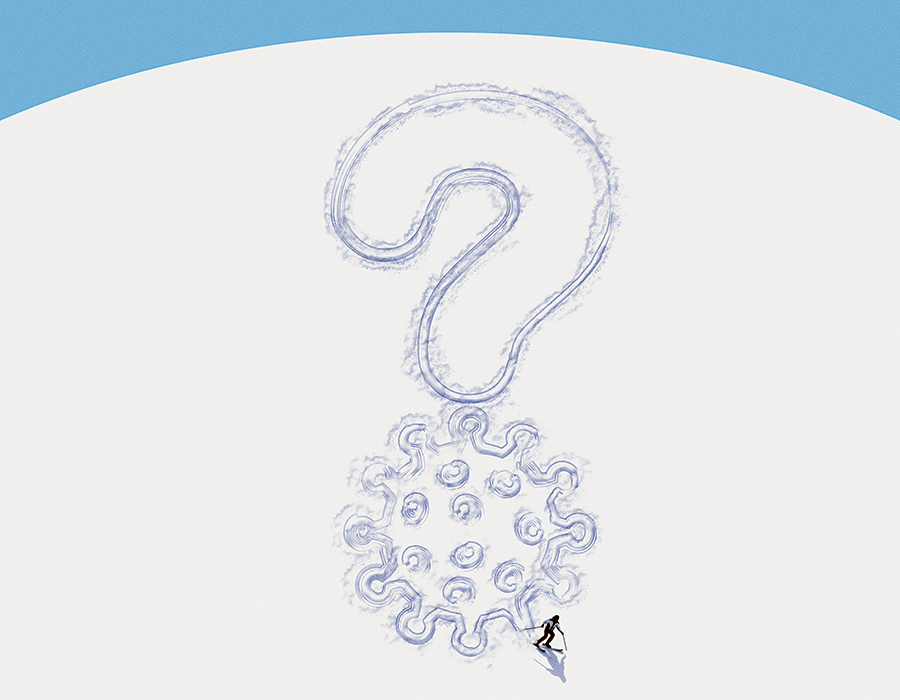

COVID vs. the Ski Industry

With all of us looking for things to do outside this winter, could the pandemic actually be the best thing to happen to local mountains since snowmaking in April—or are New England’s already-fragile ski resorts heading for a wipeout?

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis / Skiier image via Getty Images

The morning of March 12 at Jay Peak ski resort in Vermont’s Green Mountains, was, by all accounts, a bluebird day. That’s old-school, ski-bum speak for bright blue skies after a night of snowfall. Yet inside the boardroom at the Hotel Jay, the mood among the executive team—outfitted in down puffers and all-weather boots—was anything but sunny.

It was 8 a.m., and everyone was talking about the emerging pandemic. The question was not what to do but when. Jay Peak had already enjoyed a great snow season and was on track to host more families that season than any in the past, and there was probably still a good month and a half to go before the mountain closed. It was spring break in Ontario during the coming week, one of the biggest income generators for the resort, which lies just 5 miles south of the Canadian border. To JJ Toland, the mountain’s communications director, the idea of shutting down in mid-March felt like a punch to the gut. He knew it would mean hundreds of thousands of dollars in refunds and more than 1,700 employees instantly being out of work. But as the meeting wore on, it became increasingly difficult to ignore the writing on the wall. Schools around the country had begun to send kids home. The NBA and the NHL had suspended their seasons. Offices were closing. At 10 a.m., as smiling guests piled onto the tram outside the trailer to make their first runs in fresh snow, the team made the call: Sunday would be it; the 2019 to 2020 ski season was over.

It was an almost unthinkable turn of events for an industry already suffering from a multitude of woes, from climate change and waning interest in the sport itself to rising operating costs and shrinking margins. In the past decade alone, skier visits to mountains dropped by 15 percent nationally, and over the past two decades, nearly 30 mountains have shut down across the country. Even with the increasing price of lift tickets, profit margins have gotten dangerously low, with one industry expert putting the average profit per ticket—before taxes—at $7.34.

By the time Sunday rolled around, three days after the Hotel Jay meeting, much of the American ski industry had followed Jay Peak’s lead and ceased operations. The impact was devastating from East to West. For Vail Resorts, which owns 34 ski properties across the country, including Okemo and Stowe mountains in Vermont, the early closure resulted in a $205 million loss compared to the year before. For the local economies of ski towns, it meant losses of untold millions. Some mountains did not survive. When Ski Blandford, a small slope in western Massachusetts, closed in March due to the pandemic, it announced it would never reopen.

