Researchers Are Using Origami to Study Human Tissue Engineering

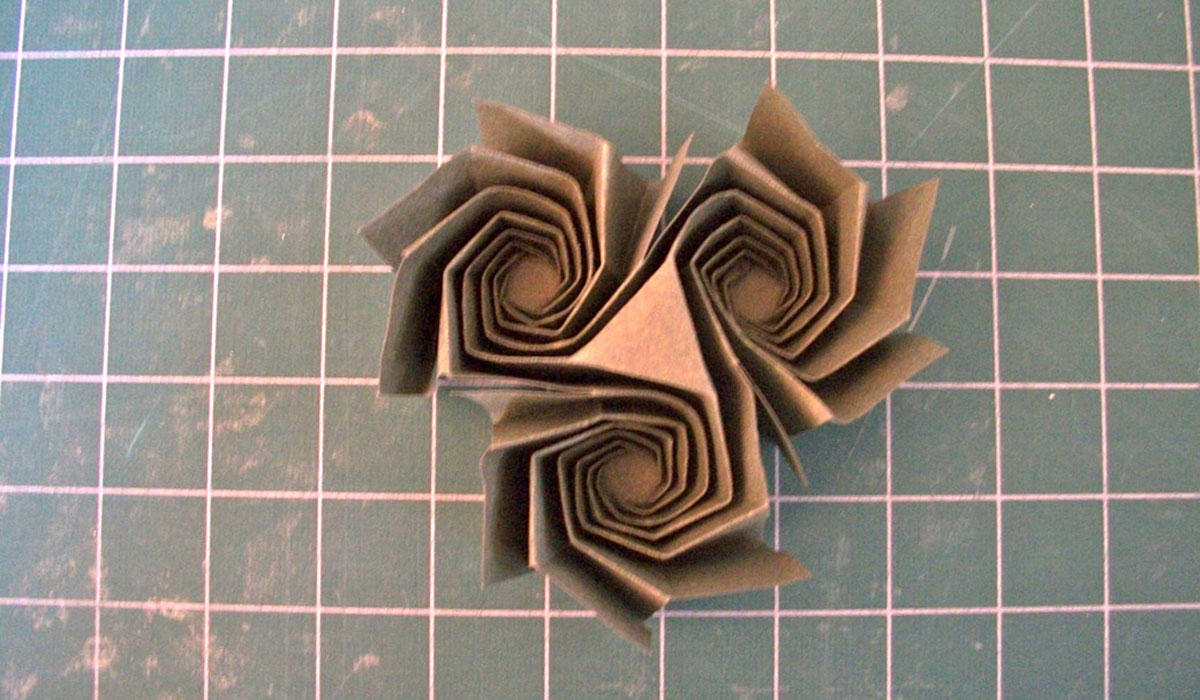

an origami structure created by Livermore’s team. photo provided to bostonmagazine.com.

For those who are suffering from disease or traumatic injuries, receiving an organ transplant can be the difference between life and death. But the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reports that each year more than 7,600 lose their lives while waiting for the surgery.

“It’s a big problem. The supply of organs is nowhere near as large as the number of people who would benefit from receiving them,” says Carol Livermore, an associate professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern. “Wouldn’t it be better if [we] could grow you a new organ from your own cells? It could be made to order and, because it’s from own cells, you wouldn’t reject it.”

That’s why Livermore is leading a team of researchers to study the complex process of tissue engineering using origami, the Japanese art of folding paper into various shapes and structures. Tissue engineering involves the use of human cells to produce new tissue or organs that can be implanted in the body. Livermore says that the existing ways of engineering tissue are problematic because the cells often fall out of alignment when converted from 2-D to 3-D forms. The cells need to be aligned properly in order to create the right tissue features, she says. This is where origami, which relies on folding a 2-D material (the paper) to create an intact 3-D structure, becomes useful.

“In general what you’re trying to achieve is some kind of 3-D structure, and [that’s what] origami turns flat things into,” Livermore says. “You could imagine that there’s broad applicability of origami for making 3-D tissues, but more specifically tissue types that have a layered structure.”

Origami’s conduciveness to layered structures is what prompted Livermore and her team—origami expert Robert J. Lang, mathematician Roger Alperin, and MIT professors Sangeeta Bhatia and Martin Culpepper—to investigate its applicability to engineering liver tissue. Livermore says that the liver is made up of small units known as liver modules, which are stacked to form the organ. Her team’s focus on this area of human anatomy seems especially relevant here in the Commonwealth where, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, more than 650 people are waiting for liver transplants—more than the number of people waiting for pancreas, heart, lung, and intestine transplants combined.

Although the use of origami in tissue engineering seems farfetched, Livermore says the ancient art form is becoming increasingly popular in various areas of scientific research. The National Science Foundation, which is backing Livermore’s research with a $2 million grant, is also funding an investigation of the use of origami in designing surgical instruments.