Dane Cook Could Use a F#%ing Hug

It’s 10 a.m. in Beverly Hills, and I’m sitting on the patio of one of those big, modern movie-star houses. Pool. Hot tub. A lawn that disappears into the horizon. The city below. Sitting next to me is the guy from Arlington who owns the place, Dane Cook.

The house is perched on a cramped hillside so tangled with money and power that one resident a block down the road has erected a sign urging everyone to turn down their music, to be respectful, to share the hill. “No matter how important you might be,” the sign says, “we are all the same.”

Cook’s house is at a slight remove from whatever mayhem may occur down the road. It’s fortified on three sides by walls that preserve a sort of secluded loveliness; it feels like being on an airplane, nothing but the view stretched out below.

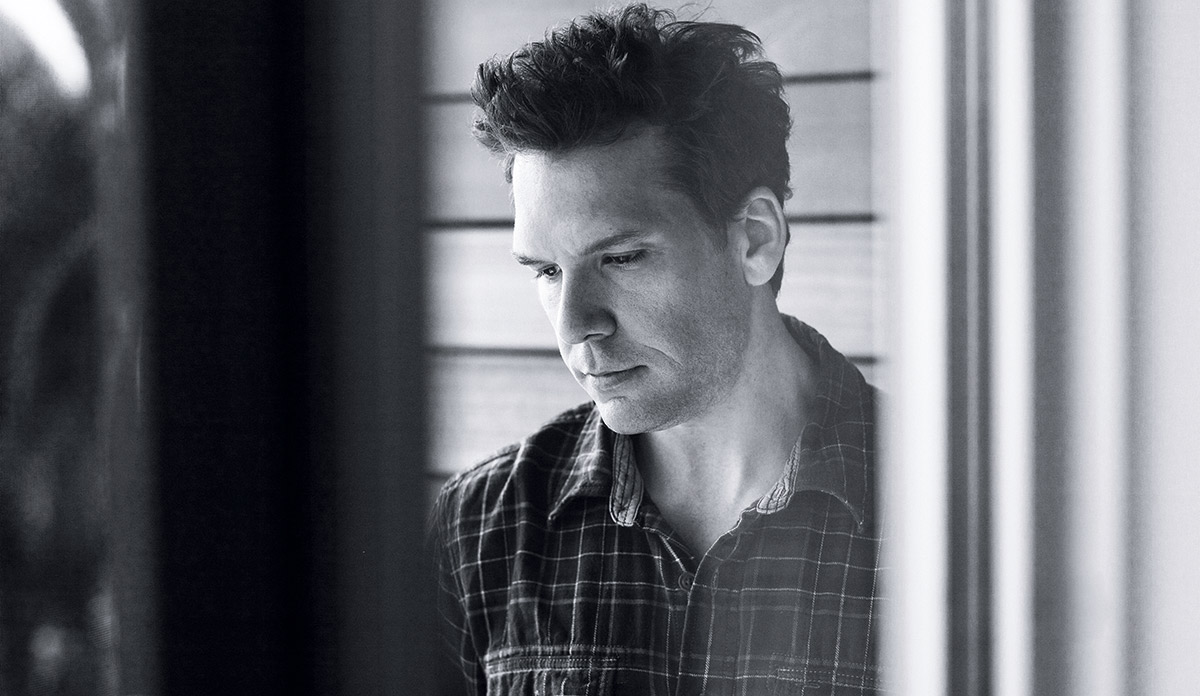

Cook’s 37 now, but he looks and plays younger. He’s barefoot, and it seems as if he just woke up. Or perhaps it’s only that he doesn’t really want to do this, doesn’t want to sit out here and dredge up the past couple of years. He’s got on a black T-shirt, jeans, and a Red Sox hat. “I have way too many of these,” he says, grabbing the hat by the bill. But this one is special. Cook had it on in 2004, in the stands at Game Four of the World Series in St. Louis. “I got the tickets the night before from basically a scalper that I found, and took my dad,” he says. “First time I’d ever seen my dad jump up and down in my entire life.”

