Is Candlepin Bowling a Dying Pastime?

In the shadow of gleaming new condos, the close-knit community inside Eastie's Central Park Lanes tries to keep its 67-year-old league alive. When the last pin finally falls, what happens to the social connections that once brought neighbors together?

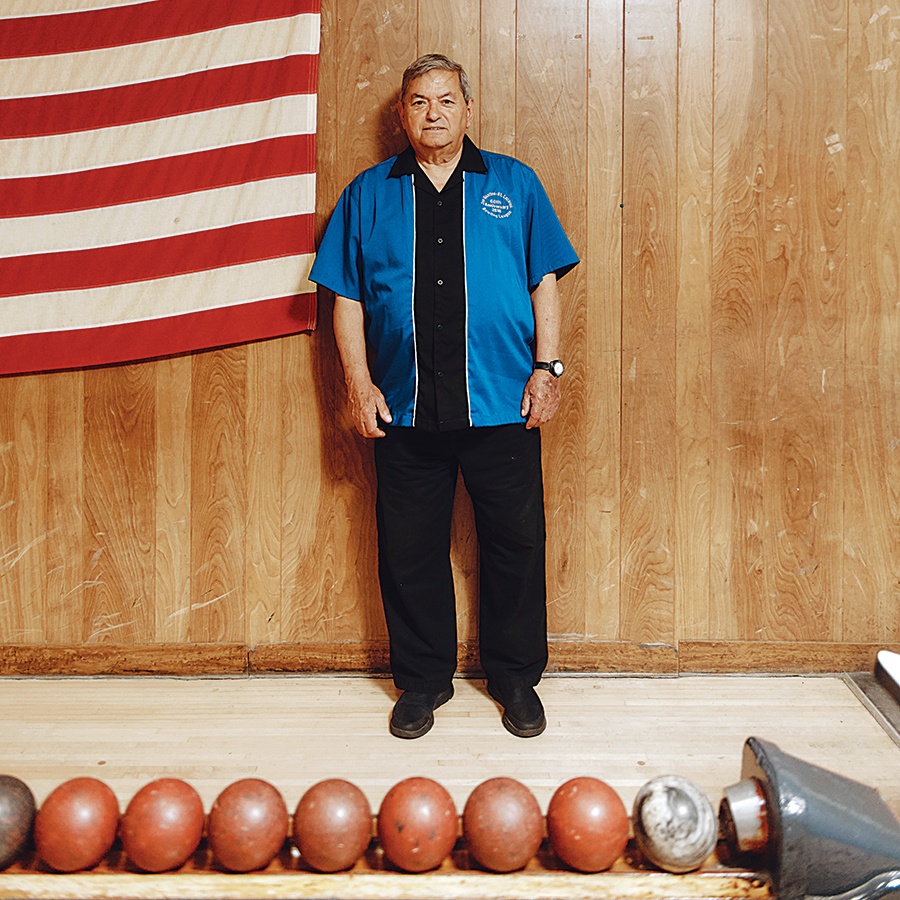

The Joe Guarino/St. Lazarus Bowling League started in 1957. / Photo by Tony Luong

It’s 6 o’clock at night, and inside East Boston’s Central Park Lanes, the late-summer air is heavy and humid. Pulling a handkerchief from his pocket, Nunzio “Nunny” Celona wipes his forehead as he stands at the top of the lanes on the second floor of the bowling alley. He signals for someone to shut off the lights that illuminate the pins.

“Can I get everyone’s attention?” Celona shouts in a commanding voice.

His smooth, olive-skinned round cheeks, dark hair mixed with gray, and wide brown eyes belie his 81 years. Though he may move a little slower than when he first joined the Joe Guarino/St. Lazarus Bowling League in 1964, he exudes assurance and control. Nearly 50 bowlers, dressed for comfort in sweatpants, jeans, and T-shirts, all move toward him to listen, forming a semicircle around the lanes. They’ve been summoned for a moment of silence to honor one of the bowlers’ grandmothers.

Gathering around to offer a prayer for a member’s loved one is not as unusual as it might sound for this group. After all, family and close connections to the neighborhood where they grew up are important. Celona and the rest of the bowlers bow their heads.

After a brief hush, Celona says loudly, “Thanks, everyone. I want to remind anyone who hasn’t paid their dues to see Stevie before you leave tonight.” Then he asks the team captains to huddle with him separately to discuss the season schedule, telling them that a couple of bowlers won’t be back for the season due to illness. Finally, Celona offers a message of encouragement before the games begin. “Let’s have a good night, guys. Let’s bowl.”

