Your Immune System May Play a Role in Alzheimer’s Disease

Though there’s a lot we don’t know about Alzheimer’s, researchers are getting closer to understanding its origins. Within the past year alone, the neurodegenerative disease has been linked to everything from brain asymmetry and concussions to diet soda consumption.

Now, a new study from Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) says your immune system may play a part, too. Mouse research suggests that blocking a molecule called complement C3, which is involved in the immune system’s cascade response to foreign pathogens, may help ward off the effects of Alzheimer’s disease.

Prior research has shown that C3 levels are elevated in Alzheimer’s patients. C3 is also part of the brain’s normal development process, during which unnecessary brain cell connections, called synapses, are trimmed back. Accelerated synapse loss is associated with Alzheimer’s and cognitive decline, so the BWH researchers hypothesized that lowering C3 levels could help slow that process.

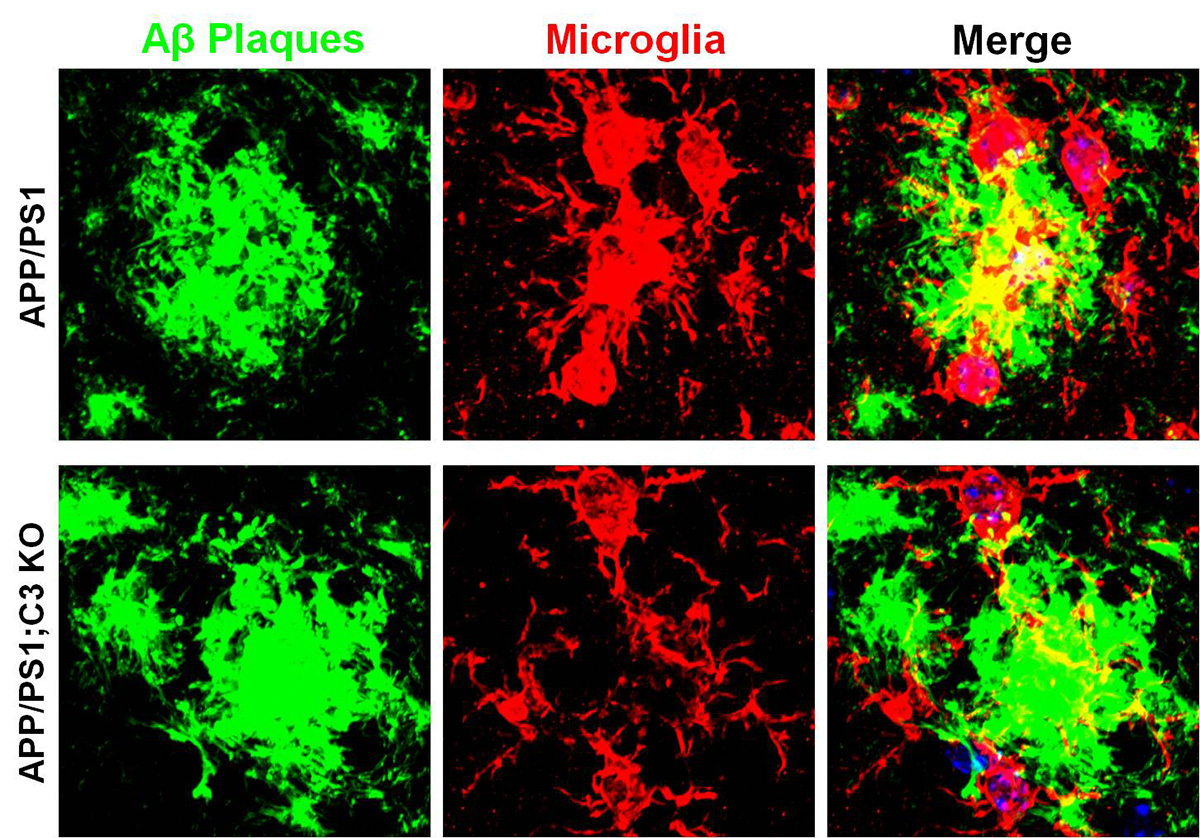

The researchers modified a group of mice to model Alzheimer’s, and to be deficient in C3. Compared to mice with normal C3 levels, the animals suffered less age-related synapse and brain cell loss, and had less inflammation in the brain. They still had many amyloid plaques—sticky protein deposits that build up around neurons—but, interestingly, they didn’t seem to impair memory and cognitive functioning as much as they normally do in Alzheimer’s patients.

The study was published Wednesday in Science Translational Medicine.

“Amyloid plaque deposition occurs years before memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease, but targeting how the immune system responds to these plaques could be an excellent therapeutic approach,” says corresponding author Cynthia Lemere, of the Ann Romney Center for Neurologic Diseases at BWH, in a statement. “We think that in later stages of the disease, it’s not necessarily the plaques but the immune system’s response to them that leads to neurodegeneration.”

While there are likely significant differences in how C3 deficiency affects mice and humans, BWH’s study provides an interesting new avenue for research moving forward.

Differences in the brains of mice (above) and C3-deficient mice (below)/Image courtesy of Lemere Lab at Brigham and Women’s Hospital