Gray Matters: Why I’m Saying Goodbye to Dye and Embracing Gray Hair

Saying goodbye to dye was the best breakup of my life.

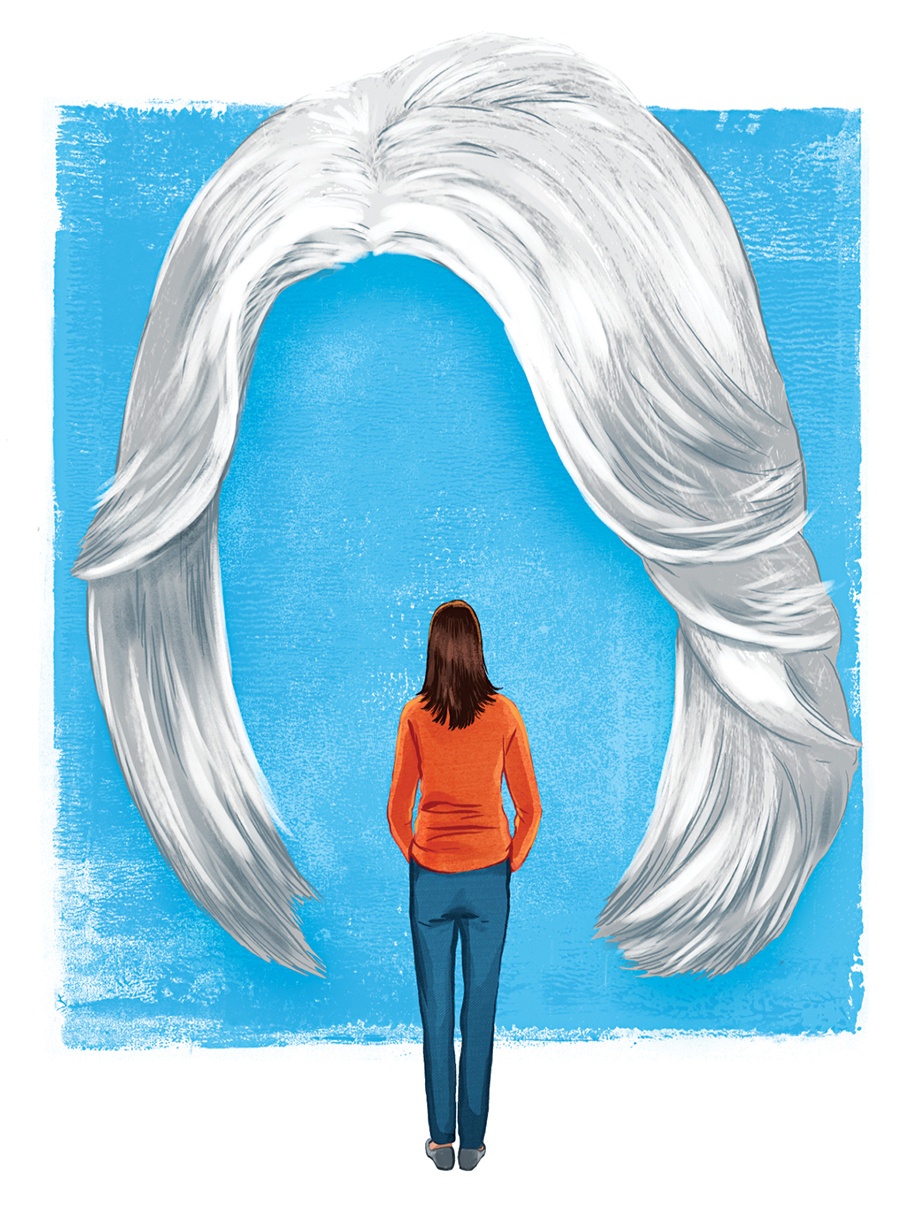

Illustration by Rob Dobbi

Gray is a misnomer. There’s literally nothing on my head that qualifies as gray. There’s every shade of brown (some of it homegrown), and then there’s white. Maybe we use the word “gray” to soften the aging blow, as if there’s some kind of graceful middle zone between youthful and elderly, but the hairs emerging from above my temples and scattered in and around the brown are not equivocating. They are white. Aggressively white. Unabashedly white. The very idea that they were once brown seems absurd.

After years of fighting these bad boys, I’m finally welcoming them in—the final act in nearly half a century’s worth of mane struggles. “Ask a woman about her hair, and she just might tell you the story of her life,” Elizabeth Benedict writes in Me, My Hair, and I: Twenty-seven Women Untangle an Obsession. I’ll spare you the life, but I will give you an abbreviated version of my hair story.

