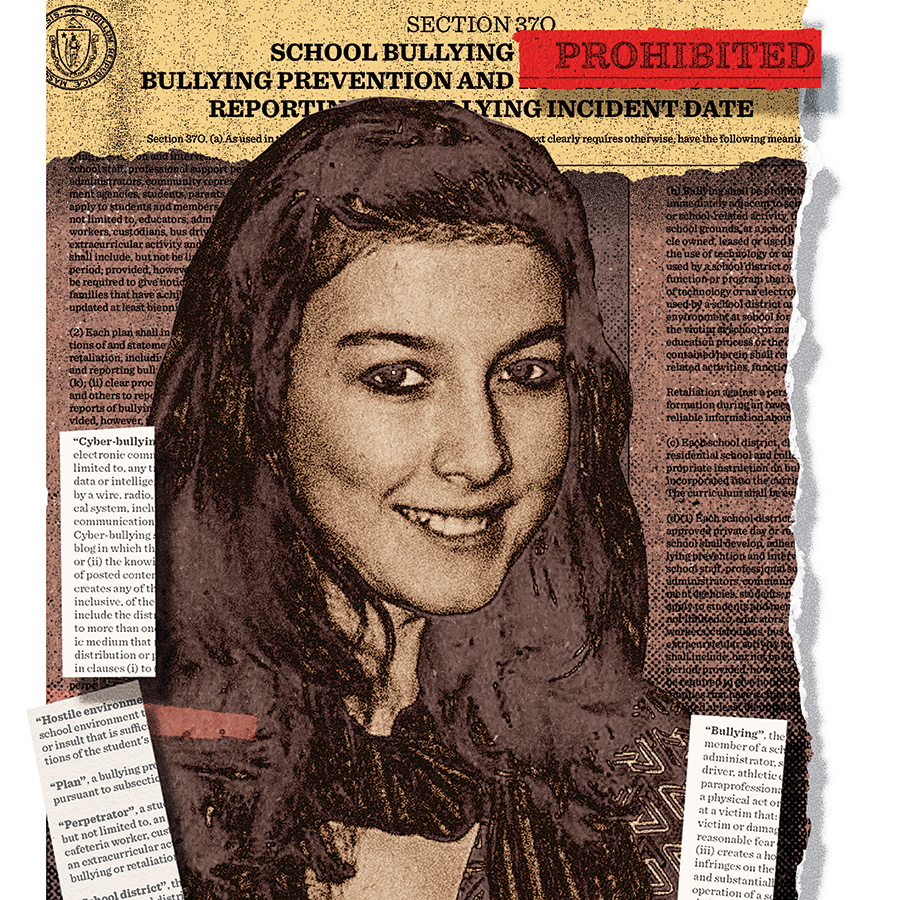

The Tragic, Enduring Legacy of Phoebe Prince

Her death after being bullied at school was supposed to change everything. Now, 10 years later, has being a teenager in Massachusetts gotten any better?

Photo illustration by Benjamen Purvis

Sascha is a 14-year-old ninth grader at Needham High School. She plays volleyball for the freshman team and ballroom dances competitively. She loves history and math. She has long, highlighted hair, braces, and more than 1,000 followers on Instagram.

In early summer, Sascha (not her real name) received a text message from a boy she knew. There were no words, just a photo of a family-size bag of what many people at school knew was her favorite candy—peanut butter M & Ms—pictured on a doorstep she recognized as her own. Sascha opened her family’s front door to find the bag. Only instead of M & Ms inside, the plastic pouch contained a mishmash of candy, dirt, and grass, stepped on and clearly not for eating.

Sascha’s mother calmly asked for her daughter’s phone and dialed the boy directly: “This is Sascha’s mom,” she told him. “I’m giving you one hour to come and pick up your trash from my property or I’m going to your parents or the police.” The trash disappeared, but a few hours later the texts to Sascha resumed, calling her a tattletale, among other things. She doesn’t know why he chose her; she says she didn’t want to ask.

