The Art of Medicine

One rainy night in early fall, a small group of first-year residents at Brigham and Women’s Hospital took a few hours out of their exhaustingly hectic routines to visit the Museum of Fine Arts. The field trip is mandatory, part of a “ Humanistic Curriculum” the hospital runs in an effort to turn out more reflective, well-rounded physicians. For the young doctors, the night at the museum was a moment of respite in the storm of their daily lives—a chance to breathe, look for perspective, and get honest.

Led through the museum by Brooke DiGiovanni Evans, head of gallery learning, the group studied wildly different works of art—from a sculpture by German artist Käthe Kollwitz to a cloudlike installation of Styrofoam cups by Tara Donovan. By the end of the evening, when the doctors gathered around an Etruscan sarcophagus in the Greek Archaic Gallery, they were ready to talk about the hardest thing physicians face—death.

“The strangest part to me, when someone dies in the hospital, is how the giant machine of the hospital just keeps clunking along,” one of them said.

“How do you deal with it? Probably all of your patients die,” another remembered being asked by a Stage 4 cancer patient.

Joel Katz, the hospital’s residency program director, helped develop the program. “Art can take students out of their ‘comfort zone,’” he wrote in a paper discussing its effect on participants. “In the confines of the museum they can escape preconceptions, distance inhibitions, and minimize performance anxiety. Participants can relax, share clinical stories, reflect on professional concerns, and collaborate with one another outside the pressing demands of a busy hospital.”

photograph by christopher Churchill

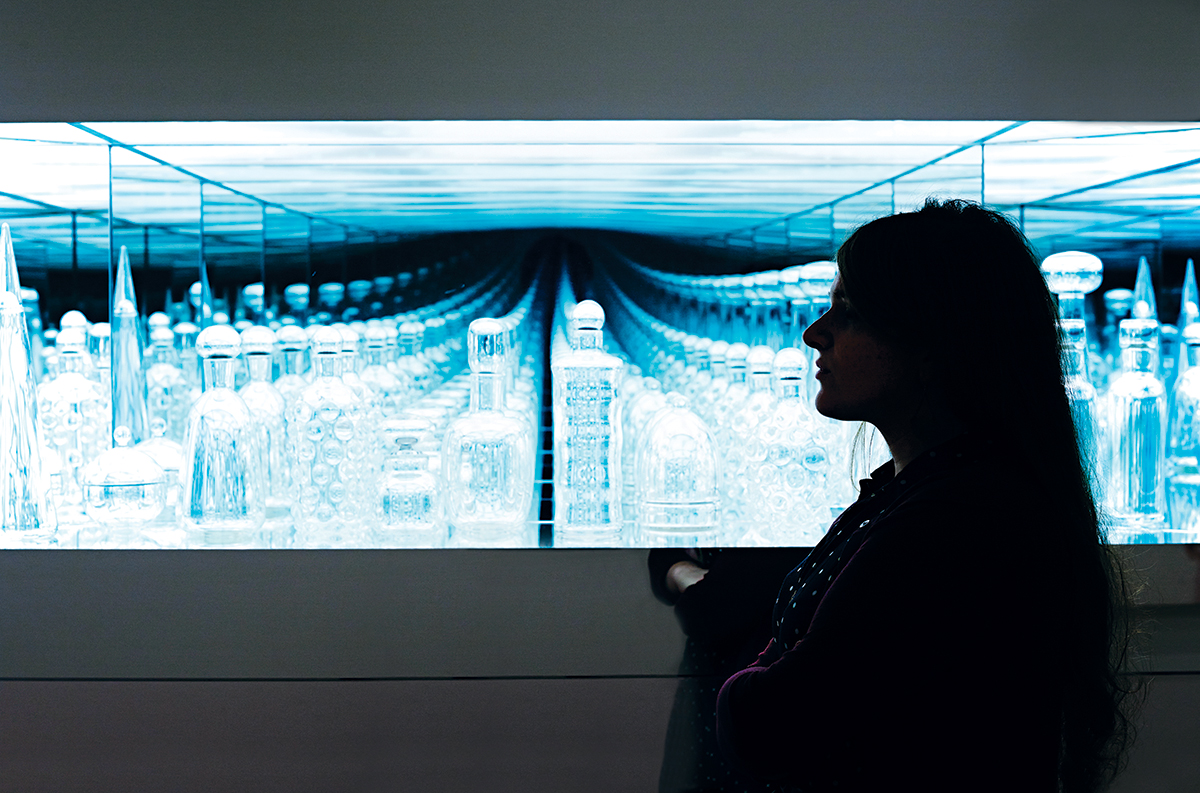

“I grew up in Washington, DC, and this piece looks a lot like Arlington Cemetery, sort of going off into the distance forever. There is also a sense in which there’s something very scientific and laboratory-like about the piece. It looks like a very sterile field. But if I want to be optimistic, it’s a really beautiful piece. It’s a beautiful object to look at. It’s uplifting how amazing it was that someone could make this thing that is so clean and shiny. There is a power to art you can’t deny. It allows people to have a focal point on which to reflect. This [program] gave us time to reflect on those things. It’s a reminder that life is not about extending it at all costs, but appreciating what life creates.”

—Alexandra Charrow, on Endlessly Repeating Twentieth Century Modernism, by Josiah McElheny, 2007

photograph by christopher Churchill

“When I saw this statue, I immediately thought of one of my oncology patients, actually. This particular patient’s spouse, he was always present, from the first time I met them until the last time I saw them. He quit his job, pretty much dedicated his life to being at her bedside. He was just as much a part of the patient’s room as she was. He was always there. I realized physicianhood involves a lot more than just caring for the patient, and the medicine, and the numbers, and the labs and imaging. It’s about being there. It’s just about being present, a lot of the time. And not just taking care of the patient but taking care of the patient’s loved ones and the people the patient cares about. Seeing the statue and seeing how the male figure was supporting the female, ill figure really brought home to me that her spouse was more important than any member of the medical team.”

—Sunny Varshney, on The Lovers, by Käthe Kollwitz, 1913

photograph by christopher Churchill

“I was reflecting on how peaceful and serene their creation was, that they had prepared their whole life for their death. It made me think about how these people had prepared for their death and left this beautiful piece of art in their memory, and about all the deaths I had witnessed. Some of the most memorable deaths have been people who have been able to prepare and have family members at their side. Coming here was a reprieve for me, to reflect after a very busy last few months, and to discuss it with everyone going through the same thing. There are battle scenes surrounding the image of two people who are very peacefully together for all eternity. It invoked the battle we fight for the patient, to bring people to this very peaceful end of life.”

—Molly Plovanich, on Sarcophagus and Lid with Husband and Wife, Etruscan, artist unknown, 350–300 B.C.