I was always brown hair, brown eyes. That’s what it’s said on my driver’s license since the day I got it 32 years ago. Brown on brown, just like so much of the world’s population. The blandness of the palette I’d been given was all the more apparent to me because my mother had a head of brilliant red (which she never, ever dyed) and green eyes that forecast her state of mind like a supercharged mood ring. Red hair could be a liability—she freckled at the thought of the sun and it was the cherry-on-top zinger against ugly stepchildren—but to me as a little girl, the hue was an extravagant gift. Even now when I see redheads, I can’t resist letting them know that I have a one-degree separation from such a rare and dazzling genetic glitch.

My hair, in contrast, was exactly what the dye industry was designed to correct, and I had bottomless faith in ad copy that promised fabulous head-turning transformations. My first attempt took place during junior high in a friend’s bedroom where we spent an entire evening spraying a bottle’s worth of Sun In into my hair and attempting to use the heat of a blow dryer to turn it blond. (No dice.) In college, I bought bottles off drugstore shelves and destroyed at least four sinks going from eggplant to ebony to mulled wine, then a hue of orange so horrifying that a stranger on the subway advised me to cut it off.

In my late twenties and thirties, I had enough money to hire professionals, and that’s when the salon chair became the site of a thousand miracles. Modern alchemists keep their magical powders on salon shelves; mixed with water, poured into a plastic cup, and coated onto locks, dye unleashes its otherworldly power in under three hours. Unhappy? Vaguely dissatisfied? Intermittent golden, amber, or crimson highlights could fill every emotional void, at least until rain or humidity sent my languid locks into a frizzy frenzy.

Like countless women before me, I was 40 years old when I first started to see the white stuff creep around my crown, which put my heretofore solidly brunette identity on notice. What I had always been—brown hair, brown eyes—had become a fragile condition. Something I’d have to fight for. Each white hair inching out was a warning shot across the bow from my future self—a flag, a flare, a public service announcement—telling me that I’d lived on this planet for so long that my follicles were over it. They were all heading for the same retirement community in Florida. I knew from vast experience that they could be dyed, but I was still in Boston, trying to freeze time.

After a few years of dyeing, I’d occasionally ask various stylists whether I should just give in to gray. “You’re too young for that,” they’d tell me. (Compelling evidence to the contrary: I didn’t recognize any of the young celebs featured in the salon’s gossip mags, which I could only read using my exorbitantly expensive progressive lenses.)

For a long time, I wanted to believe my hair team, though. I knew that telling the truth on their part presented a certain conflict of interest, but then again, whenever I exited the salon with my shiny mane of fresh cocoa and copper hues glistening in the sunlight, I felt pricey, coifed, and coveted—utterly perfect, like a late-model Bentley with leather seats, a walnut steering wheel, and a bar in the back with custom crystal glasses carved with my initials. That light-purple stain on my forehead next to the hairline was a luxury tax.

By my mid-forties, though, I was scheduling my life around regular six-week dye jobs and home touch-ups in between. If I delayed for even a couple of days, that silver halo forming at the temples became a mortification, like discovering the sweater you wore all day still had the price tag on it or a dribble of coffee down the front. And because it became a chore along the lines of doing dishes and getting mammograms, I started enjoying coloring less and less. Yes, I wanted to look an indeterminate age, somewhere between 38 and 52. But every time I painted on the brown, I felt a little clownish. These dye jobs had become acts of desperation.

Then one day late last October, I got home from the salon, looked in the mirror, and saw Marilyn Manson staring back at me. His hair was a solid mass of darkness. He was sallower than usual, with hints of green in his translucent complexion. He appeared undead, but without the heavy-metal charm. In short, Marilyn Manson needed help.

I stood there for a while trying to reconcile a paradoxical condition: My hair was stunning as always, thick and luscious chocolate. But it looked like I’d swiped it off a twentysomething.

That’s how I knew the ruse was up. An alarm clock set precisely 48 years ago had gone off while I was sitting in that salon chair, and suddenly, I was too old for this.

Part of aging is accepting reality and gracefully rolling with it; I’d always wanted to be that woman whose elegance transcends her years. But when you’re in your mid-forties, still trying to figure out what you want to do when you grow up, and the whites suddenly appear on the scene, theory and practice collide. I was wholly unprepared to deal with this new variable.

Up to that point, I’d spent decades of mirror time trying to figure out how to enhance the stuff I’d been given. All that energy spent finding my ideal self—the perfect haircut, the right hues, highlights, lowlights, balayage, Brazilian blowouts—now seemed quaint. I’d reached the peak without even knowing it and I was slipping and sliding down the other side. I’d spent years sweating over all the little details and now nature had thrown down the gauntlet, forcing me to chart a new course called preservation.