Now, some eight months later, with winter fast coming and no end in sight to COVID-19, the ski industry is approaching the upcoming season with cautious optimism. Many of us have recently rekindled a love for the outdoors, and any pastime that can be enjoyed at a prudent social distance has the potential to set up resorts for something of a resurgence that could last well beyond the pandemic. Indeed, says Adrienne Saia Isaac, director of marketing and communications for the National Ski Areas Association, “This could be a season of opportunity.”

For all of the industries that have suffered devastating blows during the pandemic, there are a handful for which it has been a full-blown boom. Recreational activities are foremost among them. Bicycle sales, for instance, have skyrocketed: “They’re buying bikes like toilet paper,” one industry analyst told the Chicago Tribune in June, citing numbers that hadn’t spiked so high since the oil crisis of the 1970s. Outdoor-furniture sales and waitlists for firepits and inflatable pools grew as many settled into summer homes, while the RV rental market soared among those who just couldn’t stay put. While warm-weather group sports such as softball and organized runs took a hit, individual and family-oriented outdoor activities exploded. According to the Outdoor Industry Association, cycling, hiking, and running made the biggest gains among first-timers in particular, with participation some 8.4 percent higher than during the same period in 2019.

This arguably bodes well for skiing. In fact, there are already some promising signs. By early September, retailers such as the Ski Monster in Boston were starting to see early customers—who may have learned the lessons of the great bike shortage—line up for gear fittings. Rhode Islander Dave Mongeau bought new skis for the first time in 25 years. “I’ve been going skiing sporadically with the kids maybe twice a year,” he says. “But this year, I’m looking at winter so differently.” His younger son, a high school senior, attends in-person classes three days a week, which leaves the possibility of heading off for long weekends to enjoy the family’s even bigger pandemic purchase: a house in Vermont.

Mongeau wasn’t the only one snatching up mountain real estate. Adam Palmiter, a Realtor in Vermont’s Mount Snow area, says demand is so high and inventory is so low that he finds himself telling dozens of callers a day that he has nothing to show them. “If you are a buyer, you can’t act fast enough,” he says, telling me that he could double his sales numbers from last year and possibly set a new Vermont Realtor record. “I’ve heard that six months of COVID will undo years of population decline in Vermont.”

Meanwhile, Sunday River sold nearly half of its condos in a new development in less than two weeks, even though construction won’t be completed until 2022. By late August, when hot days and humid nights blanketed New England, Jay Peak had already sold a handful of $15,000 “Relocation Vacation” packages that include four season passes and 159 days in a private cottage.

Things are equally hot in the rental market. Dorchester couple Leslie and Brian MacKinnon typically book houses through Airbnb or Vrbo to ski with their two kids and family friends twice a season—at Bretton Woods in New Hampshire and Sunday River in recent years. This year, with both kids learning remotely, they considered renting a place for four weeks or more. By the time they began looking in late August, though, they realized everyone else had the same idea. “My friend just sent me a house near Stowe that was $1,000 a night,” Leslie says. “I was like, if we want to do that for four weeks, that’s basically a down payment. We might as well just buy a place.” She’s only sort of joking, while also recognizing that they’re unlikely to find anything affordable to buy, either. “We keep being told there’s zero inventory, and what does come up gets scooped up, same day, sight unseen, by New Yorkers paying cash,” she says. “I’m not feeling optimistic we’re going to find anything at all.”

In many ways, skiing and COVID make perfect bedfellows. There’s the bulky equipment and layers of gear that provide a buffer of protection, including goggles, which do a better job than a face shield of protecting the eyes from errant respiratory droplets; and the gaiter, which has become a popular and effective way to cover the mouth and nose. Plus, there’s only so close you can get to another skier without crashing into them out on the slopes or in the lift line. The pivot to work—and school—from home, meanwhile, has allowed for a flexibility most families have never known. “Resorts have been trying for years to get people to ski midweek,” says Dave Belin of RRC Associates, a Boulder, Colorado–based market research firm that covers the ski industry, “and all it took was a global pandemic.”