Months later, at the start of the school year, Sascha and the boy ended up in three classes together. It wasn’t long before he started bothering her again. She says he made fun of her outfits as they passed in the hall. He sent her a text saying he’d seen a list of “the sluttiest girls” in the school on TikTok, a social media video app, and that she was at the top. (“He did not actually see a TikTok with our names on it,” Sascha says, “he just said he did so he could call us sluts.”) Finally, one day in October during study period, the boy texted Sascha a video he’d secretly taken of her just a few minutes earlier. The caption read, “If I looked like this I would kill myself.”

Sascha didn’t tell her teachers about what the boy was doing, not even the video. She was embarrassed. She didn’t want to give him the satisfaction of a reaction, either—isn’t that exactly what bullies want? The situation practically felt surreal. After all, she says, “Ever since we were young, [school officials] have made a very big thing about no bullying. We have three entire days of orientation dedicated to it where they tell us there’s no tolerance, you’ll be kicked out of your sport, you’ll be suspended.” They also tell kids that if you’re the one who’s bullied, the school will make sure you feel safe.

Sascha didn’t feel safe, so she told her mom, who emailed Needham High School principal Aaron Sicotte that night. “I forwarded him the texts and I told him that this fits the definition of bullying,” says Sascha’s mom, who was particularly attuned to the situation because Sascha had previously been bullied in both third and eighth grade, and because her daughter suffers from anxiety that manifests itself in occasional stomachaches. “It’s a repeated act. She’s being targeted. She’s being encouraged to hurt herself.” She received a reply 20 minutes later.

Ten years ago, such a swift response might not have been a given. But everything changed in 2010 when 15-year-old Phoebe Prince hanged herself from a staircase in her family’s South Hadley home after enduring a months-long campaign of vicious, coordinated bullying. In early spring of that year, I spent several months reporting for this magazine about the case, which divided a town and affected dozens of families, many of whom shared with me their confusion and fears, their frustration and sadness. I attended school assemblies, school-board meetings, press conferences, and Prince family fundraisers; I dug through mounds of court records, knocked on countless doors, and, one night, rode along with a TV news crew reporting on the story of her suicide as it broke. For months, South Hadley was ground zero for statewide and national discussions about bullying. In what some viewed as a calculated political move and others as a long-overdue call to action, then-Northwestern District Attorney Elizabeth Scheibel pushed legislators to act so that nothing similar would happen again. At the very least, she wanted students and school employees to be extremely clear about the difference between so-called normal teen meanness and criminal harassment with potentially deadly consequences.

Lawmakers rose to the challenge. By May 2010, Governor Deval Patrick had signed the Massachusetts Anti-Bullying Law, at the time the country’s most comprehensive. The new law defined bullying as repeated action that causes physical or emotional harm, places the victim in fear, infringes on his or her rights, creates a hostile environment, or otherwise disrupts the education process, and included written, verbal, electronic, or physical acts or gestures, both on school grounds and off. It legally required school staff to attend annual trainings on prevention and intervention and to report incidents of bullying when they become aware of them. Administrators were also required to make bullying prevention part of the curriculum (such as the “designated” days Sascha mentioned). In 2014, the laws were strengthened, requiring schools to submit annual reports of bullying to the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) and to implement prevention plans in recognition that LGBTQ+ students and students of color are more likely to be targeted.

Well intentioned, the law set out to distinguish bullying from everyday fighting and to establish consequences, but it was broad, and 10 years later, it remains so. Critics contend it leaves gray areas that should be far more black-and-white, and has proven difficult to enforce—or, depending on how you look at it, a little too easy not to. Because while numbers from the Massachusetts education department’s June 2019 Bullying Data Collection Annual Report show that bullying is going down—from 2,245 reported incidents statewide in 2014 to 2015 to 1,935 in 2017 to 2018, even as the number of districts reporting that data grew—there’s good reason to think that many incidents go unreported, both by victims and by schools. “If you want to know how much actual bullying is happening,” says Elizabeth Englander, the founder and executive director of the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Center at Bridgewater State University, which provides anti-bullying training to thousands of schools, “there’s only one way to find that out, and that’s to anonymously survey students.” One reason schools don’t do it, she suggests: They expect they won’t like what they find.

