Long-Lasting Pill Could Change the Way We Take Medication

Photo by Melanie Gonick/MIT

One of the shortcomings of oral medication is that it must be taken frequently. Taking a pill every day is often inconvenient, and forgetting a dose or ending a regimen early can compromise efficacy.

MIT and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) may have found a solution to that problem. The two institutions have developed a slow-release drug capsule that lasts two weeks—and, eventually, maybe even longer—in the stomach.

The capsule was tested for use in malaria prevention, but the researchers behind it say it could be used for virtually any condition that requires regular oral medication. That includes mental illnesses and Alzheimer’s—diseases for which forgetting a dose is a very real risk—according to MIT’s Robert Langer, a senior author of a paper about the innovation.

“Getting patients to take medicine day after day after day is really challenging,” adds lead author Andrew Bellinger, a former MIT post-doc and a cardiologist at BWH, in a statement. “If the medicine could be effective for a long period of time, you could radically improve the efficacy of your mass drug administration campaigns.”

Why can this capsule survive in the stomach while other pills can’t? It’s all in the design.

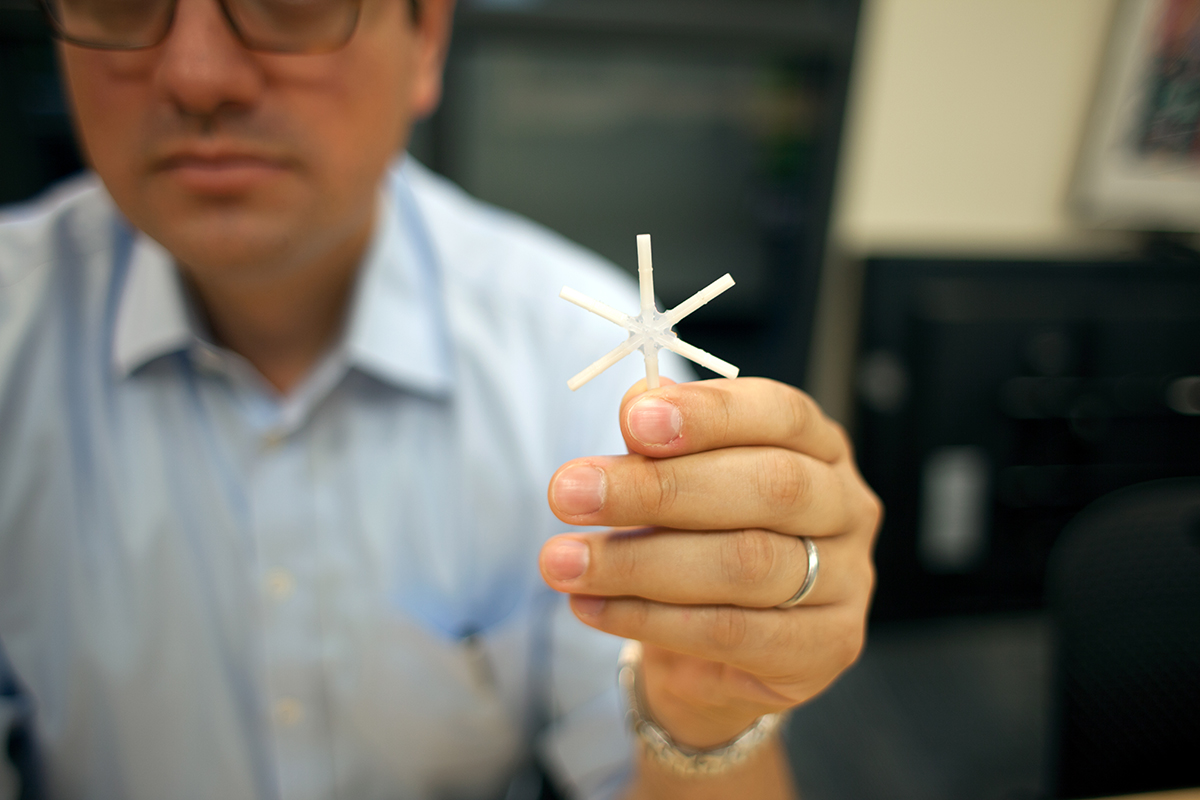

The research team developed a six-armed, star-shaped structure, each branch of which is coated with the desired drug. To allow for ingestion, the star structure folds in on itself and is encased in a capsule. When a patient swallows it, his or her stomach acid dissolves the outer shell, allowing the star to unfold and slowly dispense medication. The device’s large size allows it to remain in the harsh environment of the stomach for about 14 days, before partially dissolving and passing through the body.

The capsule was tested in pigs, with successful results. A mathematical model completed by the Imperial College of London also showed that, if used to target malaria in humans, the method would be significantly more effective than traditional treatments alone.

While your doctor can’t prescribe the capsules just yet, they may be on their way to market within the foreseeable future. Lyndra, a Cambridge-based company for which Bellinger is chief scientific officer, is getting the capsules ready to treat neuropsychiatric disorders, diabetes, HIV, epilepsy, and more.