But that feels like a million years ago. His dad was still alive then. And Cook had yet to become the phenomenon that is, well, Dane Cook. Within a year, he would explode onto the scene as the biggest standup comedian in America.

Of course, that rise would prove wildly polarizing. He would inspire passionate factions of supporters and detractors. This you already know. The thing you maybe don’t know is that just as Cook was hitting it big, fate was rearing back to deliver a kick to the balls. First, his mother, Donna, got cancer shortly before he came home to play a sold-out show at the Garden. Then, a week after his mother died, his father, George, called to say he had cancer, too. He was dead within 10 months.

Earlier this year Cook released an album on which he grapples with these things—being hated, losing his parents. “What I’ve learned through all of this, through thick and thin,” he says in one of the more reflective moments of the set, “the only thing that really matters, really, is family.”

But when Isolated Incident came out in May, the album already felt dated, its title bitterly ironic. By then Cook had learned he was an apparent crime victim, allegedly robbed of millions—by his own brother. Betrayal, by its very nature, hits you unaware and sucks the wind out of you. Like his neighbor’s sign said, No matter how important you might be, we are all the same.

There’s a word that seems to stick to Dane Cook, and it is not a nice word. That word is “douchebag,” and if you sniff around the Internet in search of what passes for Dane Cook commentary, you will find that word several thousand times. Cook is aware of his immense unpopularity; he knows all about “the haters,” as he calls the vast horde of otherwise rational Americans who devote a considerable amount of their free time to expressing seething contempt for him. On his latest album, he talks about a time he tried to Google his own name. “Google was like, ‘Are you sure?'” he says.

After perusing the vitriol and sampling the angry videos that suggest he die, he says, he found himself blurting aloud, “You know what? This Dane Cook is a douchebag.”

Part of his problem is that for as long as we’ve been aware of Dane Cook, we’ve been aware of “the success of Dane Cook.” He arrived in 2005, unannounced and impossible to ignore, like bird crap on your shoulder. The very first thing we were told about him was that he was the biggest comedian in America. He exploded so fast that there was little talk of his years spent in rattrap clubs honing the craft and cultivating fans. Cook went from unknown to overexposed overnight. His second album, Retaliation, went platinum twice and shot to number four on the Billboard charts, the highest position for a comedy album in nearly three decades. This got him cast in a string of Hollywood flicks with beautiful women. It also got him named by Time magazine as one of the 100 Most Influential People in the World. He played Madison Square Garden twice—in one night. Do you know how to become one of the most reviled people in America? Get yourself ordained as the most popular something, over and over again.

When the backlash came, it wasn’t just the knuckle-draggers out there on the Web taking their shots. Critics pronounced his style simply unfunny. Rolling Stone, for instance, wondered with exasperation, “How can any comedian get this famous with no jokes?” It was observed that his bits lacked the intelligence of an Eddie Izzard, the cultural depth of a Chris Rock. His comedy, it seemed, wasn’t about anything at all. He was pooh-poohed as nothing more than a slick marketer who managed to use online tools like MySpace to rack up collegiate devotees. And he was dismissed as a purveyor of gimmicks (see, for example, his “super-finger,” a hand gesture he devised, and later trademarked, for those times when the middle finger just isn’t enough; his fans throw it like a gang sign).

But—and this is a very important but—he has millions and millions of fans. Young people, particularly those in that confused decade between their first feel-up and their first wedding, pack arenas and fall over themselves laughing at his juvenile bits. Cook’s comedy works because he positions the comic and the audience together as like-minded observers of some bizarre situation or absurd hypothetical—watching a guy get hit by a car, being involved in a heist—and finding a common dirty insight in the shared experience. Cook’s fans smile to themselves and admit, “Totally, bro. I’ve always secretly wanted to see someone get run over, too. I know exactly how you feel.” Of course, that’s just comedy. An act. When the most surreal situations crop up in real life, sometimes you’re all alone.

One Hundred Federal Street. Downtown Boston. The “pregnant building,” that grotesque slab of dark granite with the bulging gut that hovers over the street like a movie prop ready to bury you. It’s a menacing street, all skyscrapers and shadows. In the summer, the girls in the flower booth on the corner will tell you, the block gets maybe 20 minutes of sunlight. It’s darker in December, as it was on December 5 of last year, the day Darryl McCauley entered the Bank of America branch on the ground floor.