Phoebe Prince was the new girl in town; she had just moved to South Hadley from Ireland with her mother and younger sister at the start of the school year. She was pretty and funny and charming and vulnerable. For a while, life was okay. She started dating an older boy, a popular football player named Sean Mulveyhill. It didn’t take long, though, for Mulveyhill to reunite with his on-again, off-again girlfriend, and that’s when the bullying began. The couple—and several of their friends—set out to punish Prince, daily, for her mistake of getting involved with another girl’s guy, and for having the nerve to think she could be “one of them,” even for a few weeks. For months, students mercilessly tormented and physically threatened Prince in school and online—calling her names such as “stupid bitch” and “Irish slut”; shoving her in the hallways; chasing her, crying, into classrooms—without much intervention from school staff or from fellow students. When she walked home after school one day and killed herself using the scarf her sister had given her for Christmas a few weeks earlier, her death landed on the town like a bomb.

Incredibly, the bullying didn’t stop there: Six days after her death, a “We Murdered Phoebe Prince” page appeared on Facebook, quickly amassing comments suggesting she’d deserved it, and making the culture of bullying that had emerged in South Hadley all but impossible to ignore. It also shone a light on the primary question at hand: Whose fault was it? In a landmark case that divided the town, the district attorney charged six students—two boys and four girls, ages 16 to 18—in connection with the bullying Prince endured. These included crimes such as statutory rape, violation of civil rights with bodily injury, harassment, stalking, and disturbing a school assembly. Five of the students were sentenced to community service on harassment or civil rights charges (with the case against one student dropped). This included Mulveyhill, who in 2019 was accused of rape by a student at Mount Holyoke College, where he was working as a campus bartender. (Mulveyhill has been ordered to stay away from the student, but has not been criminally charged.) No adults were charged in the Prince case, but some faced consequences: The South Hadley superintendent and the high school principal retired the following year; school committee chairman Ed Boisselle stepped down; and in late 2010, the Prince family settled a lawsuit against the school district for $225,000.

Looking back, so much of what happened to Prince is hard to believe, even though I was there. Not necessarily that kids could be so cruel—and, given the volume of traceable material so many of them posted online later, so foolish—but that they could have been allowed to be so cruel for so long, and in an educational setting, no less. It was clear that something was amiss with how the adults at South Hadley High School had chosen to address—or not address—student conflict. At the time, social media was a rapidly emerging force in teenage interaction, and one of the biggest challenges for schools was monitoring what was going on online among their students.

But this new frontier in communications also allowed for one of their biggest excuses: What happened online, away from school grounds, was not their problem. Only it was. While elements of teen meanness and mob mentality certainly existed when I was growing up—teenage girls, especially, can be pretty awful to one another, and I remember refusing to be friends with one girl simply because she dared to date a boy after I did—most of what went on between kids at school stayed at school. These days, though, social media amplifies the effects of bullying, bringing it off campus and into victims’ homes.

In South Hadley, many residents say the town hasn’t been the same since Prince’s death, even as they’ve tried their best to put it behind them. “My generation in this town will never forget what happened to Phoebe,” says Mitch Brouillard, a South Hadley High School parent at the time of Prince’s death who was part of a committee working to enact changes to the school’s bullying policy. His own daughter had been tormented by at least one of the same kids who’d targeted Prince and no one, he believed, had been held accountable. Even 10 years later, Brouillard says “it’s still painful.” Darby O’Brien, who was known throughout the case as a friend of the Prince family and whose youngest son is now a senior at South Hadley High, talks of enduring animosity. In 2012, after O’Brien was thanked in a book about Prince’s death that had been “authorized” by her family, he walked over to his car after work one day to find a brick had been thrown through the windshield. Neither Brouillard nor O’Brien knows what procedures are currently in place at the high school; administrators at South Hadley Public Schools did not respond to requests for comment.