Nunzio “Nunny” Celona has been president of the Joe Guarino/St. Lazarus Bowling League since 1989. / Photo by Tony Luong

When Central Park Lanes opened in 1950, tight-knit leagues like this one were commonplace. In fact, within 10 years, demand for the uniquely New England version of bowling known as candlepin—the game uses smaller balls without finger holes and thinner pins that are not cleared between rolls, allowing for three rolls per frame compared to ten-pin bowling—was so strong that owner Angelo Vozzella added a second floor and 10 more lanes.

Today, it feels more like a quaint scene from a bygone era. For many Bostonians, at least, the days of being part of a group—whether through a bowling league, church, synagogue, or charitable organization—are over. The majority of Boston-area residents say they never or seldom attend religious services regularly, according to a recent survey. And like many pastimes that once appealed to young people and families, candlepin bowling has seen the number of participants diminish over the past few decades. At its peak, hundreds of candlepin bowling alleys spanned across the region. Now, in 2024, Central Park Lanes, or CPL as it’s called by locals, stands alone as the last bowling alley in East Boston, which had at least four when Celona started bowling in the league. League bowling, in particular, has become markedly less popular, according to Harvard political scientist Robert D. Putnam, who penned the 2000 book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community.

Candlepin bowling balls are significantly smaller than traditional bowling balls. / Photo by Tony Luong

East Boston itself is also changing. In CPL’s early days, large Italian families filled the surrounding three-decker row houses in the neighborhood, where mom-and-pop bakeries and butcher shops were a staple. Beginning in the 1980s, due to geopolitical forces, Latin American and Southeast Asian immigrants arrived and settled in East Boston, moving into an affordable neighborhood where they could find work easily. By the ’90s, many working-class, less expensive Boston neighborhoods had already been or were being gentrified, but somehow, East Boston remained a melting pot of newcomers, all of whom shared the same dream—making a better life for their families.

Today, though, Eastie—like much of the city—has succumbed to the pressures of real estate riches. Many of those three-deckers have been converted into ritzy condo units, and just a block away from Central Park Lanes, a large luxury residential building is under construction. CPL is one of the few small businesses in the area that’s stuck around since the ’50s.

As such, Chucky Vozzella, who spent most of his life in the bowling alley and took over for his father when his age and health began to slow him down, often receives calls from developers asking him to sell the property. Chucky’s kids are not keen to keep the family business alive. Yet at almost 70, Chucky insists he isn’t planning to retire anytime soon from the only job he’s ever known. “I don’t know what I’d do,” he says. “During the COVID thing, I was going crazy staying home.”

Once he does call it quits, though, Chucky knows that finding a buyer won’t be a problem. He also knows that Central Park Lanes will likely cease to exist—and that the ever-changing neighborhood of Central Square in Eastie will change once again when that day comes.

Central Park Lanes owner Chucky Vozzella has spent most of his life in the bowling alley. / Photo by Tony Luong

On this random Thursday night, the lack of air conditioning inside CPL doesn’t stop the Joe Guarino/St. Lazarus Bowling League members from showing up. They’ve been meeting every week for more than 65 years. Most of the league’s teams go upstairs to the second-floor lanes. Four teams, though, stay on the first floor and take lanes one through four. Chucky, watching attentively from behind the counter where he hands out bowling shoe rentals, yells to one of the bowlers who is pushing the reset button over and over.

“Wait, wait! I got it.”

Chucky quickly jogs over to the lane and ducks under the overhang where the pins seem to magically appear and disappear with the help of a mechanical pinsetter. He climbs up, and soon his feet come down a few lanes over. A pin is stuck and jamming the pinsetter. After a few moments, he emerges from the narrow space at the end of the lanes and walks back to take his place behind the front desk.