McCauley was wearing a sweater and a baseball cap, and when he walked out of that bank carrying $3 million in cash, it was the last theft in an $11 million scheme that had been going on for years, prosecutors say. Except McCauley wasn’t robbing the bank. He allegedly was robbing his little brother.

Back when Cook started making it big, he did some nice things for his family. He bought houses for his parents, and he hired his half brother, Darryl McCauley, to be his “business manager.” McCauley is seven years older than Cook, grew up in the same house in Arlington, buried the same mother; he was, Cook told me, an important part of the inner circle, one of the guys you trust to have your back.

McCauley’s a big fella, 6-foot-1, 270, and he’d spent a decade as a corrections officer at MCI Walpole, where his file was stuffed with commendations for handling bad guys. Cook already had a bunch of people tending to his career out in L.A., and a money manager in Quincy, Joe Shadduck, who dealt with the finances. But still he broke off a nice little piece for his brother—$150,000 a year before McCauley’s arrest—and gave him the task of getting the money to the bank, making sure the bills got paid and the taxes got filed. McCauley was able to work from his home in Wilmington. “It didn’t seem like a very difficult job,” Shadduck would tell the grand jury.

You can live a pretty decent life on $150,000 a year. Of course, there’s a whole other lifestyle you can lead with lottery bucks, the kind of cash McCauley used to see on his brother’s books. And by 2008, those books had become something of an issue. According to prosecutors, Cook decided he wanted to move McCauley’s job out to L.A. with the rest of his business interests, and asked McCauley to send the financial records to his new business manager. There was talk of finding another job for McCauley in Cook’s organization. But McCauley allegedly balked at the request, wouldn’t send the books. Cook wondered what was going on.

Though McCauley’s lawyer, Robert M. Goldstein, has refused to allow his client to talk, he insists McCauley never withdrew money without Cook’s approval. “This is a family dispute over finances,” Goldstein wrote in a bail filing. Cook is similarly barred from speaking about the case against his brother. But Massachusetts Assistant Attorney General Richard D. Grundy, who is prosecuting the case, has presented to the court a detailed narrative of what he says went down. The state alleges that once the comedian had hired a replacement for his brother, McCauley asked at least two people to help him “find skeletons” in the closet of his successor. McCauley continued to ignore pleas for his brother’s financial records, and on November 20, 2008, according to Grundy’s court filings, McCauley sent a text message to his wife asking, “Will you be available to travel the world with me in 2009?”

Four days later, McCauley wrote himself a check for $3 million from Cook’s account, signed his brother’s name to it, and deposited it into his own account. Prosecutors wonder whether McCauley was by then growing fearful of being caught—on the morning of December 4, they say, he researched “white collar, attorneys” on the Internet, printing out biographies on approximately 40 lawyers. He also allegedly asked Bank of America to deliver withdraw $3 million in cash to his home, a request the bank declined, citing insurance reasons. The bank eventually told McCauley he’d have to come downtown to get his money.

The next day, December 5, just a few hours after walking out of the bank with $3 million in cash, McCauley received another e-mail from Cook telling him to immediately FedEx all his files to the new business manager. McCauley replied that he was working on it. “Thanks, brother,” Cook wrote. “You’re very welcome,” McCauley shot back.

Forty-eight hours later, McCauley and his wife boarded an L.A.-bound train, and at 4 a.m. stepped off the Amtrak platform in Toledo, Ohio, hopped into a rental car, and disappeared for eight days. Prosecutors say that during that time they visited Las Vegas and also rented a storage facility. All the while, they say, McCauley’s 16-year-old son had no idea where his parents were or what they were doing. Two days into the sojourn, McCauley’s son sent his father a text message: “Luv u 2 but I wish u would call Dane it’s really stressing me out that ur blocking every1 out.”

With McCauley suddenly out of contact, Cook went to Shadduck, his money manager, and they began to review the accounts. That’s when they discovered the $3 million check written to Darryl McCauley. Cook called the authorities. On December 30, McCauley, who had since returned to Wilmington, was arrested.