While the town still struggles to fully recover, many believe the tragedy at least led to some positive change. The Prince case, Englander says, “galvanized a lot of people to take action. One of the major goals of the 2010 law was to raise awareness, and it succeeded. I don’t go to any school anymore where people say to me, ‘Well, we don’t have a problem here.’” Still, there has been a lot of confusion. After Prince’s death, “We were flooded by parents who were concerned that their student’s situation could end up in another suicide,” says Jodie Elgee, the principal of Succeed Boston, a counseling and intervention center run by Boston Public Schools that was set up to counsel kids who bully. “The work we did for a very long time was educating parents, students, and staff to help them understand the difference between conflict and bullying.” If a student reports something—whether or not it fits the legal definition of bullying—it has to be investigated.

As a result, says Needham High School assistant principal Alison Coubrough-Argentieri, the number of potential bullying and harassment investigations at the school has increased substantially over the past few years, even as most don’t turn out to be classified as reportable offenses. “I think [the reason for that is] two-fold,” she says. “We’re talking more than ever about issues of race, gender, and sexual orientation. So the students are more aware of their own experiences and their own rights, and the way in which others are interacting with them. Second, we’re more aware as a staff, so we’ll get reports from teachers like, ‘I don’t know what this is, but could you look into it?’”

At the same time, the ways schools have attempted to get bullying under control in the wake of Prince’s death have been wildly inconsistent as they struggle to figure out what works best. Many have put a focus on student-run programs in an effort to try to keep administrators from having to play mediator in every last hallway drama, while also helping to foster an environment in which students feel safe coming forward. At Lincoln-Sudbury Regional High School, such programs range from role-playing to mediation to several groups designed to help students identify and address conflict, or worse, among their friends. The Mentors in Violence Prevention program, started in 2014, teaches students to play an active role in reducing violence and abuse within student relationships, and a confidential peer mediator program made up of about 25 students across all grades boasts a dedicated “mediation room” in the center of the school building. On a recent Friday morning, L-S students in all grades gathered for an assembly featuring a staged reading of the play Good Kids, inspired by the 2012 Steubenville, Ohio, rape case and a panel discussion about toxic gender roles and the importance of intervening to help prevent abusive incidents. “If I wasn’t in the program,” says senior Jake Simon, “it would be very hard for me to know, or know what to do, if I was in an unhealthy relationship or if a friend was, but the program really pushes you to be that person.”

More than 100 middle and high schools across the state, meanwhile, have implemented the Anti-Defamation League’s World of Difference peer-to-peer program, which strives to eliminate the need for students to report incidents to adults and to empower them to facilitate positive change in their schools, says program director Phil Fogelman. He adds that while schools have become much more proactive in recent years, many don’t implement the program until after an incident has already occurred.

Over time, it’s also becoming apparent how these programs are falling short. For all of its great work, L-S has not been without controversy, including an incident last year in which a former student claimed she was sexually assaulted in 2013 by two other students and that the school failed to investigate the event or punish her assailants. It illustrates what is perhaps the biggest issue at hand: Even with stringent laws, how and whether incidents are addressed remains largely at the discretion of the individual schools—or more specifically, the administrators in charge—leaving plenty of potential cracks to slip through, especially since adults and kids rarely agree on what’s “reportable” bullying and what’s something closer to the casual, impersonal sort of teen cruelty most adults remember from their own childhoods. Ten years ago, at the time of the Prince case, South Hadley High School had a no-tolerance policy, with disciplinary consequences that included expulsion. But it was up to the principal to determine what constituted bullying, and whether and how to punish students for it. And despite the legal protections now in place, one problem is that the system is pretty much still the same today.

The ways schools have attempted to get bullying under control in the wake of Prince’s death have been wildly inconsistent as they struggle to figure out what works best.

One aspect of bullying that is changing: what kids bully each other about. Before 2016, Englander says, the majority of students bullied others for social reasons, which included things such as conflict over a boy or a girl or low social status. All of that changed in 2016, when there was a dramatic surge in kids being bullied exclusively because of their membership in a group—such as being LGBTQ+ or having parents who were immigrants. “To my mind, it’s the most serious and disturbing change we’ve ever seen,” Englander says. “It’s fair to say that adults feel empowered to express bias attitudes, and that kids follow their lead shouldn’t surprise anybody. But in all my years of researching, I’ve never seen anything quite like it.”