League members hit the lanes. / Photo by Tony Luong

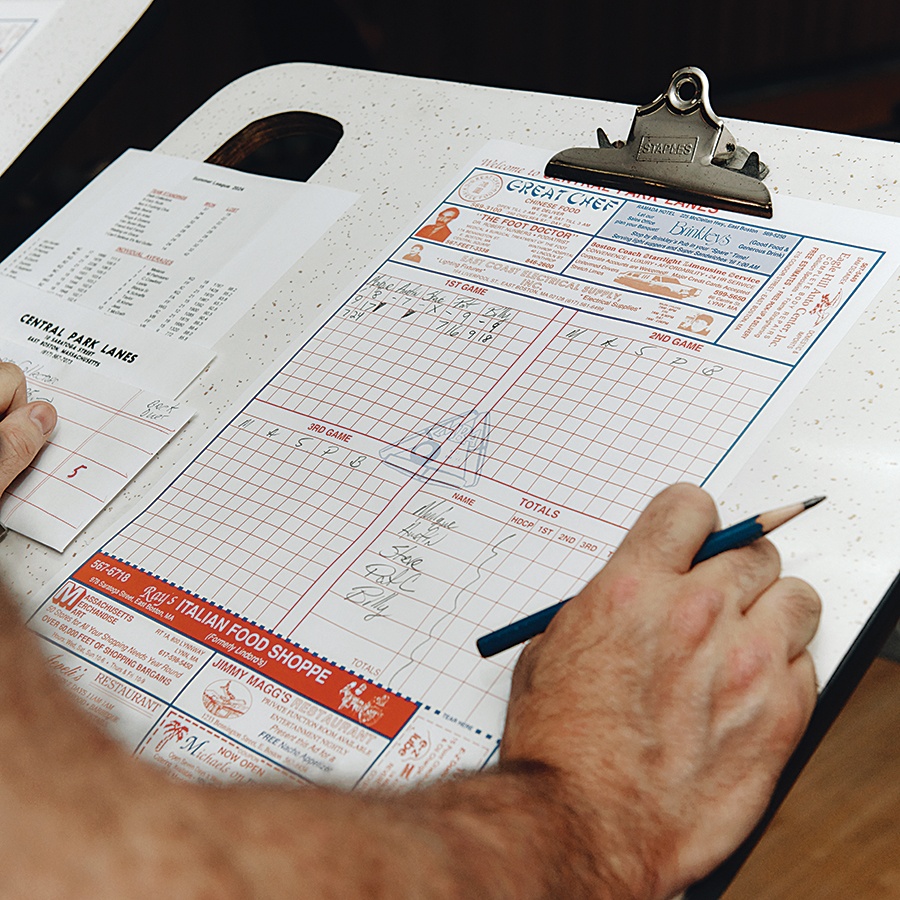

All around, bowlers are reminded of eras past. On the faded blue overhang above the lanes, hand-stenciled signs in bold lettering read, “Please Do Not Lob the Ball” and “Please Respect the Foul Line.” The walls are covered with a light-wood paneling that was ubiquitous in midcentury-modern design. Hard plastic benches sit at the top of each lane, while glass block windows surround small manual-open windows that were installed to help with ventilation. One of the bowlers pulls down a handle to try to get some air flowing on CPL’s low-ceilinged second floor. Team members holding little pencils take turns keeping score on scoresheets that are placed on Formica-topped podiums with heavy metal bases. There is nothing digital or electronic, except for the lottery and Keno machine that was installed in the ’90s when the game was first introduced in the state. As the streetlights on Saratoga Street come alive, the Joe Guarino/St. Lazarus league bowlers begin warming up by throwing practice balls before official play begins.

Keeping score the old-fashioned way—with a pencil and paper. / Photo by Tony Luong

The league formed as a social group at St. Lazarus Catholic parish in the Orient Heights section of East Boston, and Celona says his close friend Joe Guarino was one of the original bowlers who started the league in 1957. They were in each other’s weddings, and Guarino served as league treasurer. “Joe was the bowling league,” Celona says as he recounts the night when Guarino dropped to the floor on Alley 19 from a heart attack just as they’d started bowling. A fellow league member administered CPR. An ambulance whisked Guarino away, but after some time in the hospital, his heart gave out, and he died. “He was there from day one,” Celona says. “I proposed that we change the name to Joe Guarino/St. Lazarus.”

Keeping a connection to the past is important to Celona and many league members. They return each season knowing almost all of their teammates and opponents will be coming back, while also trying to recruit new players to keep the league going.

Some league members have bowled in other leagues and at other bowling centers, but there’s something special about this place and this league, says Steve Passariello, who has become a bit of a salesman for the Joe Guarino/St. Lazarus league. He updates its Facebook page, posting the latest standings and reminders about paying dues. When the league began to hemorrhage members due to illness and death, he recruited all four of his teenage sons to play with him.

