The Highly Competitive, Hypocritical, and Altogether Essential World of Pandemic Pods

During the most stressful school year on record, learning bubbles are the one thing saving working parents’ sanity—so long as no one dares to break the rules.

Photos via Westend61/Leander Baerenz/Getty Images / Illustration by Benjamen Purvis

On a Thursday afternoon in mid-March last year, Elizabeth (last name withheld upon request) sauntered out of her Arlington home and down her walkway toward Jaime Viteri’s idling Highlander with a glass tumbler in her hand. The neighbors and close friends had decided to drive to school pickup together after a single text message from their district’s superintendent upended their lives: Schools would be closing for the next two weeks in response to the coronavirus. Like so many working parents across the state, both Elizabeth and Viteri depended on public school and afterschool care to be able to do their jobs. Now what were they supposed to do? Elizabeth climbed into Viteri’s SUV, shut the door behind her, and passed the tumbler to her friend. “We’re going to need this,” she said. The glass held tequila in it.

There was no time to panic. They needed a plan and they needed one now. Before embarking on the five-minute drive to Thompson elementary, Viteri downed the shot as Elizabeth shared, rapid-fire, information that a friend of hers in Sacramento had cobbled together in the face of her district’s recent school closure. “It’s called a pod,” Elizabeth said, explaining how it was intended to keep their kids safely educated and socializing, their careers on track, and the whole family’s sanity in check during what experts thought would be a short but disruptive period. Viteri, a professional project manager, listened intently during the short drive to school, then quickly laid out a clear strategy for how they would form a pod themselves.

The pair rolled into the school’s parking lot, and descended from the SUV into a sea of bewildered suburban humanity. Young kids were running around the schoolyard, buzzing with excitement at the unexpected news of school being canceled for two weeks, while parents stood commiserating in clusters and trying to reassure each other: It will just be two weeks, right?

Viteri and Elizabeth felt a wave of pride. They were way ahead of the game with their planned pod. Now they just needed to find themselves a pod supervisor. Already, they sensed that—like so much of suburban life—podding was about to become a competitive blood sport. So when Viteri’s daughter begged her mom to ask her favorite afterschool teacher to babysit, a light bulb went off. Viteri hired her on the spot to care for her and Elizabeth’s four children, later agreeing to pay her $30 an hour.

Over the next three days, they and their husbands hammered out the details of how their pod would work, including COVID-prevention measures and rules, and then cemented the arrangement with a handshake. The plan was as much about social engagement as it was about schooling—for all involved. “This was a lot more than anyone else had figured out by March 15,” Elizabeth says. “By establishing a pod, our kids had each other to hang out with and the adults had much-needed socialization with other adults, all while following COVID protocols.”

While many families scrambled and struggled during the early throes of the pandemic, Viteri’s and Elizabeth’s families never skipped a beat. By the time Monday rolled around, their kids were supervised and learning, while all four parents were busy at work without worry or interruption. “This pod was saving our sanity,” Elizabeth says.

Just as Viteri and Elizabeth suspected, other parents weren’t far behind. As two weeks stretched into an indefinite period of remote learning, more and more parents around the Boston area formed pods. By the time late summer rolled around and school districts announced they were starting the year either entirely remotely or with hybrid programs, mixing remote and in-person learning, the podding craze had hit a fever pitch. Parents took to Facebook groups seeking other parents to pod with, and scoured the Internet for teachers and tutors to supervise them. At least two Massachusetts Facebook groups were formed to help parents form pods—a smaller one with 2,500 members and another, called Massachusetts Parents Seeking Pods, Teachers and Tutors, that soon had a following of 8,000.

Competition for teachers was fierce. Parents spent hours on the Facebook page, hitting refresh over and over in hopes of being the first one to see a new post from a teacher announcing their availability. Parents offered teachers signing bonuses, paid vacations, sick days, exorbitant salaries, and the guarantee of fewer students than some other pods looking for teachers—which would mean less work and fewer health risks for the teacher, but more expense for each of the parents—in order to lure the most qualified educators away from other offers. By the fall, a MassInc poll found that nearly one out of five parents of kindergarteners through fourth graders in the state had formed a pod.

