Once, in Nigeria, someone told me that he was going to kill me, and he had the ability to. I was completely in his power. And in Sierra Leone, there was a similar situation. But real fear was after I had the aneurysm rupture, there was some speculation by the doctors that I had pancreatic cancer. I spent a summer where I didn’t even recognize myself. I was so scared.

You’ve always said that you’re an atheist. Did the ruptured aneurysm change your belief in God, religion, or the afterlife in any way?

With God and religion, I’m still an atheist, and a damned atheist, if you will. But when that happened, I saw my father. I didn’t see God. I didn’t see Jesus. I saw my dad, which made me think that maybe the human brain’s pretty creative in its hallucinations or that at some subatomic level, the way reality works and the way life and death relate to each other is something we really don’t and maybe aren’t capable of understanding. And that after we die physically, there is some lingering, quantum information involving that person that we just don’t understand. I’m sounding vague and clumsy because, of course, these are unknowable things. But as an atheist, it made me think it’s possible that we know nothing. There’s a line in my book that we may have the same understanding of reality that a dog has of a television screen.

Photo by Ty Mecham

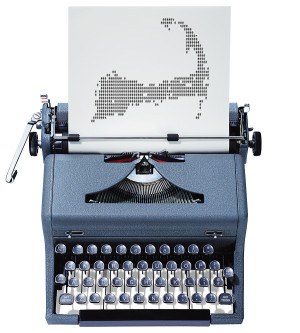

By the Numbers

Writers’ Retreat

The Cape has always been a hub for famous authors—at least part of the year.

11 million+

Number of copies of books in print by Jennifer Weiner, who owns a home on the Outer Cape.

1975

Year Annie Dillard, who lives part-time on the Cape, won the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction.

4

Number of years literary icon and longtime Cape Cod resident Kurt Vonnegut owned and managed a Saab dealership in West Barnstable, while trying to get his writing career off the ground.

1916

Year playwright Eugene O’Neill debuted his first production in Provincetown, which he called home for years.

53

Number of books written by Paul Theroux, who splits his time between Cape Cod and Hawaii.

First published in the print edition of the May 2024 issue with the headline, “Back From the Brink.”