The average Joe Guarino/St. Lazarus member knows a thing or two about life (and candlepin), but true believers like Passariello are constantly concocting ways to breathe life back into the league. For him, it’s a passion that started with a cryptic invitation. After attending a wake with his future wife, her brother asked him to meet at a building in Woburn. “So I show up at this building,” Passariello says. “I’d never been there. I didn’t know the building existed.” Now in his early fifties, with wire-rimmed glasses and a shaved head, he still sounds like an excited teenager when talking about candlepin bowling. “So he pulls up, and I’m like, ‘What are we doing? Are we putting a body in the trunk, or what’s the story?’ He goes, ‘We’re going bowling.’ I say, ‘Bowling?’ He says ‘Yeah. You bowl candlepin?’ So we go in, and he’s telling me, ‘You’re joining a league.’ Suddenly, I’m in this bowling league, and the rest was history. That was back in September 1996.”

Passariello’s passion hasn’t waned. He’s even been thinking about adding another night or two of bowling to his regular Thursday night schedule. He likes it that much and thinks everyone should try it. He also cares about keeping the league alive and enjoys the simplicity and atmosphere at CPL. He’s a family guy, and having his four sons bowling in the same league makes him happy—yes, for the future of the league, but also because he likes knowing his sons aren’t out getting into trouble or playing video games.

Celona’s love affair with candlepin bowling stretches back even further. Before he joined the league in the ’60s, the teams bowled at the Orient Heights Bowladrome. Over the first decade or two, the league moved around to other bowling alleys that are now long gone. Central Park Lanes became its home before Celona took over as president in 1989. He became president by default after being approached by the former president, Stephen Mazzarella. “[He] didn’t want to be president anymore,” Celona says. “Nobody wanted it. He asked me if I’d be interested. I said, ‘Well, if nobody wants the job, I’ll take it.’”

When Celona took the reins, he was handed the league rule book, which he still has, even though it’s a bit yellowed and faded now. Neatly typed in all-caps font, with a few handwritten additions, on plain white paper are the rules of the Joe Guarino/St. Lazarus Bowling League. Following prescribed protocol that hasn’t changed much over the years is not unlike other social groups that have struggled to keep up with the faster pace of the digital age. After all, there’s comfort in that sameness that some people like to embrace.

Photo by Tony Luong

Candlepin bowling as a sport never grew much further than New England. Maine bowler and filmmaker Ricky Leighton—who made the short film Candlepin: the Documentary in 2022—speculates that is one of the reasons the sport is dying out. Then, of course, there are the logistical challenges: “[The bowling centers are] extraordinarily expensive to maintain—you’re talking about large structures with really big roofs that are prone to problems,” he says. “And on top of that, you have heavily dated equipment that requires essentially a mechanic to work on and to fix,” he says.

While that kind of old-school nostalgia may be an attraction for a lot of bowlers, there is a difference between neglect and authenticity. Leighton recounted a story about bowling in an older bowling center and rain coming through the light fixtures and dropping into his friend’s beer. “It’s become a lost art,” he says. “The ones you do see succeeding are usually the family businesses.”

Photo by Tony Luong

Many candlepin centers also took a big hit when COVID struck. Being in the city of Boston meant Chucky Vozzella had to keep Central Park Lanes closed for longer than some surrounding towns’ small businesses. And if he wanted to open again, he had to follow health guidelines by installing Plexiglas dividers and Purell dispensers. For him, it was more than the loss of income—it was the loss of routine and the social aspect of the business that he felt most. “I was used to being down here seven days a week,” he explains.

He’s not exaggerating: Chucky has spent his entire life at Central Park Lanes. He and his family lived in East Boston, too, when he was young but moved a few towns north of the city before starting high school. Chucky explains that in candlepin’s heyday, Central Park Lanes was a busy place catering to all ages and groups: “We used to be jammed with leagues—we had to double up. One at 7 p.m. and 9 p.m. A lot of workplace-associated leagues.” Today, Central Park Lanes still hosts leagues most nights of the week, and Fridays and Saturdays can be busy, but it’s not like it used to be.

For Passariello, there was an obvious, long overdue solution when membership started to drop off during the pandemic. “I’m like, guys, why don’t we start looking at allowing women into the league?” Though the Italian-American debt consultant is one of the league’s younger bowlers, in his fifties (the oldest members are in their eighties), he was well acquainted with the men-only mindset of the older guys—he’d grown up with uncles and cousins just like them. But it wasn’t the 1950s anymore, and he was trying to make the older bowlers understand that if they were to survive, the league needed to fast-forward into the present, too. Acknowledging how woefully out of step the league was, he explained that a lot of the older men were afraid they wouldn’t be able to be themselves and would be inhibited when it came to using curse words or making off-color jokes. “I said, ‘Listen, people are people, and if it is that type of an atmosphere, they’re going to like it and stay, or they won’t. But…we could use the membership.’”