Prosecutors say police found $30,000 when they searched McCauley’s home, and another $800,000 stuffed into a wall safe in a condo he owned in York Beach, Maine. In the months that followed, prosecutors laid out a case detailing nearly $11 million in thefts dating back to 2004. They say McCauley repeatedly siphoned money from Cook’s accounts into his own and, in addition to the $800,000 condo he bought in Maine, sank cash into a series of real estate investments including $2.5 million in the Atlantic House, a hotel complex in York Beach; $500,000 in the Blue Sky restaurant in York Beach; and $300,000 in two restaurants in Florida. They claim he also paid off about $1.5 million in personal charges he rang up on an American Express card. Prosecutors say $3 million is still unaccounted for. (McCauley has pleaded not guilty to the 28 counts of larceny and one count of forgery he faces.)

According to court filings, McCauley’s son told the grand jury that in the months before his parents’ brief disappearance, he had once hopped onto his dad’s computer to find out how to break in a baseball glove. When he typed the words “how to” into Google, the page displayed an old search that seemed strange: “how to hide money.”

It took Dane Cook a long time to settle on this house up here on the hill. He lived in the same apartment in L.A. for 11 years, took his time looking for a house that felt just right. When he walked up the stairs here last year, Cook says, he knew right away. It was because of the trees. He’s nicknamed them Mom and Dad. “This is an oak,” he says, showing me around the yard. “That was my mother’s favorite tree.” On the other side of the house is a tall palm tree. “My dad’s favorite place that he ever traveled to after he came back from Korea was San Diego, and he used to tell these stories about how he loved palm trees,” Cook says. “To walk up the stairs and see both of these trees on the same property, I kind of took that as a sign that they loved this place, that they would dig it.”

Cook moved in only six months ago; his brother’s never been here. But he can’t get into that. He can’t say a peep about his brother, not while the case is still pending. He says he’s got the “no-comment cuffs” on. Cook lounges back on a couch on the patio and proceeds slowly through the unfamiliar sieve of self-censorship. This, he says, is the worst thing for a comedian.

“The words that describe it, I gotta be really careful, but it’s betrayal. It’s really a word I never thought I would have [to use] in my life,” he says. He looks right at me, his face sad and angry. “I never thought I’d get caught out here in that kind of stuff. You think, ‘Okay, these people got my back. This is the castle behind me. This is my team, my crew.'”

Cook says he used to pride himself on having a pretty good radar about those he let get close. He was careful, he paid attention. And he knew what it took to straighten things out, no matter what needed straightening out. “That’s the part of my father that I felt like I did become and absorb. He had a great way with people, of dealing with something. ‘Dane, you get up, you go right down there and you talk to that person face to face. You look that man in the eye.’ I became all those things,” he says. “And to sort of have something meet in the middle was so unfathomable.”

I ask him what it was like, that moment on the phone with Shadduck, when he learned what his brother allegedly had been up to. He starts quickly, “Look, man, all I know is that it was like, uh….” Then he pauses. A long pause. Thirteen seconds. The silence allows pain to creep across his face. “I just remember,” he begins again, looking away from me, “how I felt when I heard that my mom was sick, and I didn’t think anything could even come near that.”

Another pause.

“How quickly life can change.”

When his parents were dying, Cook kept working. He’d dash from hospital beds to movie sets to arena shows and back again to the bedside. He says this is what his parents wanted, and they knew it was what he needed.

Now there’s this stuff with his brother, and a sign that Cook is coming out of his tailspin of disbelief is that he’s thinking about how to use it. “I just made my first joke about it,” he says. He was with his sister, Courtney, and it just came out, an authentic funny moment. It might even be the beginning of new material about his brother, because it will be material someday. That’s why he made Isolated Incident. That’s why he became a comedian.

Cook’s always come across as an affable guy laughing at the world—”frat-boy humor” is what a lot of people call it—but that perspective had long been tinged with something darker than we knew. “Before this shit happened with his parents or his brother, don’t think that growing up, for him, there wasn’t a lot of pain or emotional stuff,” Barry Katz, who’s been his manager for 15 years, told me. “There was.”