The men around me went craggy, bald, and paunchy, assuming a “rugged” look that gave them an air of weathered respectability. Their burgeoning guts wielded a certain kind of masculine power. But to my American-trained eye, any lapse in physical care on the female part was an admission of something, a kind of “Fuck you.” Girls and young women drain so much of their immense energy on preening, avoiding doughnuts, accessorizing, and generally casting a relentlessly critical eye on themselves that they inadvertently cede the arena to men. We get up earlier, go to bed later, and spend much of our personal fortune on beautification.

When we stop, if we stop, we find ourselves with a lot more time to get things done. That puts us on equal footing, but the message comes with a price. We don’t look our peacocking best. But I ask, is letting go the same as giving up? Or is it flipping the bird to the double standard, at last, and just being you?

In an attempt to glean some clue about how changing my look might change how I felt, I turned to the fount of all wisdom: the Internet. My search (workshopped to dodge references to a certain S & M bestseller/trash movie series) led me to Pinterest, the site of all my visual revelations.

That’s where I learned that I was seeking to “transition.” I learned that there were indeed 50 shades of gray, from gunmetal to pearl to smoky to oyster. I learned that silver was considered hot, especially when executed on women born after 1995 (not helpful). I created a private board called “Going Gray,” which I filled with inspirational photos of other heads, other hair, other hues.

I also started noticing Boston women of a certain age around the city. Some had gone blond to hide the whites. Some just quit the dye altogether and waited with the patience of a Galápagos turtle for the natural color to grow in. Some were like my mother—who was now a kind of pinkish shade of white—and had never touched dye in the first place. I envied them.

I knew I couldn’t handle an eternal grow-out period; I’d shave it all off before tolerating a look that suggested abdication. So, I went back to the only place that could save me: the salon chair. Patty Martin, of Love and Mercy Salon, had done my color before. I stalked her Instagram feed before calling, in search of women like me. I didn’t find any. Could Patty handle the problem I was throwing her way: the quest to go gray without the waiting period? To me, it seemed like an outrageous demand. But I couldn’t stand to go another day—my dyed shield against time’s arrow was suddenly holding me back.

A few weeks after the start of my search, I finally found myself sitting in Patty’s chair, watching her in the mirror as she parted my hair this way and that, trying to understand how far my follicles had journeyed. The Marilyn Manson dye job had already begun to dull out. The whites were muscling their way back. I looked appalling.

“Okay,” she said after five minutes of close scalp examination. “We’re going to take out all this red and go to ash tones so that the overall color blends better with your natural color. And we’re going to pull through some charcoal highlights to frame your face where your natural grays are strongest.” And then, the punch line: “I want you to grow it out for another month before we do this.”

I made an appointment and waited a few geological ages for our date, stealing looks at my Pinterest board at every opportunity, anxiously wondering whether this costly transformation would hurl me square into middle age. Then, on a frigid day in January, just after the New Year, I abandoned the woman I thought I’d always be.

Patty spent eight hours color-correcting and highlighting. She didn’t like some reddish hues coming out and sent me back to contemplate another stack of magazines, my hair wrapped in tinfoil sheets like so many sticks of Wrigley’s gum. I began to feel like a permanent fixture in her salon; I sipped coffee and made up backstories about the other people getting their hair done. It was the longest I’d ever spent in a chair. Finally, after the sun set, turning the salon windows into giant black mirrors, Patty washed and dried my hair and released me.

Yes, the overall tone was ashier, which definitely worked better with my fortysomething face. And to my delight, the new streaks of charcoal—bleached out and then toned—had hints of blue. Not quite enough to be punk rock, but enough that I looked like I’d taken charge of a serious hair problem in the most mature of ways: ironic celebration. I was the blue-haired old lady and I was rocking it.

I haven’t touched the color since. The whites are growing in but now look at home nestled among the blues, charcoals, and ashy browns. I kind of love studying their growth in the mirror, finally free to cheer on those whites instead of eradicating them. They are truth, my truth, and they fit into the bigger picture, which is that in a short time I’m going to turn 50.

And as if to prove how little we actually understand about the universe, after jump-starting my transition, I started getting thumbs-up from friends and strangers more than ever before. Random people seemed friendlier to me. I received unsolicited compliments from colleagues, smiles at Whole Foods, and even a few obvious pickup attempts by not unattractive (albeit age-appropriate) strangers.

So now I’m rooting for those little white hairs; I’m coaxing them out of hiding. I’m going full-on silver-back and loving the freedom that comes with embracing what nature handed me. In fact, for what may be the first time in my adult life, I’m kind of thrilled to see the real me.

I understand the fear that comes with change we can’t control. But there’s also something merciful about how age transforms our appearance. Grays signal to others that we’ve been around for a while and have the wisdom that comes with that—the wisdom to bend, not break. The wisdom to choose which conventions matter and which are simply ridiculous. I’m not the little old guru on the mountain yet. But at least my mellower, more liberated, infinitely wiser inner self finally matches my hair color.