Passariello had long heard from one woman via Facebook who wanted to join the league. He only knew her through another friend, and he’d put her off as long as he could. He could not easily explain to her that this was a “men’s only” league, just as it had been since its inception in 1957. He knew the members needed to change, he said, yet it took a few years to convince some of the older members. “So we took a vote on it, and the night we voted on it, there were a couple of members that didn’t want it, and they said if we allowed it, they would quit,” Passariello recalls. “They ended up quitting because we approved it.”

After the vote, most of the members—even the older ones—stuck around and now the league includes half a dozen women. Still, it’s hard to imagine, for younger people who might be interested in joining the league, that even up until just a few years ago, women weren’t allowed to join.

Steve Passariello has made it his mission to recruit new members. / Photo by Tony Luong

Celona says that Chucky is doing the league a big favor by keeping the fees to just $7.25 per bowler for three strings of bowling at Central Park Lanes. Celona once considered playing in a league closer to his home in Wakefield and spent an afternoon at a bowling center in Woburn. He asked about the price and found they charged by the hour, which would cost a lot more than what he pays at CPL. He also didn’t like that they had synthetic lanes, rather than wood, and that the center’s owner wouldn’t let him use talcum powder on the approach, making it impossible for him to slide with his bad knee. So he chose to stick with Central Park.

Like old pals who finish each other’s sentences, Central Park Lanes and the Joe Guarino/St. Lazarus Bowling League understand each other, sharing a vibe and a history that the new kids on the block just can’t replicate. Any bowling lanes that spring up today are usually part of a larger entertainment complex, and most include a large bar area, a restaurant, pool tables and arcade games, and lots of flashing lights and music. Those places can be a lot of fun if you’re looking for a night out with friends or throwing a party. But it’s hard to imagine a league of bowlers pausing for a moment of silence after the loss of a member’s grandmother in a place like that.

Part of the charm of the Joe Guarino/St. Lazarus league is that it isn’t a social activity that revolves around drinking. The organization, at one point, decided to ban alcohol consumption while playing. “We reinforced it. Nobody really ever drank,” Celona says. “Maybe somebody would occasionally spike their Coke.” But after a couple of bowlers started a regular habit of drinking before coming to the alley and kept drinking while there, it concerned Celona that they could be held liable if something happened. When they cracked down, the bowlers who really wanted to drink started their own league. That group eventually petered out, while the Joe Guarino/St. Lazarus league is still bowling. Says Celona self-deprecatingly, “We got rid of most of the a-holes; the only one we have left is the president.”

He believes that people stay in the league and come back to bowl for the chance to win a little bit of prize money, to enjoy the annual banquet, and to see their name emblazoned on the Stanley Cup lookalike trophy if they win. Besides the tangible things Celona believes they come for, it’s clear that most members continue to bowl because they enjoy the camaraderie each week. For some, it’s the one day of the week they get out of the house for a little bit of exercise. It keeps them engaged and part of something.

Before COVID, members of the league socialized outside of Central Park Lanes even more than they do today, even taking a couple of buses down to Foxwoods Casino as a group. But since then, the cost of bus rentals has increased dramatically, and Foxwoods stopped offering special discounts for groups like theirs, making it less appealing.

The truth is, even though they may not say it to one another out loud, Celona and some of the bowlers who want to keep the league going, like Passariello, seem to worry that the league, and Central Park Lanes, may cease to exist someday. “I think the clock’s ticking…because Chuck’s family, when they hit a certain age, I think are going to sell it,” Passariello says. “They’ll offer them so much money for that space. They’re going to be left no choice but to just sell off the building, and it’ll come to a close. And it’ll just happen quickly, unfortunately. But personally, I’d love to continue to bowl. As long as there’s an opportunity to do it, I’ll do it until I’m physically unable to do it.”

The scene on a hot Thursday night. / Photo by Tony Luong

Chucky is leaning on the counter, watching the league’s four teams play and only half-listening to one bowler who keeps walking away between his turns to roll. After a minute, Chucky yells out to one of the young players known as “the Hammer.”

“You’re breaking the rules.”

The Hammer looks at Chucky, a bit confused.

“You guys keep breaking the rules,” Chucky shouts over the din of the rolling balls and crashing pins.

He pulls out a little pocket-size book and calls the player over to show him the rule they’re breaking. “You both have to be up there bowling at the same time,” he tells them, referring to the need for a player in each lane. “You can’t bowl alone.”

First published in the print edition of the August 2024 issue with the headline, “You Can’t Bowl Alone.”