Take his relationship with his father. George Cook was the affable guy laughing at the world; his son, Dane, was the insecure kid who desperately wanted to be like that. “[My dad] was this Allston-Brighton guy, and he rolled with gangs, and all his stories sounded like myths,” Cook says. “He went to BC, he played every sport, and he just had that real dry/cool Boston sense of humor where it seemed like he was gonna tilt into putting you into a headlock and laughing with you, or knocking you out. That real old-school comedy. A man who could be funny, as opposed to a goof. And then I come along and I’m nothing like my dad.”

When he was a young kid, Cook was phobic, feared other people, and was prone to nervous attacks. “I had this tree on the way to school I called the ‘throw-up tree,'” he says, his voice softening. “I would stop at this tree every day, and I would have these breathing attacks, panic attacks. And if I could make it past the tree, I’d usually make it to school. But normally I was dry-heaving or throwing up at the tree, and then walking home.”

Cook always wanted what his dad had, that ability to walk into a room and effortlessly connect. And although he’s adopted a persona that approaches that now, it’s never really fit. He gets called a frat boy, but Cook, who didn’t go to college, says he’s never been to a frat party; he’s never had a drink, never done a drug. Creating a stage persona let him feel perfectly comfortable in front of 20,000 people. There’s no puke bucket, but when the show is over and it’s time for the meet-and-greet, even now he has that little bit of panic in him, he admits.

At Arlington High, Cook met a drama teacher named Frank Roberts, and it was Roberts who coaxed him into expressing himself. “It was almost as if my own father didn’t know how to help me in those areas, to become more outgoing,” he says. “He was just a ‘throw him in the pool to learn how to swim’ kind of guy.”

There was a night Cook remembers when he was driving down Revere Beach in the rain. He decided right there that he wanted to become an entertainer, and he looked up and told the night sky. “I want the premier package,” Cook said. “I want the big ride. I want the whole thing.”

His father wanted him to go to college, but Cook planned instead to go to school in the comedy clubs. “I don’t want to waste my time and your money,” he told his father. In those days, Cook would sit in his mother’s basement in Arlington scanning the comedy club listings in the Herald and daydreaming about being one of the funniest guys in town. He’d hone his material at Nick’s Comedy Stop, and on his way into town in his old ’78 Lincoln Mark V, he’d glance over at the city lights and get the sense that his goals were staring right at him. “I remember this feeling,” he says, “of wanting to make this city proud of me.”

Cook got famous and rich and all the rest, but one thing that he hasn’t yet gotten is the opportunity to come back here and enjoy the embrace of home. “I find that every time I come back and think this is kinda my World Series moment, or whatever you’d want to call it, there’s always something else that happens in my life that makes coming home feel nostalgic or something. You know?”

On New Year’s Eve, he’ll play a big show at the Garden—just a few days after his brother Darryl is scheduled to stand trial. Sometimes timing sucks. But that’s the big ride, right? Sometimes the best things happen right along with the worst. Cook says he’s never felt sorry for himself when things have gone to crap. “I was on the set with Kevin Costner one day doing Mr. Brooks,” a psychological drama in which Cook delivered an underrated performance as a wannabe serial killer. “My mom was really sick, and I remember him saying, ‘You all right today?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, it’s a tough day.’ And he said, ‘When you take big bites out of the universe, the universe takes big bites out of you.’ I’ve probably said that 100 times since then.”

A massive homecoming gig at the Garden certainly counts as a big cosmic bite. Maybe a capstone to a forgettable year, as well. That’s what Cook hopes, at least. “It’s the closing of a book, and I’m starting a new one.” When he says this, I cringe, the same way I cringed when I heard him say, on the making-of DVD that comes with Isolated Incident, that “if this set works out, what I’m going to need to do is get some more parents to die around me.”

I ask him how he can say such things—isn’t he at least a little afraid of tempting more misfortune? And for the first time in our two-hour conversation, he lets out a big, authentic laugh. “I’m not scared. I’m rarely scared.”