For families lucky enough to find a good teacher and other parents to pod up with, these arrangements have been nothing short of a lifeline. They have helped ensure that the careers of working parents (especially moms, who have taken on the lion’s share of childcare responsibilities during the pandemic) were not derailed by remote schooling in a metro area where few can afford the luxury of a one-income household. They’ve also saved children—and their parents—from social isolation, and ensured that legions of kids didn’t fall too far behind in their schoolwork.

Still, pod life isn’t all good grades and living by the golden rule. Pods have also been the source of criticism and conflict in the Boston area. They have been at the root of strained relationships in some suburban communities, and criticized for accelerating achievement gaps between the podded and the podless. And they are not nearly as COVID-safe as most pod parents desperately want to believe they are. There is also concern among experts that they may have lasting effects on public education if parents, who have grown enamored of their children’s bespoke education experience, decide not to return to public school and take their funding with them when this is all over. The question, then, isn’t how much pods are costing parents now—it’s what they’re going to cost us all in the future.

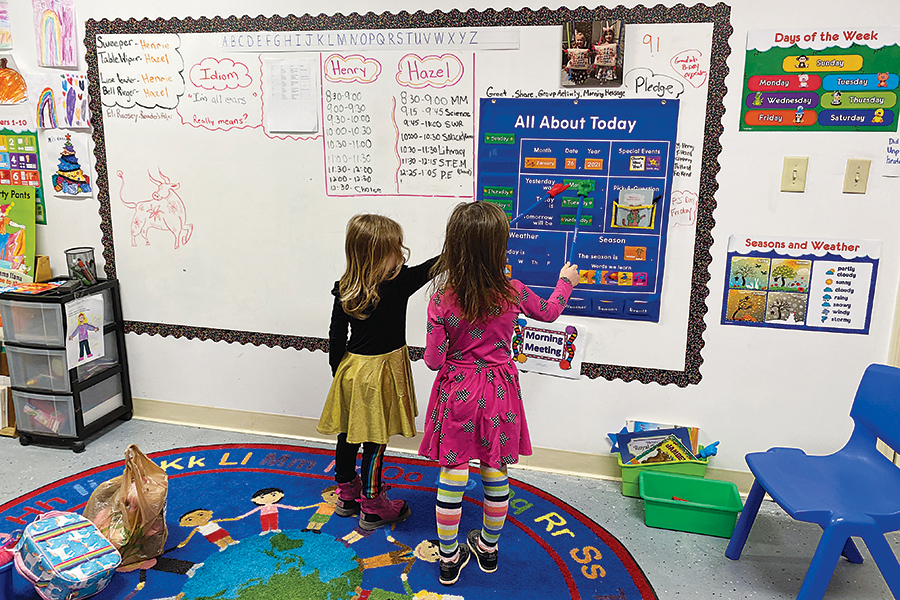

Two local families transformed a former storage room into a makeshift kindergarten classroom for their kids. / Photo by Julie Weissman

Every morning, Emily’s and Robyn’s daughters file into their kindergarten classroom in the suburbs, where the walls are adorned with posters displaying the alphabet, numbers, and sight words. In the corner, there’s a tent in the shape of a castle for quiet time with books. The two girls start each morning with check-in, writing their name in shaky, large, all-capital letters on a slip of paper before dropping it into the attendance box for their teacher. They end each day by gathering in a circle and singing a goodbye song with her.

Just about the only giveaway that this is not a typical public school classroom is the fact that the two girls, who are cousins, are the only two students in the entire classroom, and that for a few hours each day they can be found following their real public school kindergarten teachers—one in Needham and one in Newton—on their iPad screens. (Another giveaway is the fact that the whole classroom, in the former storeroom at Robyn’s home, is painted pink—both girls’ favorite color.) As for the teacher, she is one their parents hired to run their pod and provide the kids with more schooling than the few hours they get remotely from their respective districts. “The teacher helps them with their Zoom classes, but she does a ton of supplemental stuff—she’s amazing,” says Robyn, a busy working mom who gave birth to her third child the week school started. “Having this pod means we are able to function as a household.”

