Social Skills Are Built with Legos at Franciscan Children’s

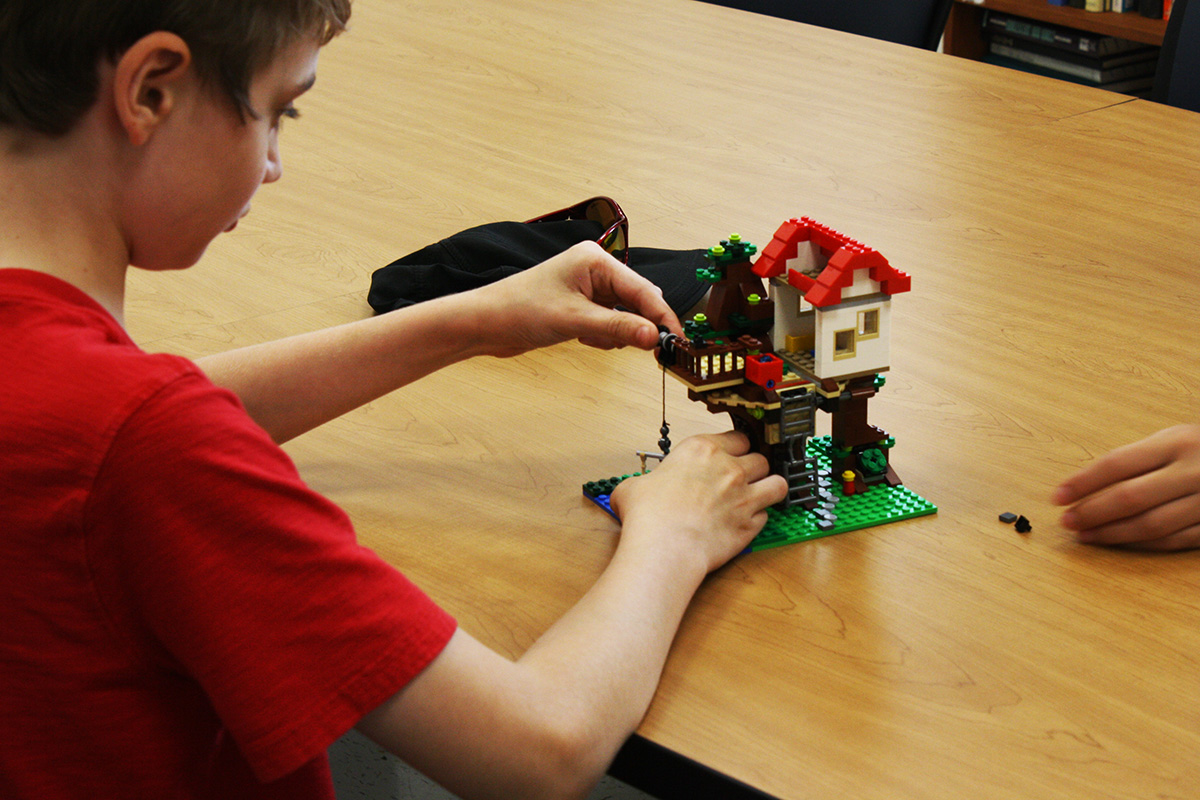

Blake works on the treehouse/Photo by Jamie Ducharme

Lego structures line the windowsills of a spacious conference room at Franciscan Children’s. There’s a race car, a fire-breathing dinosaur, and a helicopter, all elaborate and all perfectly assembled. But these creations aren’t the work of idle hands—they’re therapy.

This spring, Franciscan added Lego Club to its autism treatment portfolio. Spearheaded by clinical psychologist Shoshana Fagen, the group uses the beloved toys to help children on the autism spectrum develop communication, collaboration, and social skills.

“Kids love Legos, and the best way to get a child to engage in learning a new skill is using something that they enjoy doing,” Fagen says. “A lot of children on the autism spectrum automatically find themselves gravitating toward things like Legos, because it’s very structured, very clear—when you’re using Legos, there’s no need to have to understand the nuance of a social situation.”

Lego Club is not the haphazard building of your youth. Remember that elementary school activity, in which you describe each step of making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich in painstaking detail? It’s a lot like that, only harder.

At a recent session, two boys, ages 11 and 13, finished a tricked-out treehouse, rotating, along with Fagen, among three different roles: parts supplier, engineer, and builder. The engineer, the only person allowed to see the directions, first describes to the parts supplier which pieces are needed for the current step. Once the parts supplier finds and produces them, the engineer tells the builder where on the structure to place them. The kids assume a new job every 10 to 20 minutes, practicing the different communication skills that come with each as they build.

“The program has created a structure to building Legos, something that is not scary to these kids and forces them to use their social skills, and to improve their ability to communicate with each other in order to successfully complete the project,” Fagen explains.

The activity is not easy, but the builders have adapted to the challenge. “I notice things most people don’t,” says Blake, the 11-year-old Lego Club member.

Lego therapy isn’t unique to Franciscan, but the hospital has differentiated itself by accepting MassHealth insurance—a rarity, Fagen says, that will allow more families to utilize the group. “The vast majority of [social skills groups] are private pay, and the ones that aren’t private pay usually only take private insurances,” she says.

The program is still in its early stages, and has so far only served about 10 children. But by all accounts, it’s working. Fagen says a breakthrough moment happened when two kids had a full-on conversation without her help. The two boys who built the treehouse also reported improved description and cooperation skills during a mandatory reflection period. It’s those kind of advances, Fagen says, that help children on the autism spectrum truly start to grow.

“Ultimately, autism is a socially based disorder, so you can’t treat it in isolation,” Fagen says. “You need social skills in a group format, however that may be.”

If your child is on the autism spectrum and interested in joining Lego Club, contact Franciscan Children’s department of Behavioral Health Services at 617-254-3800, extension 3141. Find more information at franciscanchildrens.org.

Some of the Lego Club’s creations/Photo by Jamie Ducharme