Local Researchers Mapped the Many Ways Cancer Cells Dodge Death

Image courtesy of Lauren Solomon/Broad Communications

Cancer cells are infuriatingly good at surviving when they shouldn’t. The nimble cells are able to adapt to a slew of mutations and molecular errors, persisting and spreading within the body as a result. The key to stopping them, then, may be understanding why and how they adapt so well.

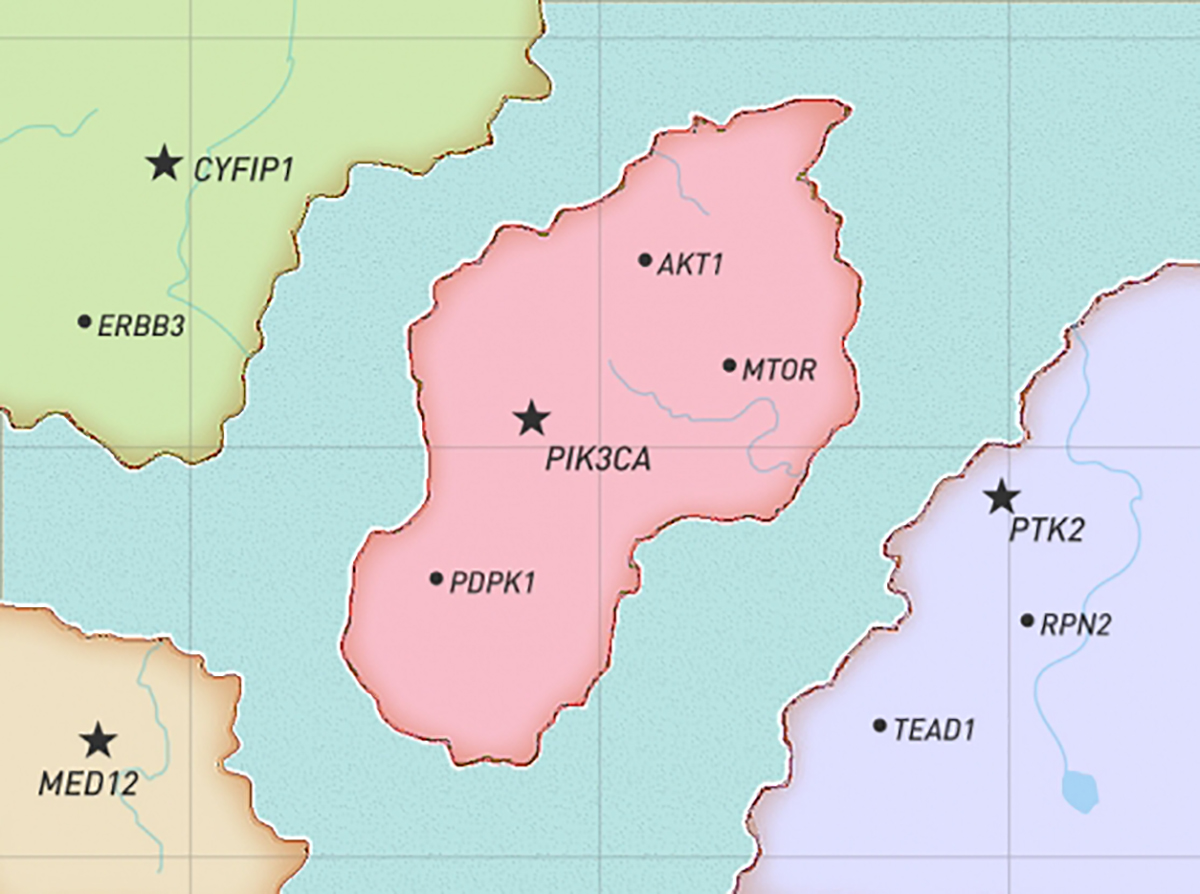

So a team of researchers from the Broad Institute and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) did something seemingly simple: They created a map. By plotting the many ways that cancer cells dodge death, doctors may be able to recognize the genetic crutches—adaptations that scientists call “dependencies”—that allow cancer cells to thrive in the body, and then develop treatments that target these weaknesses.

Of course, creating a cancer dependency map actually isn’t simple at all. The Broad has been working on one for 15 years, painstakingly screening thousands of genes and cells for clues. But in that decade and a half, researchers have been able to identify 769 dependencies—including gene mutations, under-expressed genes, over-expressed genes, or “reliance on a gene functionally or structurally related to another, lost gene”—that could someday lead to new cancer therapies. Those findings were published last week in Cell.

“Much of what has been and continues to be done to characterize cancer has been based on genetics and sequencing. That’s given us the parts list,” William Hahn, an institute member in the Broad Cancer Program and an oncologist at DFCI, says in a statement. “Mapping dependencies ascribes function to the parts and shows you how to reverse engineer the processes that underlie cancer.”

Some of the dependencies included on the map are cancer-specific, meaning they affect only some of the 501 cell lines included in the data set. But the vast majority—some 90 percent—could be traced back to a single set of 76 genes. That suggests a limited number of genes and pathways play a strong role in cancer formation and proliferation, and could be lucrative places to target treatment.

“We can’t say we’ve found everything, but we can say that the genes we’re seeing fall into a relatively small number of bins, some of which are familiar, some less so,” Hahn says in the statement. “That initial taxonomy is a great starting point for building a full map.”