Not all pods work the same way—in fact, when it comes to pandemic pods, there is no one definition. Some parents, like sisters-in-law Robyn and Emily, are related, some are close friends, and some, until they came together to pod, were complete strangers. Pods can be tiny, consisting of only two students, or have as many children as parents are willing to tolerate. Some parents have pulled their kids from school altogether and have turned over their children’s education for the full year to an experienced teacher who shows up each day in person or teaches the pod remotely. Other pods are supervised by a glorified babysitter, or a pod parent on rotation, whose main job is to make sure kids can log on to their remote classes and sit still long enough to learn something. For the most part, pods are for younger children who would be unable to school themselves remotely on their own or whose parents have found their public school’s remote-learning program to be deficient. In some pods, parents sign contracts, vowing not to see anyone for any reason outside of the learning bubble. Others are more laid-back and flexible, so long as parents keep one another apprised of their extra-podular activities.

Regardless of their structure and governing norms, all pods are engineered to accomplish the same feat: Enable parents to keep working and kids to stay academically and socially engaged. No one has benefited from this more than mothers, who have borne the brunt of the economic and professional ravages of the pandemic. Across the nation in September, 1.1 million employees dropped out of the workforce. Fully 80 percent were women, many of them abandoning long-nurtured careers to help their children learn remotely. Alicia Sasser Modestino, director of research at Northeastern University’s Dukakis Center, says that Massachusetts has one of the highest rates of female workforce participation, which also means it is one of the states with the greatest dependence on childcare. A survey she conducted in the fall found that a quarter of the women who became unemployed during the pandemic said a lack of childcare was the sole reason.

For countless other women, pods have been the bulwark against job loss. “If I didn’t join the pod, I probably would have had to take a leave of absence or quit my job,” says a Newton mom who works in pharma and asked to remain anonymous after getting attacked on a Facebook homeschooling group for her decision to hire a teacher and not teach her first-grade son herself. She says she has no regrets about joining a three-family pod: “My son has ADHD, and the computer did not work for him in the spring. He was refusing to go to his kindergarten class online.”

Keeping a job isn’t the only benefit parents have experienced. For those who have podded with family or good friends, it has meant that adults, too, get playdates. “The beautiful part,” says one pod father from a northwest suburb, “is we get to socialize with our friends and spend time together for meals and holidays. That’s an incredible experience for the kids, and also for the adults because it makes us better parents, because we are in emotionally healthier places.”

In fact, what was originally designed as a stopgap measure to prevent kids from falling behind has for many turned into a form of schooling that has surpassed anything they could be getting out of public or even private schools. Retired teacher Renee Gelin is currently working for a two-family pod of four kids, two of whom are hybrid students she supervises and two of whom have withdrawn from public school and are being fully schooled by her. She says one of the hybrid kids may have to repeat the year. With the other two, she explains, “I can take their education any way they want. I can tailor lessons to their interests and their speed. I see them 16 hours a week, and by February we were done with second grade.”

Parents have also found themselves captivated by the kind of education that pod teachers are providing their children. “It’s an actual private education, a customized individual-attention scenario. It’s like the ideal one-room schoolhouse from a long time ago when things were simpler and when you had a very personal relationship with your teacher. Our teacher knows my daughter like the back of her hand,” says Winthrop resident Diana Viens, who works in biotech and founded the Facebook group for teachers and parents to form pods. “All of those beautiful things are what comes to fruition when it all comes together in a pod and it jibes.”

This is not to say, however, that pods always jibe, nor that it’s always smooth sailing in pod world.

It’s not just academics: pods like the Needham one also fend off the social isolation many kids are suffering from during the pandemic. / Photo by Julie Weissman

If pods have been a lifeline, they have also caused their fair share of social upheaval. In the waning days of summer, when school districts throughout the Boston area announced fully remote starts to the year or hybrid programs, parents were in a panic. Countless moms and dads who had gone it alone through the ravages of remote schooling throughout the spring were desperately seeking spots in pods as if they were life rafts flying off the decks of a rapidly sinking ship. Elizabeth, from the Arlington pod, says one mom in town started sending her text messages asking to join their bubble. Her tone became increasingly intense with each missive, to the point the mother was no longer asking, but demanding, to be let into her pod. “I ignored the last few texts from this woman,” Elizabeth says. “Now I have to make quick runs for it when I see her coming my way in town.”