Even at Lincoln-Sudbury, with its raft of anti-bullying programming aimed at making students feel safe, senior Kares Mack calls the climate “racially charged” at times. “I’ve dealt with people making fun of my skin color, or my hair, or calling me out on the way that I speak,” he says. “I haven’t really been able to talk to anyone about it, not only because of the fact that there aren’t that many faculty members of color at L-S, but because I feel that no one really understands my situation.” Casey Monteiro, an 18-year-old senior at the school, thinks most of the bullying among the 1,500 students happens over sexual identity. “I’m actually writing an essay on this in my English class,” she says. “I’m straight and have never had any issues regarding people treating me differently due to sexual identity, but I know that’s not the case for everyone.”

Of course, it’s hard to fix a problem when we still don’t even know the scope of it. DESE spokesperson Jacqueline Reis says that while districts are required by law to report every incident of bullying—even “alleged” incidents that may not rise to the level of bullying—it’s something of an honor system. Other than when a parent or someone else files a complaint with the DESE claiming a school isn’t following anti-bullying protocol or did not report an incident, no one tracks whether schools are reporting accurate numbers and there are no provisions in place to hold schools accountable. Meanwhile, schools are cautious about being too quick to label kids as bullies, understanding that all students need to be supported, especially as they learn to navigate the social media landscape and the often complex dynamics of being a teen. “The numbers we have are the numbers districts send us,” Reis says, “but we’re not there in their schools.” If the DESE does receive a complaint, it will investigate, but if the complaint proves valid, “there’s no fine or penalty of that nature,” Reis says. This might help explain why a recent survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that, despite official numbers, as many as 14,000 kids in Massachusetts claimed they were bullied in the 2017 to 2018 school year.

In Needham, which in 2017 to 2018 reported just five cases of bullying across the entire town, Sascha’s situation as she describes it satisfies several of the definitions of bullying as outlined in her high school’s student handbook: the repeated use of actions that may include “oral or written threats; teasing; putdowns; name calling; stalking; threatening looks, gestures, or actions; cruel rumors; false accusations; and social isolation,” behavior that “causes physical or emotional harm to the target…and creates a hostile environment at school for the target.” Sascha and her mom say school officials told them that her bully was disciplined, but they do not know how or to what extent beyond the fact that administrators said they “addressed the behavior with the aggressor and applied school consequences.” (He will also be required to complete a Behavior Intervention Program through Needham Youth Services.)

Sascha says she never received an apology. She was told to avoid the boy, though he remains in three of her classes, including two in which he is assigned a seat near hers. Coubrough-Argentieri, the assistant principal, can’t comment specifically on Sascha’s case, but says, “There are a lot of factors that go into a decision about changing a student’s class. It’s not always something we can accommodate. We have to have justification on our end. We certainly have done it and we can. But we don’t always, and that’s where the sort of individual approach to the situation comes up.”

Aaron Sicotte, the Needham High principal, won’t comment on any particular case involving a student. “However,” he writes by email, “the Needham Public Schools have well-defined and thoughtful policies and procedures to investigate allegations of bullying, and we take appropriate and swift action to prevent a future occurrence and support our students…. We strongly believe in helping our students learn from each situation—including mistakes they make—all while maintaining a safe learning environment for each one of our students.”

The circumstances under which an incident is reported to the DESE, meanwhile, are both clear and frustratingly vague. “The question to answer is whether a student has taken part in behaviors that qualify as bullying,” Sicotte writes. “To determine that, we follow our procedures which have a consistent set of steps and, in the end, lead us through specific questions about the incident so we can determine if bullying occurred regardless of the particulars of the situation. In some cases, bullying has not occurred, but the behavior still violates our student handbook, and we put in place appropriate disciplinary action and interventions.”

It’s easy to see why the numbers don’t add up, and why parents and students remain confused. South Hadley parent Darby O’Brien, for one, isn’t surprised. He’s seen this sort of thing before. While he says his son feels safe in Phoebe Prince’s former high school, he still believes that “institutions will protect the connected and they will protect the institution. That’s sure as hell what happened here. They were looking out for themselves. I’m not naive enough to believe that’s changed.”