This Is How a Concussion Blood Test Works

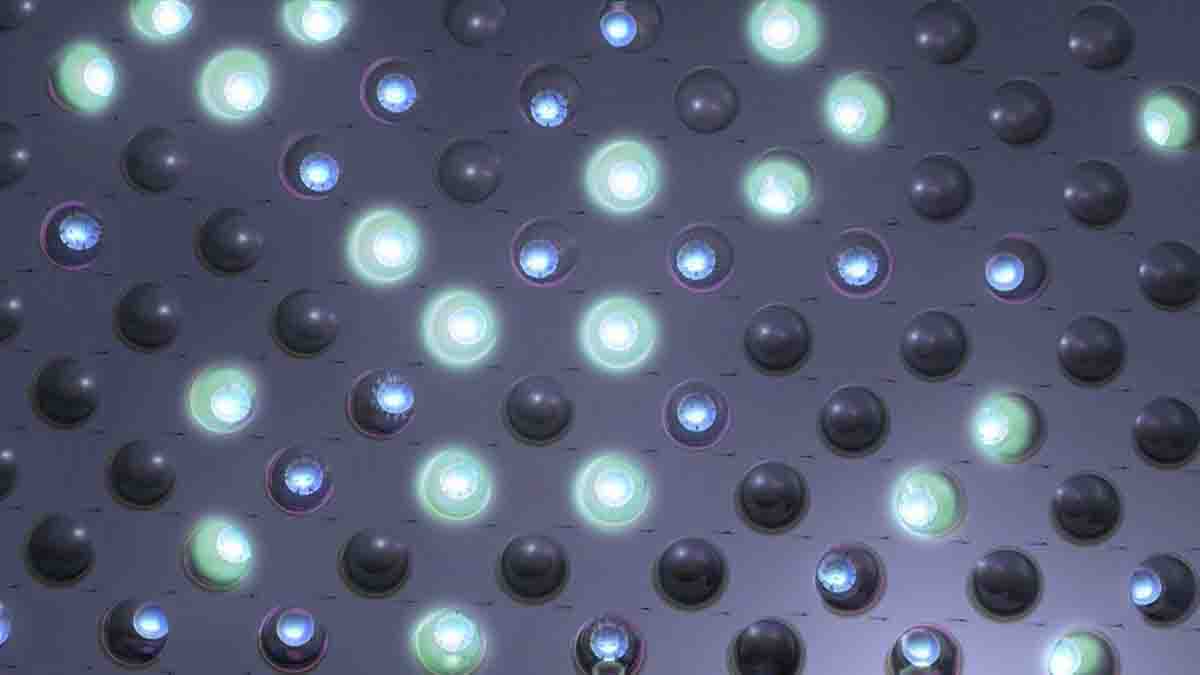

An illustration of Qunaterix’s technology, provided.

Lexington-based Quanterix has been in the news lately for its concussion-detecting blood test, a technology that has grabbed the attention of organizations including the NFL.

But how does a concussion blood test work? We spoke with Kevin Hrusovsky, CEO of Quanterix, to find out.

How does the technology work?

Quanterix’s Simoa 2.0 system contains 500,000 tiny beads, covered in antibodies that attract specific proteins, and other antibodies that light up in the presence of those proteins. When the beads are put into a blood sample, they light up in the presence of the protein in question. Then, the beads are placed on a matrix covered in tiny wells. From there, a camera examines each well to discover if any of the beads are illuminated.

Okay, so what does that have to do with concussions?

“When someone has a concussion, the brain releases critical proteins into the cerebral spinal fluid, and some of that leaks across into the blood,” Hrusovsky explains. The Simoa 2.0 can test for those proteins in less than an hour, accurately determining whether the individual has had a concussion.

Why is this better than other diagnostic methods?

In short: It’s objective and it’s accurate, says Hrusovsky. “We can see things in the blood that nobody thought was possible,” he says. “Our technology would be capable of finding a grain of sand in 2,000 Olympic swimming pools.” Beyond that, the system takes out any doubt or judgment calls from the process.

At the moment, concussions are something of an epidemic in the United States—and CTE, a disease associated with concussion-induced brain damage, was just given its own diagnosis—so that kind of accuracy could change the way they’re treated.

What else can the system be used for?

In addition to concussions, Hrusovsky says Simoa can test for a protein present in heart disease sufferers, and biomarkers that suggest a cancer remission. “Because our technology is so sensitive, we can see the cancer coming back six to nine months earlier than imaging technology can,” he explains. “Being able to see this stuff objectively, in blood, I think, is a really big piece of the future of medicine.”

Who’s using it?

Right now, mostly neurologists, neurosurgeons, and pharmaceutical and biotech companies. Hrusovsky says diagnostic companies may be next.