That wasn’t the only way pods tore at the social fabric of communities. When Viteri and Elizabeth first podded up, they were judged harshly for socializing together at a time when many people were avoiding their fellow neighbors. One day, a friend of Viteri’s was at the hairdresser and overheard someone complaining to her stylist about how irresponsible Viteri and Elizabeth were. Once the story got back to her, Viteri could only laugh. “Funny thing was,” she says, “this woman, who was loud and all over my choices, was in public having her hair done!”

By late summer, though, the two working moms noticed that suddenly people who once saw them as the devil were now interested in talking to them all the time. Parents, including ones who had judged Viteri and Elizabeth harshly, saw and understood the urgent need to pod and sought out their help to figure out how to set up their own pods. This gave Viteri a level of power she hadn’t known before—weighing in on which parents were good pod material and which were not, and doling out advice when it came to expectations and rules for designing a successful pod. She shared with parents what questions they should ask of one another and teachers, as well as the best communication strategies to employ. In other words, she held the book of magic spells—and those close to her benefited.

If the scramble to find pod mates caused distress, the scramble to find teachers was no less cutthroat. Desperate times often required desperate measures. One day over the summer, Viteri says, her daughter found their pod teacher leafing through the school directory trying to match up faces with the many families who had been offering to hire her out from under Viteri and Elizabeth. Viteri says the joke was on them: Little did they know, she and Elizabeth were already in the process of hiring a new, more experienced tutor for the fall.

Some parents weren’t satisfied to poach teachers from other pods. In Bedford, the district’s superintendent, Philip Conrad, took parents to task in an email after he learned that some of them were trying to lure away the schools’ teachers to instruct children in pods instead of the students in his district. This came at a time when schools were already having trouble getting enough teachers and substitutes to cover their needs.

Even when a pod has managed to secure a teacher without pissing anyone off and choose members without making enemies in town, maintaining intra-pod relations can prove challenging. In theory, pods are democratic entities with power shared among its members. In reality, the parent who does the organizing, or who hosts the pod in their home, often wields more power and sometimes feels resentment toward the other parents for the added responsibilities, cleanup duties, and expenses involved. When the hosts of a Needham pod gave their teacher the day off during the snowstorm in December, for instance, one member said she was shocked that none of the other parents had been consulted. In another pod in Lexington, one of the six children was making it pretty clear she didn’t want to be there and was disrupting the other kids trying to do their work—leading to a difficult situation for the pod’s host, Olivia Kelley. “It just wasn’t a good fit for her,” Kelley says of the girl. “So her mom and I had a conversation and she left. And it was a bummer.”

Things get even stickier when you consider the whole reason pods exist in the first place: because we are in the midst of a pandemic. Pod members have to agree on the rules members and teachers must follow to prevent the spread of COVID—and then they have to stick to them. Navigating these agreements, and disagreements, isn’t always easy. The teacher in the northwest-suburb pod, for example, was hired after telling the parents that her adult children no longer lived with her. Soon after, however, her kids were back, and behaving recklessly. The teacher was unwilling to demand they do more to prevent transmission, so the parents hosting the pod found another instructor in hopes of replacing her. Their pod mates, however, were not keen on disrupting the kids’ schooling by switching teachers midyear, leading to a conflict that was ultimately impossible to overcome. “When there is a third party that is arranging and facilitating school, then parents have someone else we can all be mad at together,” the dad says. “When you are hosting and facilitating a school yourself, the dynamics are on you.”

So the host parents ultimately decided to leave the pod and are going it on their own now, trying to homeschool their daughters while continuing to work. “We are all still friends and I think we are in a good place, but there were some tough moments for a couple of weeks,” the dad says. “So much energy goes into these things; it can be really difficult. It’s like a mini divorce.”

The questionable compliance in that pod, it turns out, is pretty common. Many pod members don’t wear masks inside their bubble and often see other people outside the pod; their teachers see other people, too. Another issue when it comes to safety, according to Emerson College biologist Jamie Lichtenstein, who researches COVID-19 and has worked on public health responses to it, is ventilation. Our mostly older housing stock in the Boston area has rates of air exchange that are below what is needed to provide an environment safe from transmission and below what is found in most schools, Lichtenstein says, adding, “The reality is that the way most pods are implemented does not meet the safety standards.” In fact, she says, recent research comparing remote students and in-person learners in the same school district—which at press time was still unpublished—found higher rates of COVID-19 transmission among remote learners than in-person students.

