The Case of the Patient Who Couldn’t Remember

A young patient suffered from symptoms similar to early-onset Alzheimer's. But Dr. Neel Madan of Tufts Medical Center knew better, imaging her spine for a leak instead.

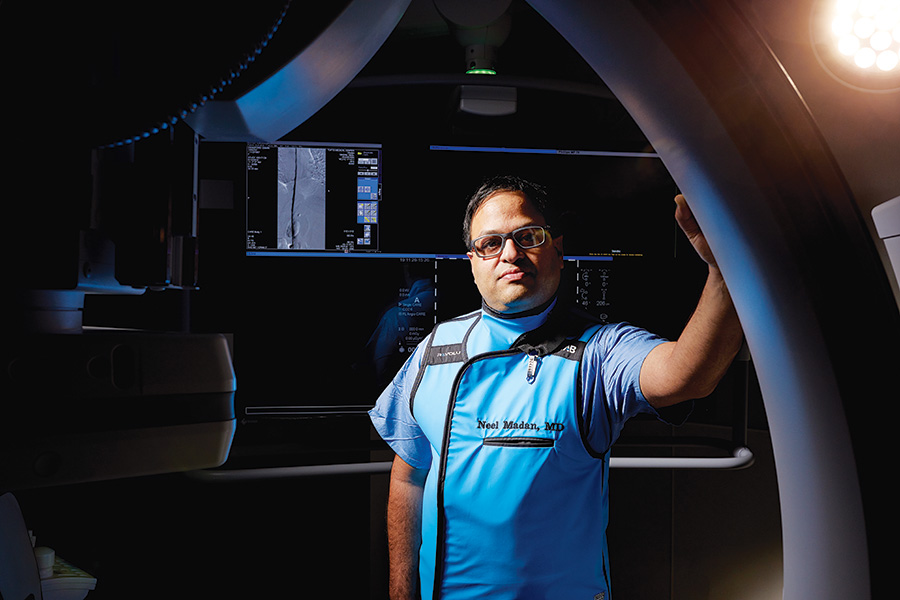

Radiologist Neel Madan, of Tufts Medical Center. / Photo by Ken Richardson

When Neel Madan’s wife came home from the hospital after giving birth to a baby girl and developed a splitting headache, he took her to the hospital right away. She’d had an epidural during the delivery, which can inadvertently create a small hole that causes spinal fluid to leak into the body. Madan, a Tufts Medical Center radiologist who is highly specialized in identifying just that, surmised that his wife needed an injection of blood in her spine to patch the hole and relieve her suffering.

Years later, when he first met his patient Sarah*, the case wasn’t nearly as black-and-white. The 52-year-old could barely remember family members, spent most of her day sleeping, and was fully dependent on others for almost everything—symptoms more in line with early-onset Alzheimer’s than a cerebrospinal fluid leak, which typically presents as positional headaches, brain fog, and difficulty concentrating. But after reviewing her medical history and imaging that showed low pressure and sagging in the brain, which is often indicative of fluid leakage, Madan agreed to take the case. When spinal-fluid leaks are caused by a puncture—like the epidural, in Madan’s wife’s case—they’re relatively simple to identify and fix. When the body spontaneously springs a leak, however, locating the hole is like finding a needle in a haystack.

If anyone could solve the mystery, though, it was Madan, who is trained in a highly specialized imaging technique called digital subtraction myelography. Typically, the procedure, which uses continuous X-rays with a dye contrast to systematically subtract tissue, helps Madan “clearly see where the fluids are pooling and that helps me know where to look for the leak.” But with Sarah, he says, he struggled to find it. He decided to inject 30 milliliters of blood into her spine anyway, hoping it would find its way to the leak and patch it up. The next day, Sarah was already recognizing faces and remembering names, and Madan considered the procedure a success.

Over the course of the next month, though, Sarah’s family noticed her cognition declining. The blood injection had not fixed her. Eager to find the leak once and for all, Madan asked Sarah to come back for another test, only this time he had her rest on her side rather than on her abdomen, hoping that moving her body would help the dye contrast pool differently and lead him to the source of the problem. And it did, revealing that Sarah had a rare spine condition called a CSF venous fistula. This leak occurs at the connection between a nerve root and a spinal vein, which is why it had been so hard to find.

After Carl Heilman, Tufts’ chief of neurosurgery, repaired the leak, Sarah’s dementia essentially disappeared into thin air. In fact, within four days, she was more aware and getting back to her old self. She is still doing well today. “It was important to continue to look for a potential leak,” Madan says now, “and not just stop after the first test.”

*Name has been changed.