During a late-September call to shareholders, the CEO of Vail Resorts reported that season-pass sales were up 18 percent over the same period last year. The amount of money brought in was down 4 percent, but that’s factoring in the credits Vail gave last year’s passholders for portions of their unused purchase. “So when you remove that, dollars are actually up 24 percent,” says Paul Golding, a senior research analyst at Macquarie Group. “Which is surprisingly very positive.” Golding predicts that “destination” mountains, many of which are out west, may have a harder time making up losses due to the fact that some skiers may not be willing to fly there. Conversely, mountains with an abundance of urban markets within driving distance to draw from—which is most mountains in New England—may in fact struggle to keep their numbers down.

The inherent expense of skiing—few lift tickets go for under $100 a day, plus there’s all that gear—means it’s not a sport for everyone, of course, but it also means it’s a sport with relative staying power. Once you invest, whether it’s in a pair of $700 skis or a $700,000 condo, you’re likely to want to make use of that investment, year after year (the same may not be said of all those inflatable pools). That means whatever gains the industry sees this season are likely to last well into the future. The COVID bump in skiing may just be the gift to the industry that keeps on giving.

None of this is to say that skiing this year will look like we remember it. Following guidelines issued by the state of Vermont, Jay Peak created a preliminary plan that includes mandatory masks in all public spaces (indoor and outdoor), capacity restrictions on the tram to the peak, and reduced seating at restaurants and bars, all outlined in a living document that will continue to be updated and refined as winter approaches.

Vail Resorts’ plans for the 2020 to 2021 season, meanwhile, include advance reservation requirements for all skiers, with priority given to Epic passholders. Sunday River announced it would not require passholders to make reservations, but everyone else will be encouraged, and possibly required, to purchase lift tickets in advance.

Whether mountains will require reservations is so far one of the trickiest points in the new skiing normal. Many mountains are reluctant to discourage potential guests, and many guests are put off by the idea of having to plan ahead in a region with unpredictable weather. While larger resorts such as Sunday River, which can accommodate 29,000 skiers, may never reach capacity—aside from, perhaps, during peak times such as Christmas week or Martin Luther King weekend—smaller, day-trip mountains trying to allow for a bit of spontaneity may need to get creative. Wachusett, whose guests are almost entirely day-trippers, is considering selling tickets for four-hour sessions instead of full-day passes in order to spread out demand. “That’s also where smaller mountains have more to gain,” Belin says. “If we start to see big crowds at, say, Sunday River or Sugarloaf, that’s great news for them—but it’s even better news for a smaller place like Saddleback.”

All of this, however, may as well be written in snow. At press time, two months before mountains are expected to open, plans were shifting rapidly and many scenarios may need to be scrapped altogether once skiers actually arrive. As Jay Peak’s Toland says, “There’s no doubt that the winter of 2021 will be playing hide-and-seek with reality. Anyone who tells you they have a fair handle on what it’s going to look like is playing with a hubris grenade. Because it could, you know, turn on a dime.”

Even if it all goes off as planned, you can pretty much bid adieu to après-ski, at least as we know it. There will be no more sweaty, beer-soaked live-music scenes and zero packed hot tubs. Instead, we’ll get more outdoor seating at dining and drinking establishments, more to-go options, and, in many cases, order-by-phone capabilities. “We’re bringing back skiing to the way it used to be,” says Kris Blomback, general manager of Pats Peak in Henniker, New Hampshire. “When I grew up skiing, my parents and I would boot up in the car, bring a picnic lunch, and use our big old ’72 station wagon as a base lodge. I think it’s going to be a bit like that, except now with technology, if you want to bring a pizza back to the car or to one of the many outdoor seating areas we’re establishing, you can.”

Some resorts could attack their shrinking margins with an increase in ticket prices. Belin says he anticipates that this year there will be an increase in prices above the usual annual 4 to 5 percent. Other mountains may reduce their operating expenses by postponing lift upgrades and opening fewer trails to help reduce snowmaking costs. Terrain parks, full of manmade snow obstacles, are particularly expensive to make, says Belin, adding that a mountain that used to have four might have one this year. “The mountains that will thrive will be the ones that are cautious about preserving their cash and putting off capital improvements,” he says. “And that may require skiers to exercise a level of patience and understanding.”

Will they? It’s hard to know. This has been a long stretch, and people’s tolerance for life under COVID is wearing thin. And yet, Golding says, the one thing no one’s preparing for is the one thing no one can ever prepare for: how much snow we’ll even get. The Farmers’ Almanac says winter looks “cold and snowy.” But analysts don’t count on weather predictions, especially in New England. “That,” Golding says, “would be crazy.”