Regardless of their posturing, the truth is many pod parents are likely aware of these safety issues on some level. “Pods require accepting some hypocrisy or a false reality that pods are undeniably safe, but this is not real,” says Steve Bordeau, a member of a four-family pod in Needham. His children’s teacher, for instance, leaves each day and goes to lead another group of preschool kids in the afternoon, meaning his pod is exposed to an exponentially greater group of individuals beyond the confines of their bubble. “This is a major concern that we all silently agree to overlook.”

This tacit agreement to overlook questionable behavior—and even interpersonal conflicts between kids or adults—is in some ways completely understandable. After all, the consequence of being kicked out of a pod, or quitting, is nothing less than putting your career, your family’s finances, and your child’s education and emotional well-being at risk. So you suck it up and settle for what you have. You do what you have to do to ensure that you don’t get kicked off Pod Island, not now, not ever.

With the children in a four-family Needham pod busy doing schoolwork under the watchful eye of their pod teacher, their parents are able to do their works, too. / Photo by Julie Weissman

When the pandemic is over, will pods be, too? Education experts aren’t so sure. And that’s leading to a lot of anxiety about the future of schoolchildren across the state.

The biggest concern about pods is that they—like many other aspects of the pandemic—are widening achievement gaps between kids from affluent and low-income families. The Bedford superintendent who was incensed over parents’ attempts to poach his teachers, for example, referred to learning pods as “privilege pods” in his email. He may have been the only superintendent to openly criticize the arrangement, but Michael Horn, who focuses on education at the Christensen Institute, a Lexington think tank, says he’s not alone. “From the conversations I’ve had, I would say, districts have sort of treated pods like they treat Russian Math, which is to say, ‘We know students are doing it, but we don’t like that they’re doing it. We wish that they would just follow our program.’”

Education experts aren’t the only ones concerned about equity—or a lack thereof—when it comes to pods. Pod parents, too, struggle quietly, even agonize, over their decision to pod, knowing how many families would never be able to afford to hire a teacher. “We know that we are part of the problem,” admits Emily, of the two-family Needham pod.

Pods may not be an entirely affluent phenomenon, however—at least not in some of their incarnations. For generations, low-income families have banded together to share resources in the face of adversity. “White people did not just discover pods,” says Keri Rodrigues, cofounder and president of the National Parents Union, herself a pod parent in Somerville. “For them, it is an adorable new bougie name for the way underserved poor Black and brown folks have survived forever.” In fact, MassInc poll data reveals that there is little variation by race, ethnicity, or income among parents who are podding in the state.

Still, there is a difference between pods in which parents supervise kids while they attend a remote schooling program and those in which parents spend $25,000 to essentially have a governess for the year. Steve Koczela, president of the MassInc Polling Group, says the data doesn’t capture these distinctions. Nor does the poll account for other variables that could have affected the results, he says, such as affluent parents who responded that they aren’t podding but may have their kid enrolled in a private school where the child still attends in person.

Beyond individual student performance, there are also looming concerns about what effect pods might have on public schooling in general and how we think about school-choice options within the state. Up until now, the school-choice debate was largely confined to urban areas and focused on charter schools. Suburban parents, meanwhile, mostly opted to supplement their children’s public school education with extras such as Russian Math and other enrichment programs. The experience of being in a pod may change that calculation for many of them. “I think some parents won’t necessarily want to revert to the status quo ante when this is all over,” says Paul Reville, former state secretary of education and a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. And defecting en masse for more permanent micro-school arrangements, he notes, could pose an existential threat to public school systems as we know them because as students pull out, funding disappears.

Almost all of the parents interviewed for this article, however, said they didn’t see their pods as a permanent path for their children’s education, even as they raved about how amazing it has been for their kids. Cortney Eldridge, a pod parent in Belmont, hopes that the lasting effect of pods is one in which parents continue to help one another care for their kids in the post-pandemic era—including rotating who walks a group of neighborhood students to school each day at an hour when many parents already have to be at the office. But she doesn’t see them as disrupting public education—at least not in her family. Even as she speaks in an awe-tinged tone of the beauty of witnessing the imagination and creativity of her kids and their pod mates these past few months, she has no doubt that her kids will return to public school once everyone is vaccinated.

“I love my children,” Eldridge says, “but get them out of my house.”